Golf’s great tapestry would be void of much color were it not for the caddies. Many of the greatest players of all time would never have lifted a golf club had they not been attracted to the sport to earn their first dollars caddying. It has become a profession today that can be lucrative to a few, yet all the while the grassroots of caddying are being left in the shade

t is not a point of history to relay to your teenage children and grandchildren if they are aspiring golfers, but neither Ben Hogan nor Byron Nelson finished high school. Hogan left Central (Paschal) High in Fort Worth early and on the other side of town, Nelson ducked out of Poly High without a diploma.

But they still gained an education, on the golf course at Glen Gardens Country Club, where they had both caddied and played from the age of 13, in the late 1920s. Hogan and Nelson were contrasting personalities but they grew up together at Glen Garden where their games were honed in the furnace of their rivalry, firing each other on, and where they went at each other in the annual caddie tournaments.

Without wishing it to become a theme, Lee Trevino didn’t finish high school either. A difficult and deprived childhood saw Trevino picking cotton in Texas fields from the age of five, and he started caddying at Glen Lakes Country Club in Dallas (no relation to Glen Gardens) pretty much as soon as he could carry a bag without it dragging on the ground behind him, aged eight. The caddie master there was called “Cryin’ Jesse” and he took Trevino under his wing.

“Always tell the player that he’s swinging good, make an excuse for him, keep him positive,” says Trevino on caddying for club golfers. “Just get in the game with him, give him a little information.”

Jaime Diaz once wrote of Trevino on ESPN.com that, “No golfer has ever come farther on industriousness and grit”. Trevino won six major titles and it is anyone’s guess how many more he could have won had his back not been injured by a lightning strike in the 1975 Western Open.

Late in Trevino’s career he forged a close relationship with his caddie Herman Mitchell [Trevino & Mitchell pictured, above], who carried Trevino’s bag from 1977 until the mid-‘90s, when Mitchell’s health began to fail. Mitchell once admitted that he wasn’t sure how much money he made from carrying Trevino’s bag. Trevino paid the money into Mitchell’s bank account and Mitchell knew it was there.

“That’s the kind of friend he is,” said Mitchell. “I think me and Lee are as close as any caddie and player have been in the history of golf. He’s better to me than I am to myself. I love him like a brother.”

Not one to forget his own roots, Trevino continued to support Mitchell until his death in 2004.

Arnold Palmer was eight years older than Trevino and when Palmer was 12, in 1941, the United States entered the Second World War.

“The supply of local labor was so diminished that there [was] no shortage of jobs around the golf course my father wanted me to do,” wrote Palmer in his great autobiography, A Golfer’s Life, in recalling his childhood at Latrobe country Club in western Pennsylvania, where his father Deacon was the boss. “In the summers I worked at the golf course full-time, days that started before dawn and ended after dark, cutting fairways with the gang mowers and greens with a push mower in the morning, then working in the pro shop in the afternoons. I also served as the club’s caddie master and often caddied for the members myself.”

Palmer would earn a quarter for 18 holes (and one lady member would pay him a nickel for hitting her ball over a particular ditch) and it meant he could play against the other caddies on Mondays when the course was closed to members. It got his game sharp in a hurry and even though he won the annual caddie championship five years in a row from the age of 11, Palmer’s father Deacon never let the young buck take the trophy home. Palmer stewed over that for years.

Deacon once admitted that his son was the worst hire he ever made, because if the pro shop and golf course was quiet Palmer would run down to the first tee to hit balls. There was a slot machine in the pro shop too, and Palmer would “borrow” dimes from the pro shop till when no-one was looking to play the machine.

“Once, to my complete astonishment and sudden horror, I hit the jackpot and $20 of dimes flooded out,” admitted Palmer. “I waited nearly 40 years to tell my father this story, and he was not too pleased to hear it even then.”

In Germany a generation later, Bernhard Langer was eight years old, like Trevino, when he started caddying at Augsburg Golf Club, a five-mile cycle ride from home. In Germany in the late sixties and early seventies golf was far out on the sporting fringe. Langer was drawn by the opportunity to make pocket money as a caddie and his older brother Erwin showed him the ropes. The future Masters champ and Ryder Cup star would caddie and practice every day after school, all weekend, and in the summer vacations he would sometimes camp near the golf course to save the daily cycle commute.

Notorious for his attention to detail as an adult, Langer showed the same commitment to caddying and gained the nickname “Adlerauge”, meaning “Eagle Eye”.

The Augsburg caddies were allowed on the practice ground when it was empty and they shared a 2-wood, 3-iron, 7-iron and a bent putter given to them by a member. You learn how to strike a golf ball when splashing out of a bunker with a seven-iron, clubface opened wide.

It took four years of caddying before Langer, a bricklayer’s son, could afford his own clubs. The only instruction he had received by the age of 14 was from a sequence of eight pictures of Jack Nicklaus’ swing, stuck up on the wall of the caddie shack, but it didn’t stop Langer from finishing second in the caddies tournament with a 73.

As an aside, soon after that Langer sat in front of a local careers advisor and told him he wanted to become a golf professional. There were hardly any German professionals at all at this time—the one at Augsburg was a Trinidadian import—let alone any German role models on tour. The advisor said to Langer: “I have never heard of that [profession],” and walked out to see if the department had any information on being a golf pro. A few minutes later the advisor returned and said to Langer, “There is no such thing. Find something else to do.”

Thankfully, Langer’s stubborn streak was well developed at a young age.

Many of the game’s greatest players emerged from the caddy shack and there is an organic quality about kids earning their first quarters and Deutsche Marks on the golf course—or Euros and crumpled Abe Lincolns in today’s money. Carrying an adult’s golf bag is hard work for a kid, when they have to keep up while also raking bunkers, tracking down wayward tee shots and keeping the clubs clean. Young caddies learn manners in no time when a tip is on the line and they pick-up course management too. All that sweat stokes the desire to be the one striking the golf balls, rather than just finding and polishing them, and to one day show the old fogeys how it’s done.

Those shadowy old caddie shacks, stocked with dog-eared golf magazines and some other types of magazines, are occupied by electric cart generators these days.

“Golf clubs selling cart hire on top of every green fee has killed caddie programs,” was the blunt assessment of Tiger Woods in an interview with Kingdom magazine in 2014. “Young kids who want to make some money over the summer can no longer go and caddie and get introduced to the game of golf like they used to. When I was growing up I caddied in every mini tour event that I could; we’d ‘show up, keep up and shut up!’ The golf cart has changed that part of golf culture.”

Added Palmer in one of his regular Kingdom interviews: “Caddies have always been a very important part of the game. I learned so much from growing up being a caddie here at Latrobe. You learn how the game is played and how to behave on a golf course.”

In terms of managing a golf course, caddies were an inefficient factor where the hassle out-weighed the profit. Golf carts, on the other hand, are never late, they never fall out of line, they are genuinely low maintenance, they don’t expect tips and they bring in upwards from $25 a round. Easy money. Out the gate went personality, tradition and community spirit, and in came profit and efficiency. Deacon Palmer never liked the idea of cart tracks on his beloved golf course but he couldn’t halt the rise of their popularity.

Ever since golfers have trodden the links, so have caddies. The gentleman golfers of the mid-19th century in Scotland didn’t have golf bags and were happy to part with a couple of coins to pay a local boy for carrying his clubs, and so the caddying craft evolved from there.

The business of re-selling lost-and-found golf balls dates right back to these times too, and the young caddies of St Andrews would trawl the Swilcan Burn to recover the relatively expensive and handmade feathery balls, and then the more durable gutta percha golf balls that succeeded them. Entrepreneurial caddies were known for muddying streams as they “searched” for balls to ensure they could trick golfers into thinking it was gone for good. When Old Tom Morris served as Links Superintendent in the late 19th century he would occasionally need to admonish the mischievous caddies for trying to build damns along the Swilcan Burn, so as to deepen the water and increase the rate of lost balls they could retrieve.

It’s a far cry from caddying on the St Andrews Links more than a century later. Angus Hay, from Cupar, near St Andrews, is a caddie on the European Tour today, yet begun as a trainee at the Home of Golf at the age of 17 and he didn’t have to concern himself with re-selling lost balls.

“The first incentive to caddying was the money,” admits Hay, who currently carries for Sweden’s Joakim Lagergren. “It is quite motivating when you can earn upwards of £150 a day, cash in hand [or $190 at current exchange rate]. As a 17-year-old that was a lot of money. You would work two rounds a day and take a fee of £40 per round but if you did a good job you would often get tipped well. It was luck of the draw each day.”

In the Scottish off-season, Hay spent a couple of winters caddying at Old Collier Golf Club in Naples, Florida, and at other local high-end clubs that persevered with caddie programs, and hooked up with former PGA Tour golfer Mark Lye, who needed a part-time caddie for senior tour and local tournament appearances.

Hay was fast-tracked through the ranks at St Andrews and Lye picked him from a squad of caddies at Old Collier where Lye was membership director, so there must be something about him that works.

“People say about me that I am always in the same mood,” admits Hay, “whether we are five over par and missing the cut or 15 under par and in with a chance of winning. I try to stay level-headed and not to get ahead of ourselves. The caddie has to be the same as a golfer in that regard, taking one shot at a time. If you start thinking ahead too much a tournament can get away from you.

“Certainly compared to 15 years ago, caddies are becoming a lot more professional. There is a lot less drinking on tour than there was and you don’t get caddies turning up to the golf course hungover anymore. I can even see the difference between now and when I started seven or eight years ago. I mean, we know how to celebrate when the time is right, don’t get me wrong, but if you are going to caddie on tour today you have got to be on time every day.”

There is considerable evolution separating Hay and his fellow countryman “Mad Mac”, who caddied for England’s Max Faulkner when he won The [British] Open in 1951. Mad Mac would always wear a long raincoat with no shirt, and a pair of binoculars hung from his neck, without lenses, with which he would read putts. He would say to Faulkner: “The putt is slightly straight, sir”.

Hay found his own pathway to tour caddying, whereas his friend Oli Briggs found a more circuitous route. Briggs, an Englishman, was caddying at a club in Melbourne, Australia, when Kevin Rhoderick, a former relief pitcher with the Chicago Cubs, asked him to become his caddie as Rhoderick tried his hand on mini tours. They worked together for a few months, based in Scottsdale, but when Rhoderick’s golf lost steam he left Briggs with the appetite to work on the main tours. Briggs found work with Australian journeyman Terry Pilkadaris on the Asian Tour, before finding his way back home to the European Tour, where Briggs now plies his trade.

“Terry helped me more than anyone,” starts Briggs. “He has been on tour for years and he’s won countless times. We never missed a cut together and he helped get my confidence up and when I came back to Europe it helped me get a job because I had worked for Terry.”

Briggs has won on the European Tour, carrying for Sweden’s Alex Bjork, and he is now working for Nicolai Hojgaard of Denmark.

“To be a caddie you need a good spine on you,” says Briggs. “These pros are relentless. This is their livelihoods and their ‘everything’. You need to be very sure on the golf course because the pros will question everything you say. If you doubt yourself as a caddie then the pro sees that and that is when they start to worry.

“If a caddie fluffs his lines you can see the golfer’s body language drop immediately. If the golfer loses confidence in their caddie they can begin to lose confidence in their own decisions.”

The best club caddies can find their way onto the tours these days, where there is a lot of money to be made by a fortunate few. It is often reported that at the height of Tiger Woods’ playing career, his (former) caddie Steve Williams was the top-earning sportsman in New Zealand, his homeland, as he would earn up to 10 percent of Woods’ prize money.

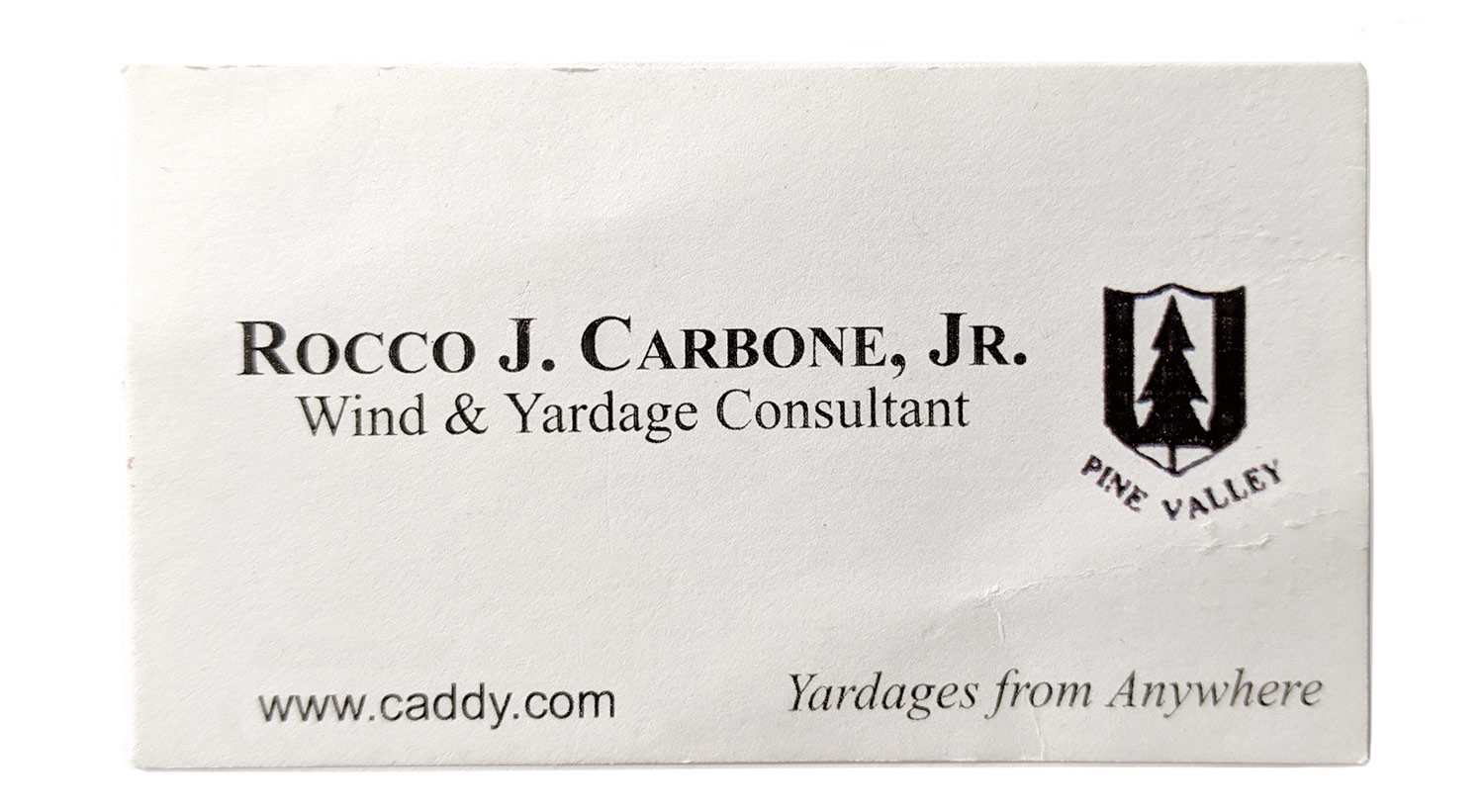

There are less opportunities for caddies to make a living working at clubs in the 21st century and the sport is poorer for it, even if the clubs are making more from carts. Rocco J. Carbone is in his early 70s now and retired, but he was a renowned caddie at Pine Valley GC, New Jersey, for 36 years. He even had a business card that read: “Wind and Yardage Consultant”.

Rocco is old school and didn’t always worry about propping up his golfer’s confidence. According to Rocco when we called him recently: “If a golfer says, ‘I want to take a 5-wood but it might be too much’, tell him to hit it fat.”

Rocco carried the bags of some of America’s highest rollers at Pine Valley, including Michael Jordan.

“Michael Jordan, really nice guy,” shares Rocco. “Let me tell you something; he said he was going to play on the seniors tour but I had more chance of dunking a basketball and I’m 5-5.”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |