ate last year, Ben Crenshaw received a letter from the Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, inviting him to become an honorary member. The letter came from the golf club that ignited Crenshaw’s lifelong fascination with golf history and architecture, and the club that staged one of the most memorable Ryder Cups of all time, when Crenshaw was captain of the U.S. team.

“They just made me an honorary member, and I am just about as pleased as I can be about that,” says Crenshaw, the 73-year-old Texan. “Somehow, I have always felt a connection to that place, and it means so much to me. That club led me to have so much appreciation for history, for architecture, and for the privilege of playing golf at one of the very first American golf clubs.”

The Country Club was founded in Brookline in 1882, and its first six holes opened for play in 1893. It is one of the five founding-member clubs of the United States Golf Association, which was established in 1894. The Country Club hosted the 1913 U.S. Open, which delivered golf from gentlemanly obscurity into mass appeal in America, thanks to the unlikely champion, local caddie Francis Ouimet.

Amateur golfer Ouimet was 20 at the time and had grown up in a modest home overlooking the 17th hole of the Country Club. He was a clerk in a local sporting goods store and had to ask his boss for permission to play in the U.S. Open. Ultimately, this unassuming local—with his bag carried by a 10-year-old caddie—defeated legendary English professionals Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in an 18-hole playoff. The Boston crowd celebrated wildly, hoisting Ouimet onto their shoulders. American golf had its first people’s champ.

“Bernard Darwin was the London Times correspondent that week of the 1913 U.S. Open,” Crenshaw says, “and reading his coverage inspired me to read everything he ever wrote. I have got all of his books, and his work meant a lot to our game as a whole.”

Crenshaw had not traveled much beyond Texas state lines before he first set foot on the pristine turf of the Country Club as a 16-year-old in the summer of 1968, having qualified for the U.S. Junior Amateur Championship. Crenshaw—who had won the Texas junior title in 1967—played well and reached the quarterfinals, and he departed with a fresh perspective on the game. He wrote in his autobiography, A Feel for the Game, “In one wondrous week . . . I grew up a lot. The Country Club was, for me, the fountainhead.”

More than 30 years later, Crenshaw—by then a two-time Masters champion (1984 and 1995) and a four-time Ryder Cup player—returned to Brookline as the U.S. captain for the 1999 Ryder Cup. Crenshaw’s home team was heavily favored to win, but an inspired European performance over the first two days saw the visitors build a 10–6 lead. With just 12 singles matches left to play, the U.S. team faced a deficit that no other Ryder Cup team had overcome, but Crenshaw was defiant.

“I’m going to leave you all with one thought,” a beleaguered Crenshaw said as he closed his press conference on the eve of those singles matches. “I am a big believer in fate [long pause], and I have a good feeling about this, and that’s all I’m going to tell you.” They are probably the most famous words ever uttered by a Ryder Cup skipper.

Outsiders mocked, but Crenshaw’s team rallied behind him, wholeheartedly shared his faith, and duly delivered a comeback never seen before in the Ryder Cup. The home team won the first six singles matches, and ultimately took 8½ points from 12. When Justin Leonard holed an incredible 45-foot putt on the 17th green in the ninth match against José María Olazábal—with Crenshaw kneeling nearby, beside himself with nervous tension—victory was almost assured. One hole later, the final score was USA 14½–Europe 13½.

The Country Club’s 17th green was critical in the singles, just as it had been in 1913, when Ouimet holed a birdie putt there to force the U.S. Open playoff. In the playoff, he birdied 17 again to open up a three-shot lead with one hole to play. No wonder Crenshaw believes in fate.

“For some reason, I thought that place was going to take care of us somehow, that week of the Ryder Cup,” shares Crenshaw, now recognized as one of the finest course architects of the current generation, along with his design partner, Bill Coore. “It was a notion, it was a hopeful notion, but darned if it didn’t manifest itself. There was sentiment, no question, but somehow, on that Sunday, it was our time—and it was amazing to watch it unfurl.”

As it has unfurled over the years, Crenshaw’s career has been equally amazing to watch—with more than one turning point at Brookline’s Country Club. “Literally, once I left the club at the age of 16, I really wanted to understand and immerse myself in golf history and architecture,” Crenshaw recalls. “That place really just switched me on to it.”

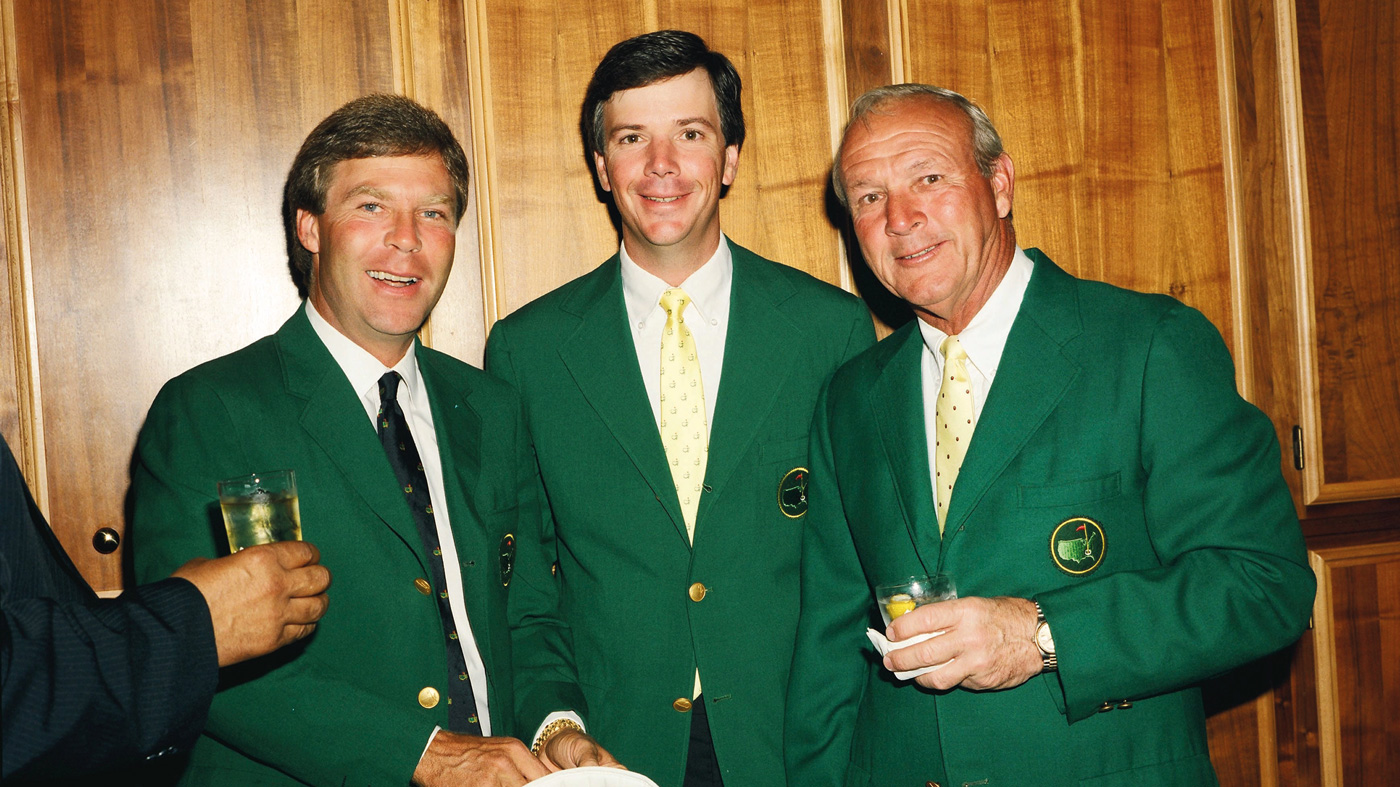

Crenshaw was 10 years old when he first saw Arnold Palmer up close, in 1962. “My father took me to San Antonio, to the Texas Open,” he says of a tournament he would win himself just 11 years later. “Arnold had already won two in a row, and he won this one, and it was as if the whole tournament was caught up in his wake. All eyes were on Arnold Palmer. He had so much charisma. There would be a crowd in the parking lot watching him change his shoes or re-grip a club. Having watched him for all those years as I grew up, it was such an honor to win his tournament at Bay Hill [in 1993]. Arnold was very kind to me, and I just loved being with him. He was like everyone’s grandfather. He had time for everyone, and he gave so much to professional golf and to all of us. There will never be anyone else like Arnold.”

Crenshaw has served as the player host of the annual Masters Champions Dinner since 2005. The tradition began in 1952, when fellow Texan Ben Hogan invited all past Masters champions to a Tuesday night gathering. In April, Crenshaw paid tribute to another Texan Masters champ, Scottie Scheffler. Said Crenshaw in front of the assembled green jackets, “Scottie, I love you, and I want you to keep doing well . . . and I know that you will play well this week. But there is one stipulation that we are going to ask of you: You are going to have to wear Ben Hogan’s right shoe, with an extra spike in it, so your right foot won’t move.” Crenshaw’s friendly dig, referring to Scheffler’s unique shot routine in which his right foot shuffles in the moment before impact, got the intended response. “Scottie laughed, and the others laughed,” recalls Crenshaw. “But you know, it is amazing to me to watch his right foot because the movement is different every time!”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |