ere, the lauded climber gets to ground level with Robin Barwick

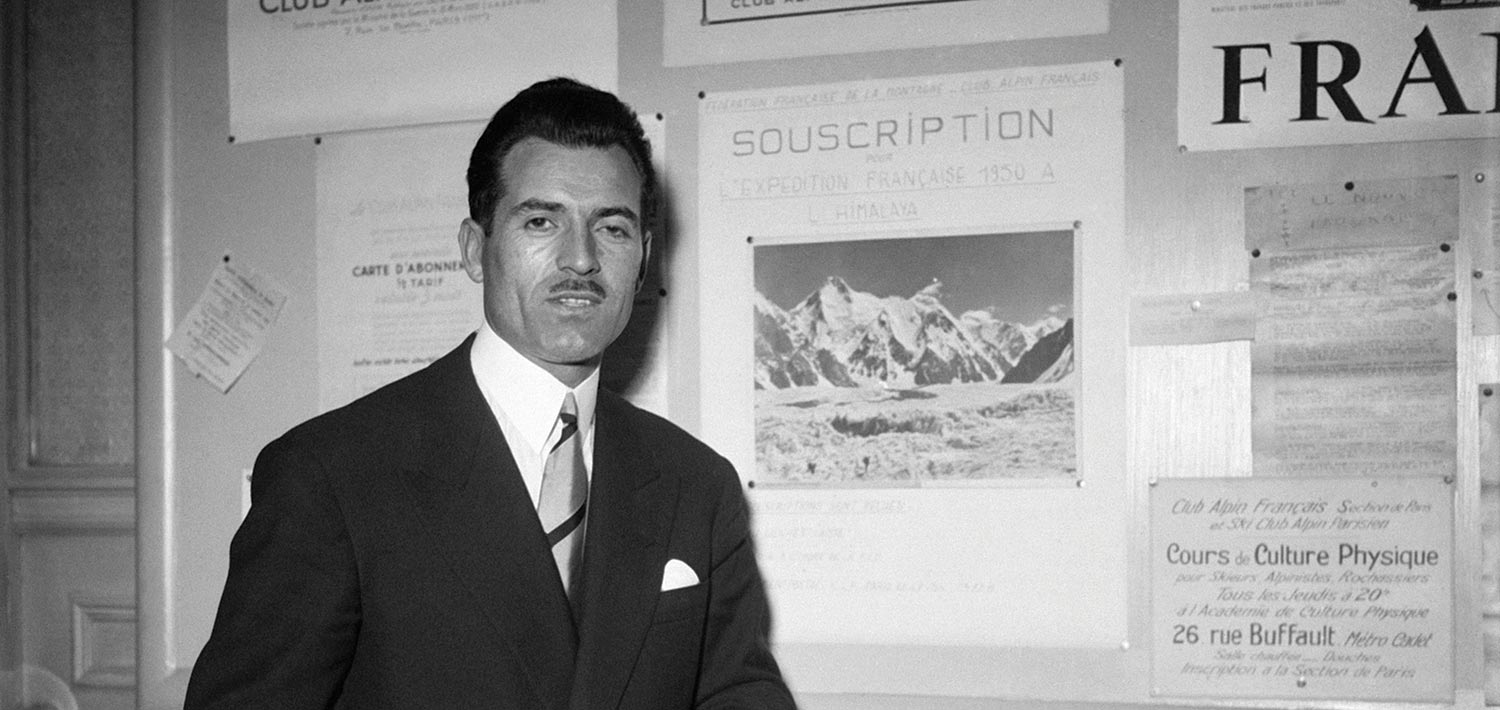

In 1950, Frenchman Maurice Herzog led a team up the mighty Himalayan mountain of Annapurna. One of only 14 peaks on Earth to rise above 8,000 meters (its summit reaches 8,091 meters above sea level), Annapurna is the 10th highest mountain in the world—but it is among the most dangerous and difficult to climb. It is named after the Hindu goddess of food and nourishment, who is said to live on the Nepalese mountain, yet the beguiling name belies a ruthless, forbidding, and unforgiving nature.

Herzog and his team defied staggering odds to reach the summit of Annapurna on their first attempt in 1950—a remarkable feat. Beyond just the climb, however, they were the first men in history to reach any mountain summit of over 8,000 meters. Accurate maps of the Himalayas were yet to be produced and so they could not even plan their ascent in any detail. Until they stood upon the peak of Annapurna in June 1950, it was widely considered impossible for man to reach such heights, literally, let alone make it back down to tell the tale.

Herzog did make it back down, but at a heavy price. At one point on the descent, he removed his mittens so he could get into his backpack, except that his mittens slid away from him and down a precipice. Gone. This moment’s lapse rendered severe frostbite in Herzog’s fingers inevitable and he would later have all 10 fingers amputated. Due to inadequate insulation provided by his leather boots, he lost all his toes as well. Herzog may have escaped the frozen clutches of Annapurna, but still, she brought his mountaineering career to a sudden end.

Herzog wrote a book, simply entitled Annapurna, which he dictated during his months of painful convalescing. It became totemic of a golden age of exploration and mountaineering in the 1950s and ’60s. Three years later, New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay became the first men to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain, Everest. It was another monumental achievement for mankind and it proved to an entire generation that they could realise their ambitions with some imagination, teamwork, and an iron will.

As Hillary later declared: “With practice and focus, you can extend yourself far more than you ever believed possible.” That message, and Herzog’s inspiring climb, reached Ed Viesturs, a teenager growing up in the flatlands of Illinois in the 1970s. Reading Annapurna, he said, inspired him to become a mountaineer.

“It’s the achievement on Annapurna that inspires, not the aftermath,” Viesturs would later write in his own captivating book, No Shortcuts to the Top. “Everybody helped everybody else down, carrying each other almost like victims from a battlefield. It’s a story of a band of brothers, of bonding and friendship and camaraderie… the complex mixture of hardship and perseverance that Annapurna elicited from those gutsy French climbers fired my imagination.”

From teaching himself to climb, to becoming a guide on the 4,392-meter Mount Rainier in Washington State, Viesturs would eventually realize his teenage ambition of becoming a Himalayan mountaineer. More than that, at the end of an arduous and treacherous 18-year campaign called “Endeavor 8,000”, he would become the first American to reach the summit of all 14 of the world’s “eight-thousanders.” The achievement is made more awe-inspiring by the fact Viesturs reached all 14 peaks without the use of supplemental oxygen. This matched the legendary achievement of Italian climber Reinhold Messner, who in 1986 became the very first person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders, doing so without oxygen.

Viesturs is the model mountaineer and a long-standing Testimonee for Rolex, the Swiss watchmaker that has been synonymous with mountaineering and exploration for nearly 100 years. Viesturs is a naturally gifted endurance athlete, with the mental fortitude to train hard and to push himself to his physical limits, yet what separates him from many other talented mountaineers is his clear thinking and decision-making at high altitude.

On the mountain base camps they talk about summit fever, when climbers get close to reaching a peak—tantalizingly close to completing what is probably a lifetime’s ambition—and despite time running out for a safe descent, or weather conditions worsening, or despite injury or illness, they continue upwards to the peak when reason dictates they should abort the attempt. Many mountaineers have lost their lives—experienced, talented, intelligent, courageous climbers—when they have continued upwards instead of turning around. Viesturs has lost many friends, but it is his insistence on sticking to clear rules that means he is still alive today.

Of Viesturs’ quotes, this is perhaps his most telling: “Getting to the top is optional. Getting down is mandatory.” It would make a good mountaineers’ tattoo, but it also illustrates a stark reality of his sport.

“I define risk in two different ways,” explains Viesturs, 62, speaking with us. “There are the objective dangers like avalanches, storms and rock falls, the things that can happen around you, and they can cause injury and death, and those are risks you just need to accept. But in my opinion, the majority of risk, from reading and watching and listening, comes from the decision-making, the subjective part. There are so many people who are willing to push for a summit no matter what the cost, whether it’s frostbite, needing to be rescued, running out of oxygen; they are not willing to turn around when they should, and that is what causes most of the problems on mountains.”

“On a climb, if you sense fear and trepidation internally, something is going on. You can’t always define what it is, but you have to listen to it. For me, having a more conservative attitude is something that kept me alive. It might have taken me longer to succeed eventually but so what? I am happy to be sitting here today.”

It was Viesturs’ ability to fend off summit fever that meant he required three attempts to reach the summit of Annapurna. The first attempt in 2000 failed due to mild weather and the resulting treacherous melting conditions on the north face, punctuated by avalanches. In 2002, Viesturs and his group attempted the east ridge, but he turned around when faced with more precarious conditions.

For the next three years Annapurna haunted Viesturs. It had become his nemesis.

When setting out to climb the eight-thousanders, it was not Viesturs’ intention to leave the ascent of Annapurna until last, but ultimately that is how it unfolded, with Viesturs finally, patiently reaching its summit on May 12, 2005, with his close friend and trusted mountaineering partner Veikka Gustafsson. Annapurna would keep him awake at night no more.

“Annapurna was a really hard nut to crack,” admits Viesturs with a hint of understatement. “I had kept asking myself if I could I ever do it safely. I was almost convinced, on that third trip, that if the conditions were just as bad as I knew they probably would be, I might have walked away and never gone back. Then I would still be thinking about it today. Thankfully we got there, the conditions were phenomenal, and I remember sitting on the summit, just elated that somehow we had pulled it off, but even then I had to contain that elation because we knew we still needed to go down.

“It was when I finally stepped off the mountain and took my boots off—that’s when I kind of let everything go, when I could think, ‘Wow, look at what happened over these 18 years.’ Somehow I survived it, somehow I stayed motivated. It was my greatest achievement. On Annapurna, everything came full circle.”

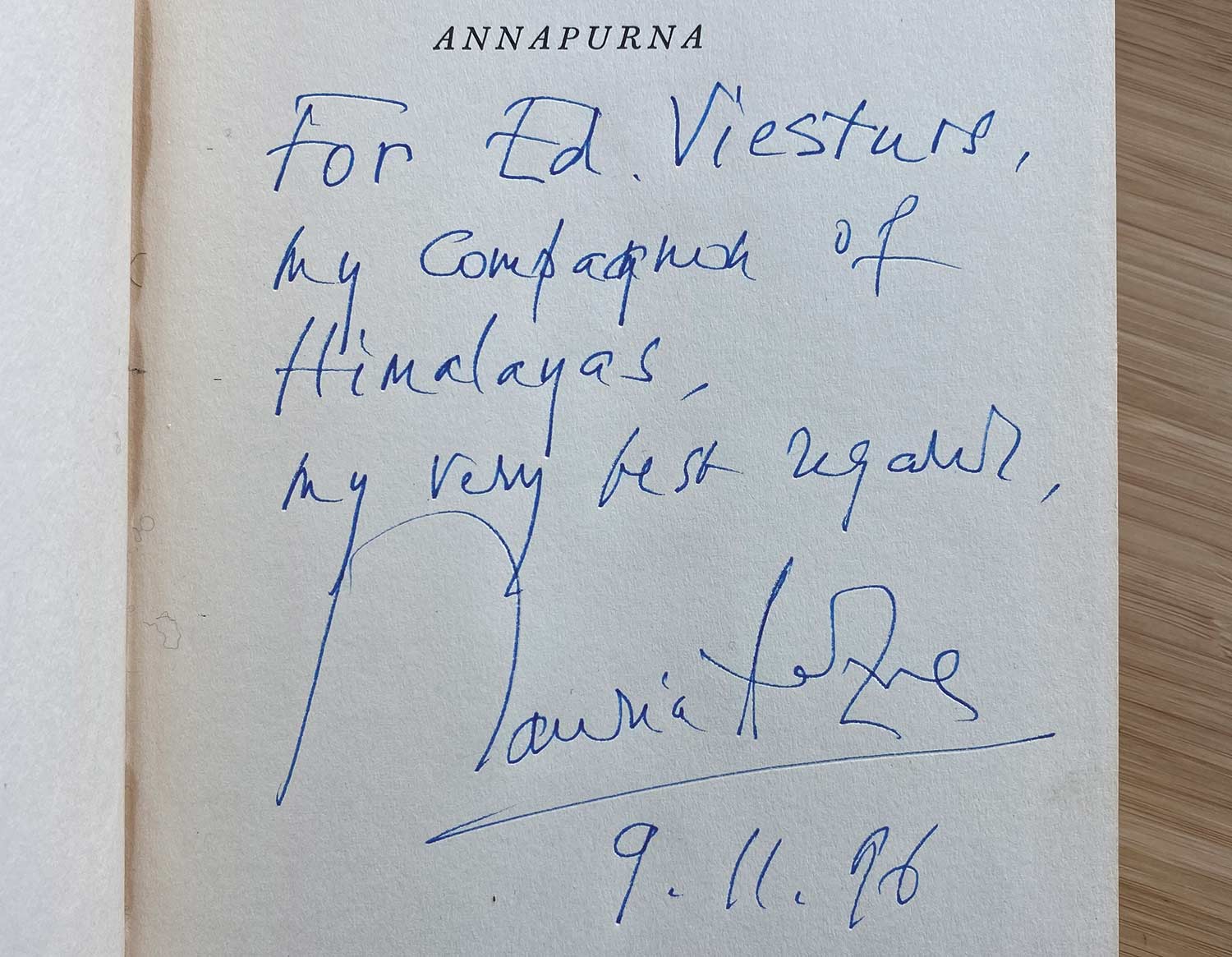

Herzog, the first to climb Annapurna, and whose book sold 11 million copies, died in 2012 at the age of 93. Back in 1996 he was at an event in Seattle with Sir Edmund Hillary. Sitting next to him was a 37-year-old Viesturs, then in the midst of Endeavor 8,000.

“I felt like a nobody sitting between two kings,” remembers Viesturs, who took along his copy of Annapurna in hopes that Herzog would sign it. Holding the pen between his palms, Herzog did just that—the acknowledgement from one pioneer of the Himalaya to another.

Ed Viesturs, a long-standing Rolex Testimonee, has had a career at the top: “When I was up-and-coming, a friend asked: ‘If you could have one more sponsor who would it be?’ Rolex came to mind because of its long association with exploration, with excellence, and the legacy of people associated with Rolex. It is an iconic brand of quality and endurance and the things I try to convey in the climbing world. Rolex sponsorship is a stamp of approval.”

After the momentous, first successful campaign to reach the summit of Everest in 1953, Rolex launched the original version of its Explorer watch. It remains an emblem of the close ties between Rolex and exploration, since the Swiss watchmaker had equipped Himalayan expeditions with its legendary Oyster watches since the 1930s. The Himalaya mountains even served as a real-life laboratory for Rolex development. The innovative Explorer II timepiece was introduced in 1971, complete with a 24-hour hand. It quickly became an essential tool for those exploring Earth’s most extreme conditions.

This year Rolex has extended its legacy in exploration with the launch of new generation Explorer and Explorer II timepieces, illustrating Rolex’s perpetual drive to improve.

Viesturs has worn a Rolex Explorer II ever since he received one as a gift. He says: “I still wear the same Explorer II that I got in 1994. It’s taken some bumps as it’s the watch I wore on all those climbs since then. It is part of me now. I have some other, newer watches that I wear occasionally, but I always gravitate back to my original Explorer II. My watch has that perfect patina, and there are memories there.”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |