Top down, pedal down. America might not have invented roads, but it’s fair to say she invented road trips. Here, the editor checks the mirror to see how we got rolling

Evolved out of the dust tracks and wooden crosses left along countless miles by settlers, immigrants and refugees, the American road trip was a consequence before it was a purpose, before it had a name. Today it’s on the radio, in the windows down, in the rise and fall of a hand surfing over the warm rush of tires on asphalt. Not gifted like before, no longer inevitable, the road trip today must be sought out, fought for through the haze in modern vehicles, quiet cool air spilling into clean cabins, pretty lines on screens, ETAs, advance bookings, alerts and the falsely reassuring voices of hands-free loved ones too far away to do much good. No more hissing hot spit junk metal, ruined shirt wrenching the cap off the radiator, sprung parts or sad little pops before a roll to the shoulder. Not often, anyway. The best stretches were slow easy miles, new smells and familiar rattles, long hours with friends or alone, skipping past the preachers in search of a song. Even now it’s never through the windshield, always to the sides in wax paper-wrapped chiles, racks of keychains and gas station toys, beautiful oddities and wide vistas, glimpses of possible loves, possible lives, then leaving it all behind to drive on. The road trip is as American as the wanderlust from which it grew, and as charged with possibility as America herself. And whether the engine is running or long dead, the truth is that road trips never end, they only begin.

“What I can tell you is that every trip, in the beginning, was a road trip,” says Leslie Kendall, Chief Historian at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles. “Anything could happen. You were never guaranteed to get where you were going, and so road trips are about the journey, not the destination. Ideally they allow you to experience America at your own pace, at ground level, with the top down and with people you love.”

The first known roads were found near Jericho and date to 6000 BCE, just animal paths that humans followed. People started building roads themselves 2,000 years later, as evidenced by ancient stone-paved streets in Iraq and timber roads in England. Then came the Romans in 312 BCE with their Via Appia, Appian Way, from the Middle English word for road, wey, itself from the Sanskirt vah, which means “carry,” “go,” or “move,” according to Britannica. The Appian Way was the first 162 miles of a nearly 53,000-mile network of well-engineered highways that connected the world to Rome. Highways as the roads often were elevated roughly three feet to help with drainage and to mitigate undulations in terrain.

There was the Silk Road (130 BCE to 1453), Japan’s Gokaidō “Five Highways” (1603 to 1868), a Siberian highway completed in the mid 19th century and more than 24,000 miles of Inca roads in South America, many of them paved with stones. Millions of travelers over nearly 8 millennia and yet the term “road trip” paints a distinctly American picture. The reason why has to do with Kendall’s “top down” image and a frontier culture that left trains and cowboys behind once Henry Ford’s assembly line started rolling and America started building roads.

The American road trip’s evolution has roots in the Good Roads Movement, a lobbying effort between the late 1800s and the 1920s to get the U.S. government into the business of road improvement—and in fact roads at the time were godawful, especially in-between cities. Of his 1909 car trip in Wyoming, one early motorist later reflected: “Roads? Yes. The state had plenty of roads, such as they were, but most of them for long and frequent stretches were worse than none. Deep ruts; high centers, rocks, loose and solid; steep grades; washouts or gullies; stumps; sage brush roots; unbridged streams; sand; alkali dust; gumbo; and plain mud were some of the more common abominations.”

And so it was across the country.

“It used to be that if you were going 20 miles you had to have a spare tire,” says Bob Toth, Director of Industry Relations for Goodyear, a company that began operations in 1898. “On a road trip you had to carry two tires minimum, and really as many spare tires as you could, otherwise you were going to be stranded.”

Tires weren’t the half of it. Vol. 1 of Motoring West: Automobile Pioneers 1900-1909 quotes various early guides as recommending drivers bring items such as (but not limited to) extra food and warm clothing; an evaporative water bag; an axe; shovel; 100 feet of rope; a three-foot iron pin and a block and tackle; extra electric light bulbs; spark plugs; tire patches; a fire extinguisher; a supply of annealed wire; a pair of side-cutting pliers; tent; duffle bags; a gasoline stove; aluminum kettles; a coffee pot; and (because you can never have enough) tape.

The Good Roads Movement sought to take some of the adventure out of motoring, or at least lessen the pain. Perhaps ironically it was founded mostly by bicyclists, who championed improved roads via demonstrations, conventions and pressure on political candidates. There was even a Good Roads Magazine with a circulation of 1 million, but the cyclists were pushed to the side once the car crowd arrived, the latter’s superior transit potential immediately obvious to anyone within earshot of a combustion engine—and earshot was as close as many Americans got at the time. Cars were wildly expensive, as was maintaining them, especially given the dearth of filling stations and garages outside of metro areas. But then along came Henry Ford and his moving assembly line, and everything changed.

When the Ford Model T debuted in 1908 it cost just over $23,000 (in 2019 money), roughly 18 months of an average salary. But by 1925 a new “tin Lizzy” (as they were called) could be had for $3,790, just three months’ average salary, because of improved production efficiencies and volume.

By 1918 half of the cars in the United States were Model Ts, with a total of 16.5 million sold before the model was phased out in 1927.

With the Model T the middle class finally had their cars; now they just needed Good Roads—and those, to use a terrible pun, were just around the corner.

Thanks to the efforts of the Good Roads crowd and to the obvious need for better roads, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, getting government into the roads business. By then, the Lincoln Highway and Dixie Highway had opened, in 1913 and 1915 respectively. Both backed by Carl G. Fisher, an early auto industry champion and founder of Indianapolis Motor Speedway (among other things), the former connected Times Square in New York City with Lincoln Park in San Francisco while the latter connected Miami to Canada. Though both were important, it was a different road that would capture the country’s—and even the world’s—imagination: U.S. Route 66.

Running from downtown Chicago to Santa Monica, California, Route 66 opened in 1926 and was instantly popular, joining many farms and small towns with metropolitan areas for the first time. Due to its timing it became the road of the Great Depression, the “Mother Road” of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath that delivered desperate families out of the Dust Bowl and to the West Coast. It offered hope and adventure in the same trip, and perhaps that is one of the reasons why it became so beloved. But if the migrants and refugees were focused on getting to their destinations, somewhere along the way the road became more than a means to an end—it became an experience and then, in some senses, it became a movement.

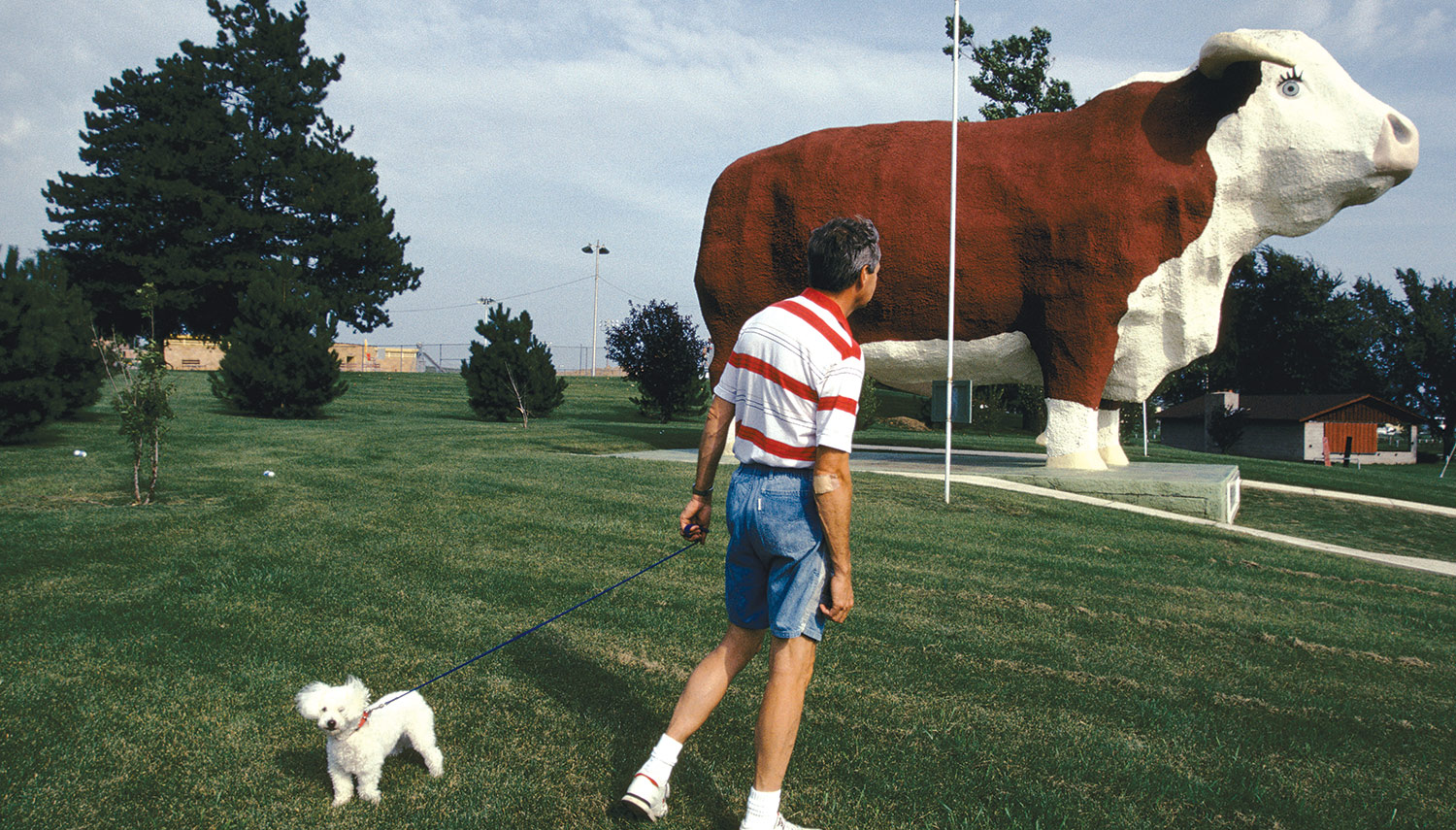

In delivering rural Americans to big cities and freeing urbanites into the wilds, Route 66 created an entirely new demographic of those who traveled its 2,448 miles. No matter their backgrounds or economic situations, Route 66 travelers all could discover their country anew, or for the first time. More importantly, they all were having shared experiences. The Meteor Crater and Petrified Forest in Arizona; Brush Creek Bridge in Kansas; the art deco U-Drop Inn Café in Texas and so many other points of interest, some natural and some quite unnatural. Neon signs, giant balls of yarn, hotels comprised of wigwams and an ever-changing landscape out the windows—there was so much to see. And so, for the first time, “the road” was a destination.

This notion really landed after WWII, when a generation of GIs came home in search of new adventures. They found them on the road, which now had a soundtrack as well. (Get Your Kicks on) Route 66 was released by Nat King Cole in 1946 and was an instant hit on the Billboard charts, charting again the same year in a version by Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters.

Songwriter Bobby Troup had written the piece during a 10-day road trip on the title highway and hardly could have imagined it would go on to be covered by such artists as Chuck Berry, the Rolling Stones, punk band The Cramps and electronic group Depeche Mode, among many others. And if the song or others like it didn’t compel one to hit the highway, Jack Kerouac’s seminal work, On the Road, probably did. Published in 1957, it documented cross-country road trips Kerouac had taken with friends in the early 1950s, and with pronouncements such as “the road is life,” On the Road was the journey motif redefined by America. No longer did heroes have to go after a specific objective to find honor, revelation or redemption. Kerouac and the Beat Generation said it was enough simply to go, that the epiphanies would come, and that direction wasn’t the point. It might have been the only option for a restless people who, after a century of moving west, finally had hit the Pacific Ocean.

Bob Dylan said On the Road “changed my life like it changed everyone else’s,” but there were other inspirations as well.

Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley in Search of America came in 1962. Songs like Roger Miller’s King of the Road (1965) and Simon & Garfunkel’s America (1967); and the movie Easy Rider in 1969. A popular Route 66 TV series ran from 1960-64, with two restless youths finding adventure on the road, and since then there’s been no shortage of road trips in media. But as for the road trip itself… Top down, wind in your hair, turn up the radio, put down the pedal, and the whole thing is so American, so rock ’n’ roll romantic, that you just knew it couldn’t last.

Right as the road trip was hitting its stride, its golden age ended. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had authorized the creation of America’s Interstate Highway System in 1956, a year before On the Road was published, and whether or not anyone saw it at the time it marked a downshift in the road trip’s inevitability. The new system was about being able to move military equipment with straight-line efficiency across the country. The journey was a necessary evil, and so roads like Route 66 were absorbed and all but disappeared, the small towns and farms through which they passed mostly left alone again, their boom businesses mostly shuttered. A few originals remain, like the Blue Swallow Motel in Tucumcari, New Mexico. It opened in 1939 and still welcomes travelers today to its charming rooms with attached garages. On the Lincoln Highway as well, there are monuments and old attractions, diners and such still there to be discovered, but fewer people today take the time.

“You think of a 1922 Studebaker or something like that,” Kendall says. “You are going to have an adventure, it will break down, you will have interesting problems. Hopefully you turned that ordeal into an adventure and learned a little something. It was about seeing the sights, seeing the desert—look at the saguaro cactus, look at the other desert plants. Then go through the heart of America and look at the wheat wave back and forth in the breeze, go a little farther north and you experience lakes, different terrain, different foliage, doing it at your own pace and with whom you want.

“Hopefully you don’t get killed along the way or wreck or something like that. It’s about the adventure, but today it’s less so.

People have road trips, but you’re essentially in your isolation chamber on wheels, windows rolled up. Convertibles aren’t practical anymore; people go too fast for it to be fun. It’s one thing to have the wind in your hair, another to be beaten to death by your hairdo. You think of cruise control or autonomous vehicles, what’s coming; you watch the world go by at 60, 70, 80 miles per hour and you just can’t wait to get where you’re going. It’s a little bland.”

Steven Hileman agrees. The VP of Marketing for the TOGO Group and the Roadtrippers app says his company is trying to resurrect the classic road trip—using the same technology others might blame for helping to kill it.

“Roadtrippers was founded based on this idea of ‘The Great American Road Trip’—Route 66, really,” says Hileman, with his company dedicated to creating “the leading technology platform for road-based travel and outdoor tourism.”

Plot your next road trip into Roadtrippers and it will highlight points of interest, some quite obscure, along the way.

“All of the amazing stories of Route 66, the small towns and interesting things to do along the route… We’ll show you where they are and how to get there. So many of today’s mapping and navigation solutions are optimized to get you somewhere as efficiently as possible—that’s the antithesis of a road trip from our perspective. Sometimes we say that Roadtrippers makes your trip longer. We’re helping you have an amazing trip, not an efficient trip.”

More than just helping travelers to find many of the classic road trip stops, the people at TOGO are considering if those stops can be transformed, perhaps into charging oases for electric vehicles, not only saving the stops from extinction but also elevating them past their original purpose as roadside curiosities.

“Think about the ability to one day create charging stations around points of interest like The World’s Largest Thimble or the Longerberger Basket Headquarters [a giant basket]. You need between 15 and 45 minutes to charge an electric vehicle, depending on your needs. Pop up electric charging stations in front of these sites, add dining and facilities, and suddenly the future of vehicle refueling is actually a series of micro-experiences scattered all over the U.S.”

Looking further down the road (sorry), Hileman wonders if the road trip could come to define how we live, not just how we travel, with RVs such as the iconic Airstream—“maybe the ultimate road trip vehicle”—effectively making the road trip a lifestyle.

“It’s a little bit chaotic but possible, right?” he says. “There’s actually a growing movement of nomadic folks today, and yes you’ve always had nomadic people, even going back to 1970s’ songs about ‘the guy living in a van down by the river,’ you always had that group, but it was particularly painful from a lifestyle perspective. There are more conveniences to that now, a lot more that technology enables. You can work from anywhere, so why not? I’ll always believe that there’s a certain section of the population that is willing to be explorers 100 percent of the time.”

For anyone who’s taken one, road trips linger, their miles are traveled over and over long after the engine is shut off, for a lifetime even. Perhaps they are the American mantra, the American meditation. Once a consequence, then a purpose, their future likely will be more about awareness than motion for, depending on one’s vehicle of choice, travel itself no longer guarantees adventure. But for those who keep the windows down, the road trip remains the best way to find the country, and perhaps yourself—at your own pace, with people you love or alone, top down, the wind in your hair.

“We exist for experiences, we don’t exist just to exist,” Kendall says. “And it’s not that everyone is hedonistic, but we want to have good experiences and we have a whole lifetime to accumulate them. That’s why people travel, and this is a way to do it. As long as you don’t die or get arrested and you end up with a good story, it was all worth it.”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |