Robin Barwick reflects on the amateur spirit of Bobby Jones and the Victorian heyday of amateurism

Robert Permedus Jones, born 1879, could have played major league baseball. With his big hands, sturdy build, sharp eye and smooth swing he shone playing first base for the Mercer University Bears in Macon, Georgia for three years, before transferring his star quality up-state to the Georgia Bulldogs in Athens for his senior year.

But his father, Robert Tyre Jones, a prominent businessman in Canton, 40 miles north of Atlanta, never watched a game. In his book, ‘The Masters—Golf, Money and Power in Augusta’, Curt Sampson writes that when a friend told R.T. Jones of his son’s potential he retorted: “You could not pay him a poorer compliment”.

Before they were called the Dodgers and decades before L.A. beckoned, the big-time National League outfit from Brooklyn was called the Superbas, and the story goes that R.P. Jones had signed on the dotted line for the Superbas before his domineering father threatened to disown him. R.P. conceded, passed his bar exams and established a successful law firm in Atlanta.

R.T. Jones was not mean but he was 19th century old school and life had not always been kind. As a young man he had to cope when his own father, a prosperous farmer in Covington, was murdered—shot on his way to buy a field with $300 in his pocket.

These were Victorian times, when sports were for fun on sunny afternoons, not for careers. This was when golf professionals were not allowed into the members’ bar and in these fledgling days of pro baseball the prospect of R.P. getting on the train to New York must have seemed to R.T. like running away with the circus.

The path R.T. knew to prosperity did not involve sports. He was a staunch Presbyterian who believed that success in business depended on glorifying the Lord as much as it did on making a profit. He wouldn’t even drink Coca-Cola, so R.P. must have enjoyed the sweet taste of irony years later when Coke became his firm’s client.

Robert Tyre Jones II—Bobby—was born in 1902, full to the brim with his father’s natural athleticism but also with his grandfather’s pragmatism. Bobby would become the greatest golfer of his generation, with his peerless playing career culminating in 1930 when he became the only golfer ever (to this day) to win the British Amateur, British Open, U.S. Open and U.S. Amateur in the same year. And with that staggering accomplishment he promptly retired at the age of 28.

This is how good Jones was: in the summer of 1927 he played a series of friendly matches against Tommy Armour, the “Silver Scot” and reigning U.S. Open champion—and ultimately a three-time major champ—yet Jones had to start giving the famously combatant Armour shots, one-a-side. Jones was so hard to beat that throughout his career, against amateurs and professionals, no golfer ever defeated him in match play twice.

Jones was so good that even his grandfather softened. A message from R.T. to a young Bobby read: “If you must play on Sunday, play well.”

Jones’ pragmatism came in the fact that he never turned professional and after an exceptional academic career, followed his father into a career in law.

Historian Stephen R. Lowe writes in Georgia Historical Quarterly: “[Bobby Jones’] commitment to family, education, duty to country, personal modesty and of course amateurism and sportsmanship are all indicative of the traditional values of his grandfather’s generation. On the other hand, his willingness to violate Prohibition, his heavy smoking, and his decision to organize so much of his life around a sport, even if as an amateur, are manifestations of the modern values of his father’s generation.”

Jones himself would write: “My wife and children come first, then my [legal] profession. Finally, and never in a life by itself, comes golf”.

“Jones never entertained thoughts of playing golf professionally,” wrote Charles Price in his book ‘A Golf Story’. “He had vast other ambitions… He held a degree in mechanical engineering from Georgia Tech, a degree in English from Harvard and had quit law school after his second year at Emory University because, just to see how difficult they would be, he had taken the bar examinations, passed them, and so went directly into practice.”

Jones has been described as the “complete amateur” and “unsullied” by professionalism. Ben Hogan, the greatest player of the era immediately following the Second World War and the Masters champion of 1951 and 1953, once said: “Jones was a winner but anyone can be a winner. It was the way he won that made him strand out above all others.”

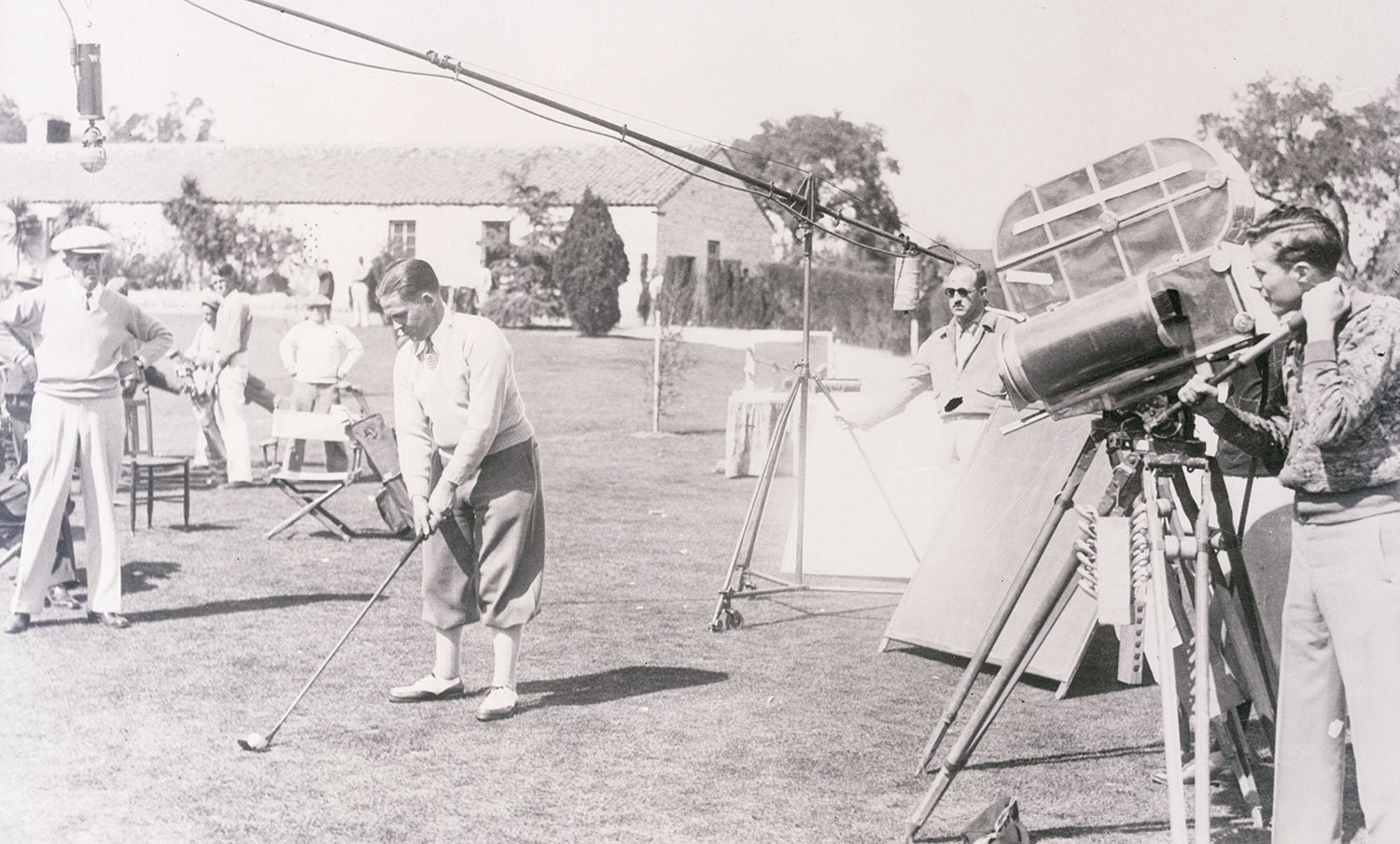

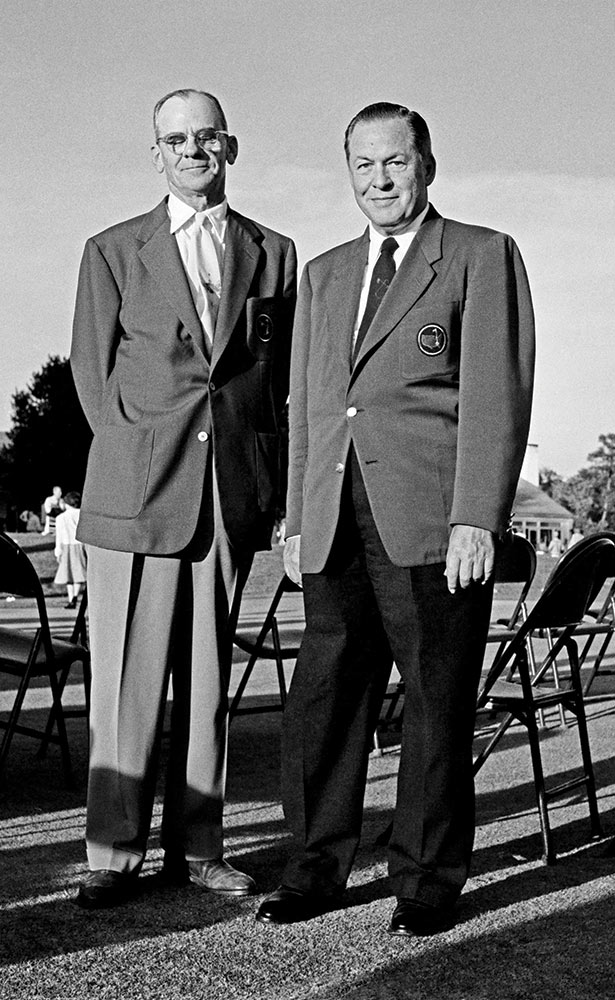

Jones’ sense of sportsmanship and courtesy was unerring, yet his resistance to professionalism on the golf course paid healthy dividends off it. Within a year of his retirement from competition in 1930 he had produced two series’ of instructional films for Warner Brothers in Hollywood that paid a fortune to the tune of $240,000. He also enjoyed a lucrative equipment deal with Spalding Brothers and among other interests, opened Augusta National Golf Club with friend and business associate Clifford Roberts, and established the Masters in 1934.

Walter Hagen, 10 years Jones’ senior, is said to have been the first pro golfer to earn $1 million, yet he never signed a contract to compare to Jones’ Warner deal.

Jones was devoted to the amateur game but the PGA Tour did not yet exist and the career prospects as a pro had few of today’s enticements. Tour pros in the 1920s and ‘30s had to strike a balance with the stability of club jobs. Jones is often described as a paragon of amateur virtue—and he was probably very close to matching the stipulations of the Creed of the Amateur, that was later written by USGA president Richard S. Tufts (see excerpt)—but this was glorification ascribed by an adoring media and public and anathema to Jones’ modesty. Jones had keen commercial acumen, and as he said in a 1927 interview: “Of course it’s nice to have people say nice things about you, but honestly, when New York papers make me out such a glowing example of moral discipline I don’t know what to make of it.”

Probably the last great career amateur golfer in America was Bill Campbell, who won the U.S. Amateur title in 1964 and went on to become president of the USGA.

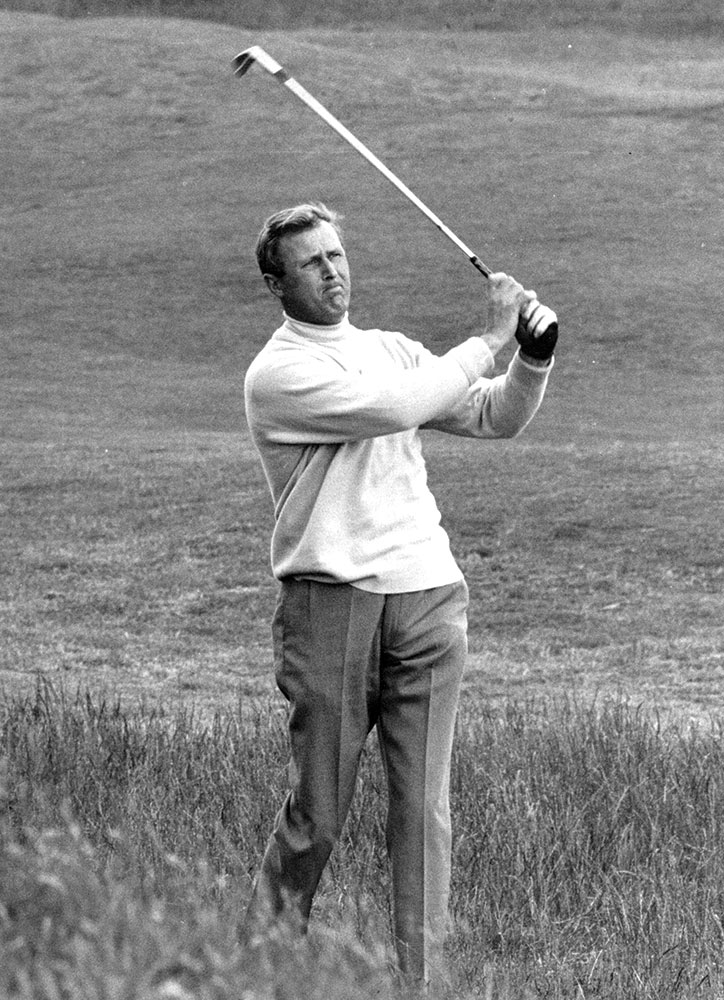

Former USGA executive director Frank Hannigan used to recall a conversation that illustrated the widely held respect for Campbell: “I was talking with Jack Nicklaus about the USGA’s amateur status rules, including a prohibition against accepting free balls or clubs from equipment manufacturers. Nicklaus, who had turned professional by this time, was telling me the rule should be changed. He asserted that the prohibition was unenforceable. ‘Name one top amateur who doesn’t take anything from the manufacturers,’ Nicklaus said. ‘Bill Campbell,’ I replied. Nicklaus paused for a moment. ‘Okay, you can have Campbell. Name another one.’”

Campbell died at the age of 90 in 2013, but gave what might have been his last interview to Kingdom magazine weeks before he died.

“You don’t find lifetime amateurs anymore,” said Campbell. “Why? Well, it’s easy to understand when you consider the increase in prize money and the corollary money that come with being a touring pro.”

The UK has its equivalent to Campbell in Sir Michael Bonallack, who was British Amateur champion five times and the only golfer to win the title three times in a row, from 1968 to 1970. Bonallack would go on to become secretary of the R&A from 1983 to 1999, which effectively meant he ran The [British] Open among a multitude of other responsibilities.

For Campbell and Bonallack—both dynamic, well-educated, natural high achievers—the prospect of playing amateur golf and joining their respective family businesses was a lot more appealing than the grind of professional golf.

“In those days there was very little money in the professional game,” starts Bonallack, now 84 and enjoying retirement near St. Andrews. “If you turned pro the PGA [in the UK] would not let you take any prize money for two years. I would have had to have spent two years with a lot of expenses going out but nothing coming in. There was no European Tour at that time so all the pros were club pros and all tournaments had to finish on a Friday—even The Open—so the pros could go back to their clubs to look after their members over the weekend. It is very different now.

“As an amateur you can have a bad round and get away with it but as a pro you have to play very consistently to make money. You can’t afford to have a bad round.

Then there is the intensity of competing week after week after week.

“So the amateur game was very attractive. You could make lots of friends and the tournaments were nearly always at weekends. In the professional game you also have to do a tremendous amount of travelling and that didn’t appeal to me.”

With the irrepressible rise of professionalism in sports—which has seen the evolution of a tremendously entertaining and diverse, global industry—the amateur spirit has inevitably fallen back into the shadows. And as the careers of the amateur greats like Jones, Campbell and Bonallack illustrate, it is much easier to embrace amateurism when you know you have other means by which you can provide for your family.

As Tufts wrote in his Creed of the Amateur: “Amateurism, after all, must be the backbone of all sport, golf or otherwise.”

Perhaps it should, but it’s easier said than done.

Richard S. Tufts was president of the USGA and captain of the U.S. Walker Cup team. His grandfather, James Walker Tufts, established the Pinehurst Resort and R.S. ran the resort until the family sold its stock.

Dedicated to the amateur game, Tufts tasked himself with putting into words his interpretation of the amateur spirit, and his Creed of the Amateur has been immortalized on a bronze plaque by the first tee of Pinehurst No. 2.

“Amateurism, after all, must be the backbone of all sport, golf or otherwise. In my mind an amateur is one who competes in a sport for the joy of playing, for the companionship it affords, for health-giving exercise and for relaxation from more serious matters. As part of his light-hearted approach to the game, he accepts cheerfully all adverse breaks, is considerate of his opponent, plays the game fairly and squarely in accordance with its rules, maintains self-control and strives to do his best, not in order to win, but rather as a test of his own skill and ability. These are his only interests, and, in them, material considerations have no part. The returns which amateur sport will bring to those who play it in this spirit are greater than those any money can possibly buy.”

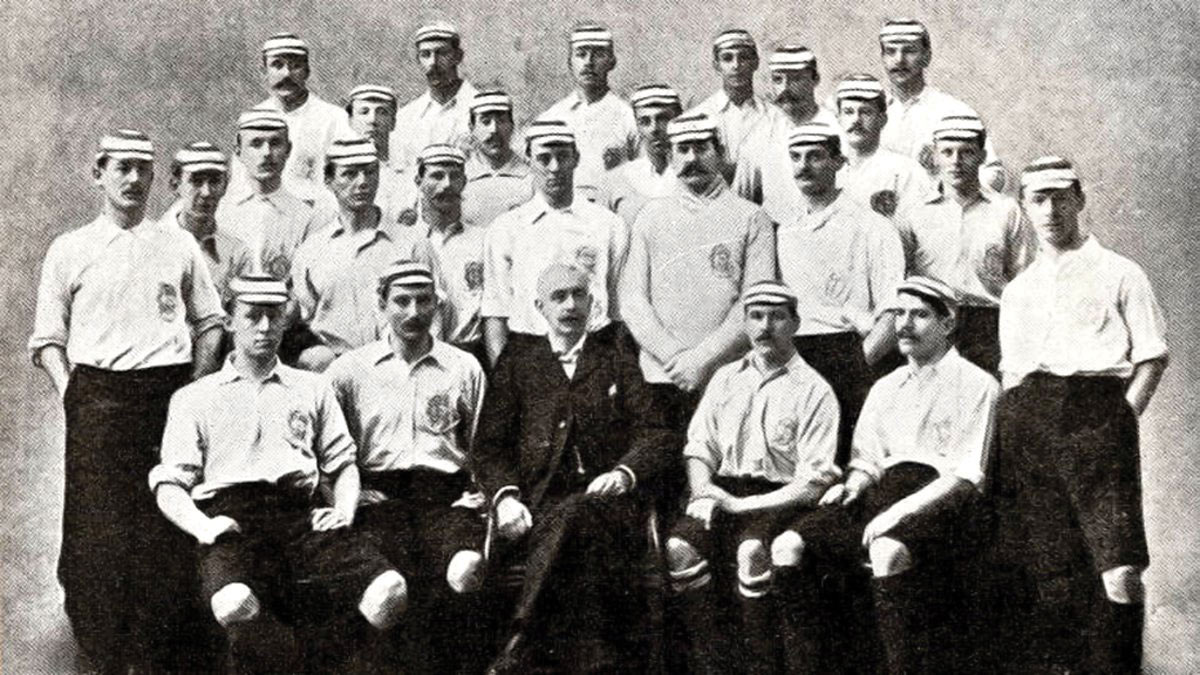

The Corinthian Football Club was established by Nicholas Lane ‘Pa’ Jackson in London in 1882 as a bastion of the amateur spirit to counter the rise of professional soccer. The name ‘Corinthian’ derives from the Greek city Corinth, but became synonymous with sportsmen playing for the sake of enjoyment, and so was adopted by a club that insisted sports should be played for enjoyment and personal betterment but not for profit.

Wrote Jackson: “He is one who has not merely developed his endurance by the exercise of some great sport, but has learnt to control his anger, to be considerate to his fellow men, to take no mean advantage, to resent as dishonour the suspicion of trickery, to bear a cheerful countenance under disappointment, and never to own himself defeated until the last breath is out of his body.”

Penalties were introduced to “football” in 1891 but Corinthian C.B. Fry objected, writing (in strongest Victorian terms): “[It is] a standing insult to sportsmen to play under a rule which assumes that players intend toe tip, hack and push opponents and behave like cads of the first kidney”.

While pragmatism dictated Corinthians adhere to universal rules, during a tour of South Africa in 1903, when the Corinthians team believed a penalty had been awarded against them unfairly, rather than try to save the spot-kick, the Corinthian goalkeeper stood to one side to allow an open goal.

Years later, when the Corinthians were awarded an undeserved penalty, the captain stepped up and gently passed the ball to the opposition goalkeeper.

The Corinthian spirit thrives in London to this day in the form of the Corinthian-Casuals amateur side, after Corinthians merged with the like-minded Casuals in 1939.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |