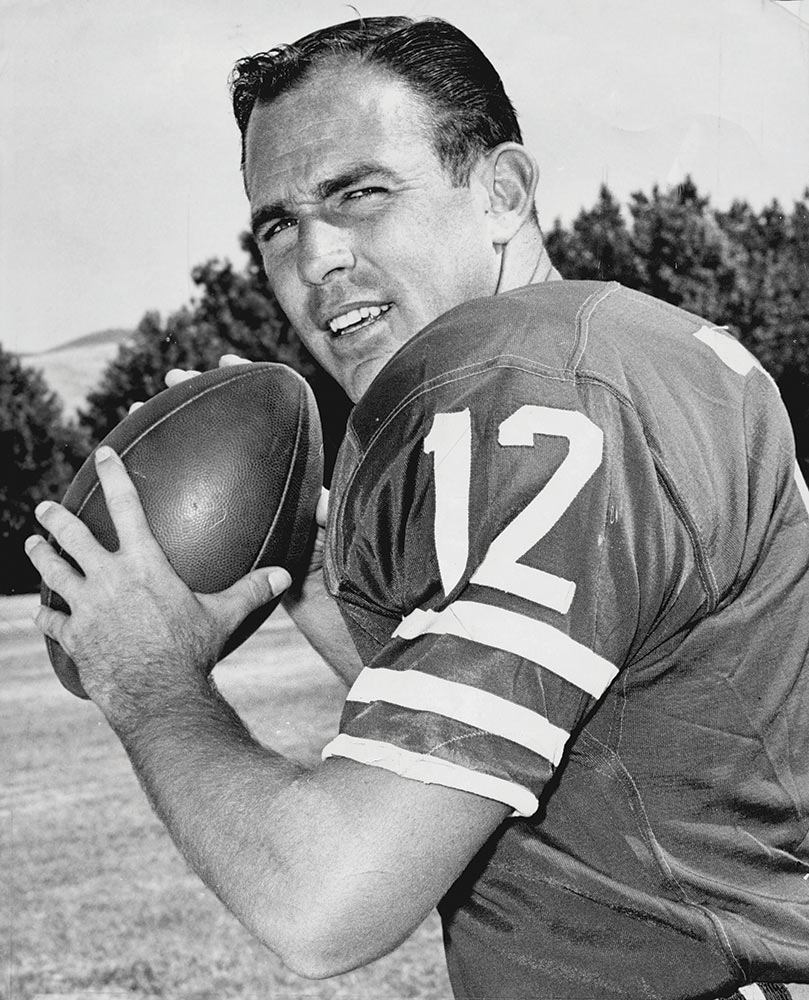

If he had played quarterback for a different team or if he hadn’t found the water on the 15th hole of a 1960 tour event, John Brodie’s path might have led to “legend.” Still, as Art Spander writes, “Great” works well enough for the man born with astonishing athletic ability

Oh, what might have been.

The saddest words? Not for John Riley Brodie, whose solid accomplishments belied his even greater possibilities.

Athletically, Brodie simply was too good at too many things, a natural.

He could play. Anything. And he did play: was being a star in basketball and baseball at Oakland Tech High, before ending up a great NFL quarterback and champion senior golfer, enough for one man?

But still, what might have been. Go back years and years ago, to January 1960, and only a month after Brodie, in his third season with the franchise, had been playing backup quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers. But now, instead of throwing passes at Kezar Stadium—the windblown facility a couple miles inland from the Pacific and once the 49ers’ home field—he was on the 15th fairway at the Yorba Linda Open in southern California, two strokes ahead of Arnold Palmer, four behind Jerry Barber.

After a solid tee shot on the par-5 hole, Brodie, a gambler—on the course and off, a bold individual who always played to win—went for the green in two, but the ball plopped into a pond and a double bogey ended his chances. Ultimately he would finish 10 back of Barber, and in effect ended any thoughts of a career change.

“I always wonder what would have happened if I knocked that ball on the green and holed it and won the tournament,” said Brodie, reviewing his life and sounding like so many golfers pro or amateur. Would he have quit football and gone on Tour full time?

Brodie would play occasionally as a pro before regaining his amateur status, and then in the late 1980s, after he left the NFL and was working as an announcer for NBC on both football and golf, he followed his muse and joined the PGA Senior Tour. This was long before it was renamed the “Champions Tour.”

Brodie did become a champion, not that he already wasn’t one, with his previous success coming in 1970, partnering fellow Stanford University alum and full-time tour pro Bob Rosburg to a team victory in the in the Bing Crosby National Pro-Am, now the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am. (“If I had John’s game I think I would have won the pro tournament,” was Rosburg’s assessment.)

But it was in 1991, at the age of 56, that Brodie gained genuine golfing recognition, beating George Archer and Chi Chi Rodriguez in a playoff at the Security Pacific Senior Classic and becoming the first athlete from another sport to win on the Champions Tour.

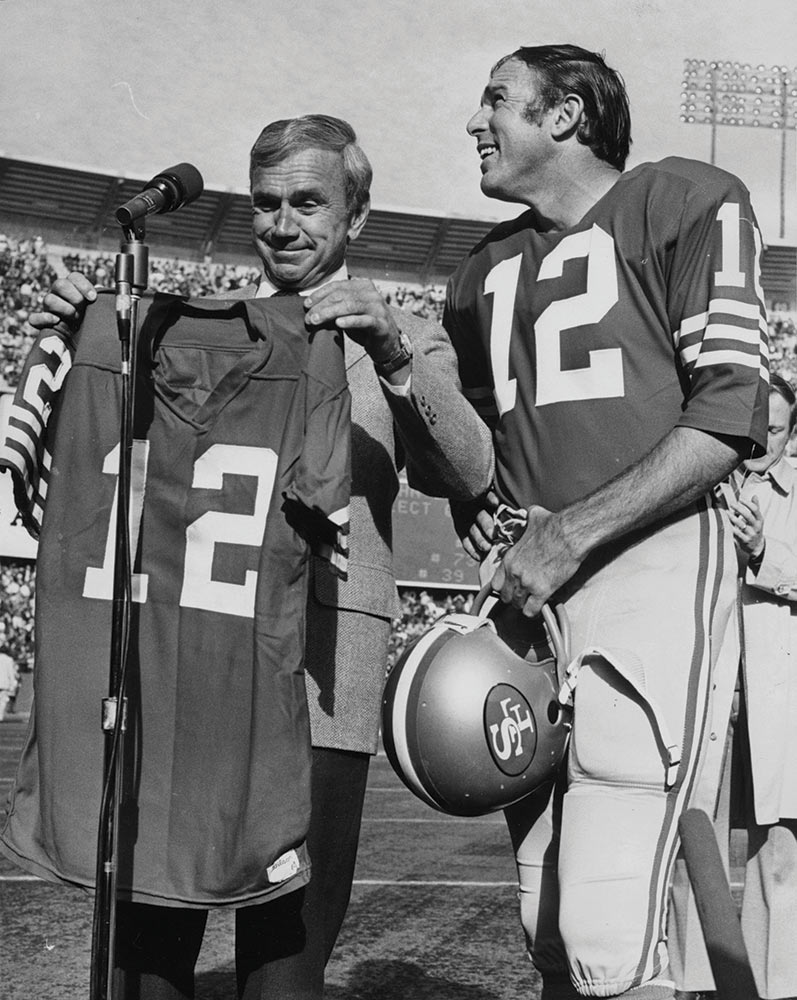

Unfortunately, the man who at 17 years with the team remains the longest tenured player in 49ers history, who was so skilled at sports and has a beautiful wife, family and wealth—so blessed in life—suffered a debilitating stroke in October 2000. He would survive, thanks to doctors at the Eisenhower Medical Center in Palm Desert, California, but he was unable to play golf and was barely able to talk. After months of therapy, Brodie made progress with his speech. Such a cruel twist to the story of a man who is now 83 years old.

During the week of the 2012 U.S. Open at San Francisco’s Olympic Club, a course Brodie knew well, he was transported to Lincoln Muni, overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge, for a television interview. There in a setting and among people he knew, and aided by daughter Cammie, Brodie managed a few words and a few smiles but you sensed he wished to leap from his wheelchair and take a swing with a 5 iron.

So much had been in Brodie’s favor, besides his natural skill. At Stanford, the school of Tiger Woods, Tom Watson, Sandy Tatum, Charlie Seaver, Lawson Little, and others, Brodie could play one of the finer courses in the country. After joining the NFL, he honed his golf against Tony Lema, Ken Venturi and Rosburg, all major champions and all from Northern California as well.

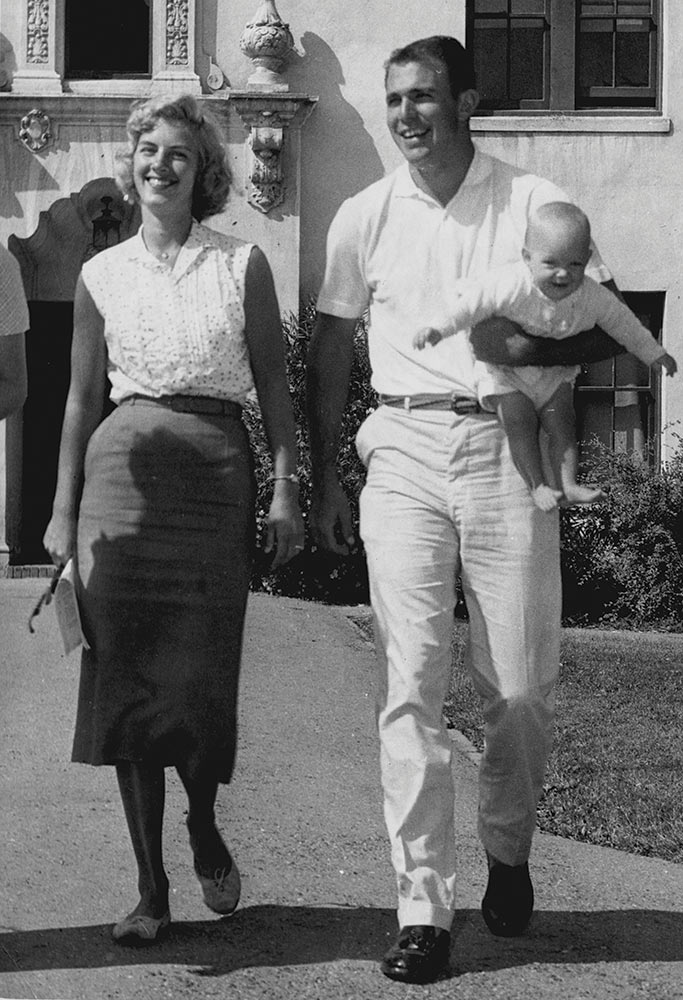

Brodie craved competition—he even played in the World Dominoes Championship. The Saturday Evening Post dispatched writer Herbert Wilner to do a profile on Brodie early in his NFL career: “John Brodie,” wrote Wilner, “is a man at ease, and the ease has a style: A California aura of sun, satisfaction and winner-take-all.”

As Brian Murphy, writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, penned in 2004, “Nobody wanted a piece of [John] in a game of cards. Same with bowling. Or ping-pong.” Tennis, golf… It was all the same, and if the stakes weren’t high enough, Brodie figured there was no reason to play or wager. “I’ve never seen a guy who could play more games well than John,” observed Rosburg (1959 PGA Championship winner) in the Chronicle article. “If somebody said, ‘Let’s have a decathlon of different sports or games,’ he might have won it all.”

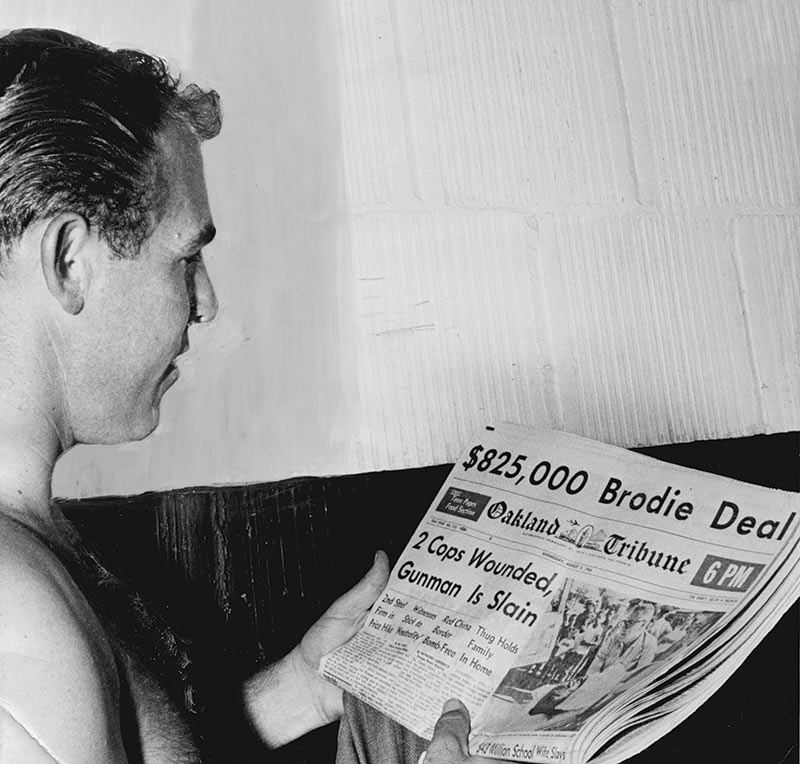

Everybody was losing it all when the established NFL and the rebel AFL, American Football League, were in a battle for the game’s stars. Rookies were being signed in secret, and then drafted.

Veterans, especially NFL quarterbacks whose contracts had expired—Brodie being Exhibit A—were offered enormous sums to change leagues. Brodie agreed to a deal with the AFL’s Houston Oilers (now the Tennessee Titans) and after a round of golf in August 1966 at Sharon Heights Country Club near Stanford, where he was a member, the foursome was eating lunch. A club member came to the table and said he just heard the leagues had merged. “Someone,” Brodie supposedly insisted, “owes me $750,000.”

So Brodie did not depart the Niners until his retirement after the 1973 season. His career was bittersweet. Because the Niners were not strong defensively, and with San Francisco so often trailing late in the game, he would be forced into throwing high-risk passes, and so he threw a lot of interceptions in critical situations. Despite at times leading the NFL in passing he was booed repeatedly by the home fans. You wondered why he didn’t chuck the helmet and shoulder pads sooner to pick up a driver and putter.

He didn’t get to the Super Bowl, which wasn’t created until the 1966 season after the merger. He didn’t even win a conference championship—or rather the 49ers didn’t. Brodie used to say that in team sports, unlike golf or tennis, it’s wrong to blame an individual for the outcome, wrong to call a player a loser or winner, because it’s a group effort.

When, in the late 1950s, Brodie attempted to play both football and pro golf (all sports were different then, with fewer games and less organization) he found it to be overwhelming.

“I learned as a pro you could handle only one sport at a time if you wanted to be successful,” Brodie said. Maybe this was also because for a while he traveled with Lema, another Oakland kid, who was just out of the Marines and a confirmed fun-lover, just a bit too much of one for Brodie, who could lift a glass or two himself. In 1962 Lema promised the writers covering the Orange County (California) Open that if he won he would buy them Champagne. He won, stayed true to his word and was nicknamed “Champagne Tony” thereafter.

Brodie’s education as a golfer, winning a match in the 1981 British Amateur at St Andrews and playing in the 1959 and 1981 U.S. Opens—as well as playing in those big dollar games in the San Francisco area—was hardly lacking. And when he joined the Champions Tour in the late 1980s, he understood what he knew and what he had to learn.

“I never quit playing golf since I started when I was at Stanford,” Brodie told the Los Angeles Times in November 1985. “I played amateur golf for 27 years. I know there is a difference between amateur and the pros. I know some people say I don’t have pro experience, but there is always room at the top and grumbling at the bottom. It’s the same in every sport.”

You could say the same about life. Yet even after the stroke that has kept him in a chair and off the course, despite not playing for a different team or having the ball fall a bit differently in golf, there is no grumbling from John Brodie—if not a legend, exactly, certainly one of the greats.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |