Much of sport’s fascination is its capacity to produce improbable climaxes. Just when you think it’s all over… it ain’t. That’s why we have to wait for the mellifluous warbling of the proverbial obese female before we know for certain who has won.

Because the mental element is so significant, a fast-disappearing lead heightens the tension which then increases the likelihood of the improbable happening. And because golf is essentially an individual sport, the mental pressure on the leader can’t be spread among teammates.

To win, you have to finish in front. But take the lead too early and you can be exposed for too long. Being a comfortable front-runner, like Tiger Woods for example, is a rare quality. A timely run on Sunday afternoon suits most people far more than trying to sleep for three nights on a slender lead.

So the combination of an anxious person protecting a lead and an uninhibited chaser with little to lose can produce precisely the right circumstantial mix for a final-day turnaround.

Often described as the greatest final round ever played in a Major, Johnny Miller’s stunning 63 to capture the U.S. Open at Oakmont in 1973 was quite extraordinary. Starting the day six shots off the lead and with 11 players in front of him, the 26-year-old Californian opened up with four consecutive birdies.

Propelled through the pack, Miller was now in contention and began to feel the pressure. “After the first four holes I got so nervous because I knew I was six back and the leaders would be gagging. I got a chance to win now and a shot of adrenaline went through me, and on 5 I left it short from 12 feet. At 6 I left it short from 10 feet and I three-putted 8 [his only bogey]. Now I’ve thrown away two or three shots and I went from being really nervous to sort of mad. I thought, ‘You got a chance to win the Open and you’re choking, you’re choking bad.’ That sort of fired me up again.”

After making the turn in 32 and a solid par at 10, Miller rattled off three birdies in a row and then another at 15. That got him to eight under. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Miller’s heroics was that he hit all 18 greens in regulation. “I didn’t even sniff missing a green,” he recalled.

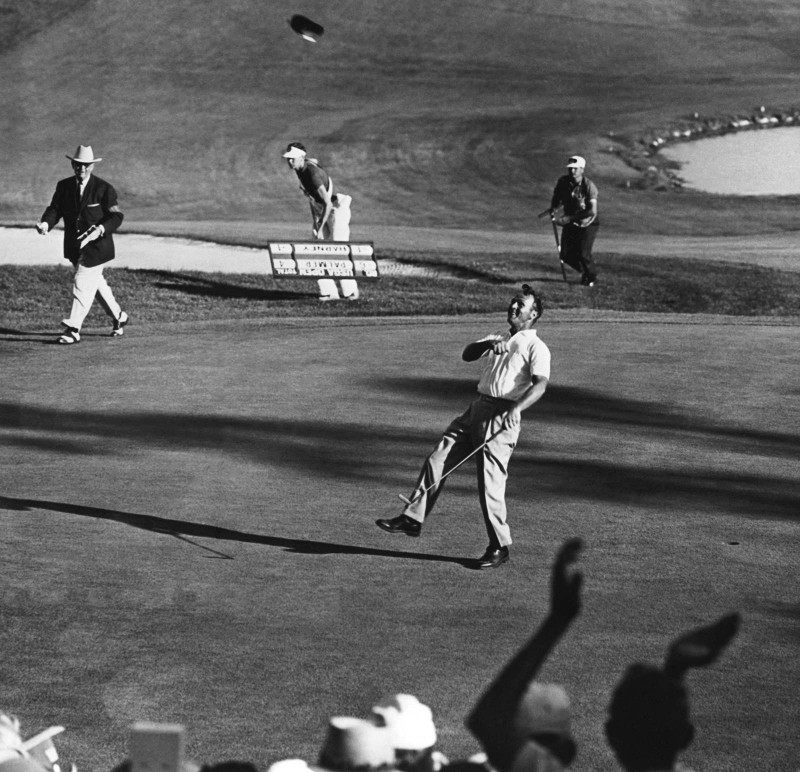

Another fabulous U.S. Open surge came at Cherry Hills in Colorado back in 1960. Solid if unspectacular rounds of 72, 71 and 72 left Arnold Palmer seven shots behind Mike Souchak. Just like Miller 13 years later, Palmer began his final round with four straight birdies. Two more at 6 and 7 helped him to an astonishing 30 at the turn.

But it was far from over with a young college kid called Jack Nicklaus and his playing partner, the veteran campaigner Ben Hogan, both in with a real chance. Souchak was still there or thereabouts. In the event, Palmer signed for a 65, at that point the best final- round score by a winner in U.S. Open history, to finish two clear of Nicklaus and begin what developed into a legendary rivalry.

It was the last of Nicklaus’s 18 Major titles at Augusta in 1986 that featured perhaps his most famous final-day heroics. They say the Masters doesn’t really begin until the back nine on Sunday, and it certainly roused the 46-year-old Golden Bear. Although he birdied 10 and 11, the real fireworks commenced at 15 when he hit his 204-yard approach to about 12 feet and then drained the putt for an eagle-three.

Two shots behind Seve Ballesteros, who was messing with the water on 15, Nicklaus stiffed his tee-shot at 16 to narrow the gap to just one. Seve bogeyed 15, Tom Kite birdied it and now there was a three-way tie at the top. Despite a wayward drive, Nicklaus hit his approach at 17 to about 18 feet. The photo of him with putter aloft after draining the putt has almost achieved iconic status. A textbook par up the last completed an incredible 30 shots for the inward half and he slipped into his sixth green jacket to become the oldest Masters champion.

Experience and knowledge of the course is clearly a huge advantage when playing amidst the dogwood trees and azaleas of Augusta. Gary Player was a grizzled veteran of 42 years and already a two-time Masters winner when he teed it up in front of the famous white clubhouse for the 21st time in 1978.

By his own very high standards, the South African began slowly, going round in level par for the first two rounds. A 69 on “moving day” lifted him up the leaderboard but he was still seven shots adrift of Hubert Green. But again the significant action didn’t begin until the back nine when Player birdied six holes on his way home to card a sensational 64. Once the dust had settled and Green had missed a putt on the 18th green to tie, Player finished one shot clear of Green, Tom Watson and Rod Funseth. It was his ninth and final Major triumph, and arguably his most impressive.

The biggest comeback in the PGA Championship since it switched from matchplay to strokeplay in 1958 came at Oakmont in 1978 when John Mahaffey shot a 66 to make up seven shots on Watson in the final round and then won a three-way playoff that also featured Jerry Pate.

Four other PGA Championships have seen the eventual winner prevail after starting the final round six shots back: Bob Rosburg in 1959, LannyWadkins in 1977, Payne Stewart in 1989 and Australia’s Steve Elkington in 1995.

Of course, heroic charges down the stretch have occurred in the [British] Open as well. As recently as 2012, Ernie Els overhauled a six-shot deficit to edge out the hapless Adam Scott. Poor course management clearly contributed to the young Australian missing out on what would have been his first Major title. But his mistakes shouldn’t detract from the Big Easy’s brave finish in what was the second largest final-round comeback in the championship’s 152-year history.

Also frequently remembered, perhaps more for the leader’s collapse than the eventual winner’s charge, was the greatest final-round comeback of them all, at Carnoustie in 1999. Paul Lawrie was a seemingly hopeless 10 shots off the pace when he teed off on Sunday afternoon. Frenchman Jean Van de Velde had led from the halfway mark, was five shots clear going into the final round and still had three strokes in hand as he drove up the last. Catastrophically, he then recorded a triple-bogey seven that plummeted him into a three-man playoff alongside Lawrie and Justin Leonard, the 1997 champion.

Local man Lawrie had earlier shot a remarkable 67, a superb score in inclement conditions and on a brutal course with rough so thick it was causing many of the field to lose their sanity as well as their golf balls. In the four-hole playoff, Lawrie birdied 17 and 18 to win comfortably, but the feeling persists that the Scot never really received the credit his final-round charge deserved.

Perhaps the horror of empathizing with a defeat snatched from the jaws of victory really is a more powerful emotion than the thrill of witnessing a dramatic and brilliant come-from-behind victory. Either way, it always makes for a good story.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |