There are those who believe a golfer may be defined by statistics. They are, of course, wrong.

Severiano Ballesteros may have won 88 times as a professional (actually, technically, he never was an amateur), lifting five major championships in the process, but to reflect on his career and his impact on the game via the detail of his on-course achievements would be to miss the biggest of points.

His death at home on May 7, 2011 at the age of 54 robbed us not just of a golfer who was one of the most exciting players of our lifetime but, more importantly, it takes away far too early a much loved and valued human being.

It was his emergence as a 19-year-old when he tied for second in the 1976 [British] Open at Royal Birkdale that trumpeted his arrival on the global sporting scene and triggered the growth that the European Tour has enjoyed ever since.

Impossibly handsome with a smile that lit up any room, dynamic and aggressive in the way he played, instinctive in the rapport he enjoyed with galleries, indeed with everyone who passed before his all-seeing eyes—these inate qualities forged his reputation and helped to establish a unique relationship with the sporting public all over the world. He touched people in a special way, even those who instinctively view golf as an arcane form of tedium.

That Seve was a truly great player is beyond any doubt but it was his progress through golf’s upper echelons as a man—his bravado, his buckling swash, his instinctive derring-do—that dances deliciously in the memory of those of us fortunate enough to have known him at the peak of his powers.

Put simply… To appreciate Seve, you had to be there. If you were, then you would never forget the experience. Men wanted to be him, women wanted to be with him. Suddenly the staid world of European golf had a genuinely sexy hero. What Arnold Palmer had done for golf in America, Seve did for Europe.

Before the 1980 Masters, I watched from the clubhouse at Augusta National as he finished a practice round, several thousand fans embroidering the scene. It took him ages to navigate his way through the throng to the clubhouse and when he finally made it he looked at me and grinned hugely. He held out his hand and when I held out mine he dropped several scraps of paper into it and laughed. Each scrap contained a girl’s name and a phone number. “These people are crazy, eh?” he said. His English was rapidly improving by then.

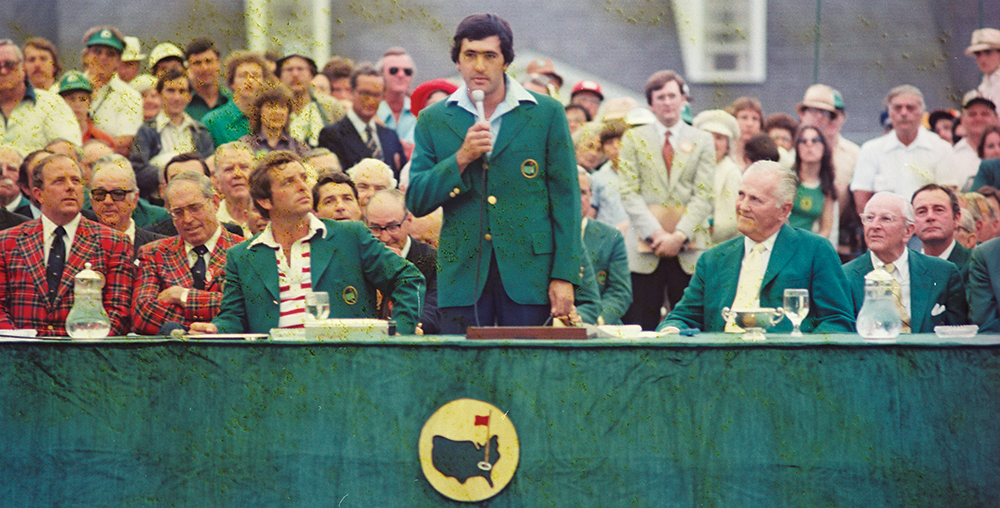

When he won his first Green Jacket a few days later, an instant invitation came for the nine British journalists present that year to join him that Sunday evening at his rented house for a celebration party. We arrived before he had returned from various duties at the club. There were maybe twenty people in total present, most were part of his Spanish entourage. Two stunning-looking young women weren’t.

When he turned up Seve was wearing his new club blazer, a white shirt and an Augusta National member’s tie. I have never seen anyone look happier or healthier.

If he’d been a Labrador his nose would have been dripping. At 23 he was king of his world. When I mentioned something along these lines to him his face darkened and he asked me to follow him. We moved into the kitchen where the connecting door to the garage had been removed and replaced by a trapeze.

“See this,” he said. “I must hang upside down from this for 20 minutes each morning to try to stretch my back. Every day I have pain. Healthy? No, not healthy.” And he made me try it for a few minutes. A few minutes was all I could stand. Even in the earliest days of his success, Seve knew that, for him, a long career was almost certainly out of the question. The fact is that he never played totally pain-free. Another fact is that opponents never realized this.

Like Tiger Woods now, his default position was never to show any weakness if he could help it.

Nowhere was this more apparent than at the moment of his [British] Open victory at St. Andrews in the high summer of 1984.

This was the second of his three Open wins but in so many ways the most glorious. Sun blitzed the Old Course that week and Seve blitzed the old girl even more.

![The happiest of men: Seve after winning the 1984 [British] Open at St. Andrews](https://kingdom.golf/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Seve-at-the-1984-British-Open.jpg)

When Sunday’s play started he was two shots behind Tom Watson and also trailing Bernhard Langer. That day, the American and the German played last with Seve in full flow immediately in front of them—an irresistible tidal wave of Spanish ambition, passion and belief.

Inevitably, as ever at this special place, it all came down to the final two holes. Seve parred the 17th and then conjured up a birdie at the last, his putt from around 12ft hesitating before bending to his intense will and toppling into the hole for a score he immediately knew would win the day.

His reaction was electrifying. Draped in his favorite blue sweater and trousers, white shirt and deep tan, he transformed into a man who was literally beside himself with joy, punching the hot air as he hopped a full 360 degrees on the moonscape that is the 18th green at this cathedral of the royal and ancient game.

Behind him on the 17th, Tom Watson heard the commotion, glanced briefly at the scene and then dropped the shot that assured Seve of victory. Watson was going for his sixth Open title and his third consecutive victory, but Seve’s flair broke the spell for the American.

Now the spell is broken for all of us who admired him. His collapse at Madrid Airport with what turned out to be a brain tumor in the fall of 2008 changed everything for him—and in its sad way for us too.

His determination to survive a series of punishing operations was as typical as so much of his play. No one ever, ever, ever has refused more impressively to concede defeat, whether on a sports field or in the harsher environment of life itself.

His Lifetime Achievement Award during the 2009 BBC Sports Personality broadcast was as emotional as it was deserved. His protege, Ryder Cup pal and lifelong friend Jose-Maria Olazabal did the honors at the Ballesteros home in Pedrena on Spain’s rugged northern coastline.

![The car-park champion cruises to victory in the 1979 [British] Open at Lytham](https://kingdom.golf/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/seve-1979-British-Open.jpg)

Olazabal struggled to get through it, his eyes welling with tears. Back at my own home I cried too. What the television audience did not see was that when the short ceremony was over Olazabal collapsed to the floor and Seve was cradling his friend to comfort him. Since then, however, Seve struggled, often alone and sad, at his home overlooking the sea at his beloved Pedrena.

We first met in a Southport restaurant 48 hours before the first round of the 1976 Open. He spoke little English then but I remember we shook hands and argued amiably about whether his beloved Barcelona football team was better than Liverpool. I wished him luck and we went our separate ways.

Six days later he tied with Jack Nicklaus for second place and Lee Trevino came whooping into the press tent to tell us we had just witnessed the arrival of a genius. That was kind of Lee but, actually, unnecessary as even a near-blind man could see that fact for himself.

Soon after, Seve and I became friends, traveling to the world’s tournaments together, laughing together, drinking together, often arguing together. Like all the best relationships it was a tempestuously satisfying one. He could be quick-tempered, brusque, occasionally paranoid, obtuse and frustratingly stubborn. He had a fine sense of self and what he was, but he combined this with an instinctive grasp of appropriate humility and, always, his charm and charisma overwhelmed everything else.

Mind you, Seve was one of life’s great complainers, absolutely world class. He always had something to moan about. If he didn’t, he made it up. Like John McEnroe in tennis, he fed off perceived slights. Even the United States was on his whinge list—from being announced on tees as “Steve” Ballesteros to the way the media portrayed him as some lucky, hick Spaniard who had won his first [British] Open title at Royal Lytham & St. Annes in 1979 despite slicing his drive into a car-park. He had a point because the fact that he then finessed his ball on to the 16th green and holed the birdie putt seemed to have escaped the media’s notice. It was a resentment that helped fuel him when playing for Europe in the Ryder Cup.

Sometimes, the dark moods Seve was prone to came between us. Such a moment came in the mid-1980s in Dublin at the Irish Open—he won three of these coveted titles and was happy to be known as an “honorary Irishman.” By then Seve was the most in-demand golfer in the world. He was also in full combat mode when it came to his relationship with the PGA Tour and its commissioner at the time, Deane Beman.

Beman had been a very decent player himself with four Tour victories before becoming the boss. He was as abrasive and determined a character as Seve himself and when he decreed that “foreigners” must commit fully to the American circuit if they wished to play, that they entered at least 15 events and that they must request permission to return, in Ballesteros’s case, to Europe, Seve went ballistic.

That row was on-going at this particular Irish Open. What made things worse for Seve was that Beman, on holiday in Ireland at the time, had been invited by the organizers to play at Portmarnock. Seve came in for a pre-tournament press conference and soon declared his opposition to such a move. “Beman is taking a place that should be reserved for a player who needs the money. He should not be here,” he said. I decided to follow up this thought and when he exited the media center I walked with him and asked about Beman, the PGA Tour and how he felt.

His reaction was as startling as it was dramatic. He stopped, glared at me, his face contorting in rage as he asked why I was asking him such questions. “Deane Beman?” he snorted. “Deane Beman? Why you ask? You are trying to upset me. I don’t want to talk about this man. I think of him when I go to sleep and I am still thinking of him when I wake up.” As he said this last bit his right fist curled and he pulled his arm back. I thought “Christ, he is going to hit me.” The security guard with us thought so too and obligingly stepped aside to allow him a better swing. Then Seve’s arm relaxed and he turned swiftly and strode away muttering.

That, I thought, was obviously the end of our friendship. The next day after his round he was back in front of the reporters again. I sat at the back, sulking and determined not to ask any questions. After twenty minutes or so the interview was over and I stood up to walk out. It was then that Seve, speaking urgently, said “Beel, Beel, we must speak. Please.” Reluctantly I turned back. He grabbed me by both arms and moved close so only I could hear what he was saying.

What he said was: “I want to say sorry for yesterday. I should not have spoken to you like that and acted as I did. But Beman upsets me, you know. I was wrong and I am sorry.” He offered an embrace and I accepted. Who wouldn’t? Now, though, I felt sorry for him and so I said something about my wife speaking to me all the time like that. His face grew more serious and he moved in close again. “That is okay for your wife but not for me. Never for me.” We ended up laughing together like two schoolboys lost in their own naughtiness and our friendship never looked back after this incident.

Despite his evident fire for the European Ryder Cup team, many of his closest friends and strongest admirers were American. Arnold Palmer, with whom Seve has so often been compared, has particularly fond memories of the Spaniard. “He was just a child—54 is awfully young to pass on,” he reflected, sadly. “I knew Seve well and enjoyed his company. He was a pretty outgoing and flamboyant person. He was a great tribute to the game of golf and more specifically to the Ryder Cup. He really put a spark into the European golf community and the record there proves itself. He will be missed.”

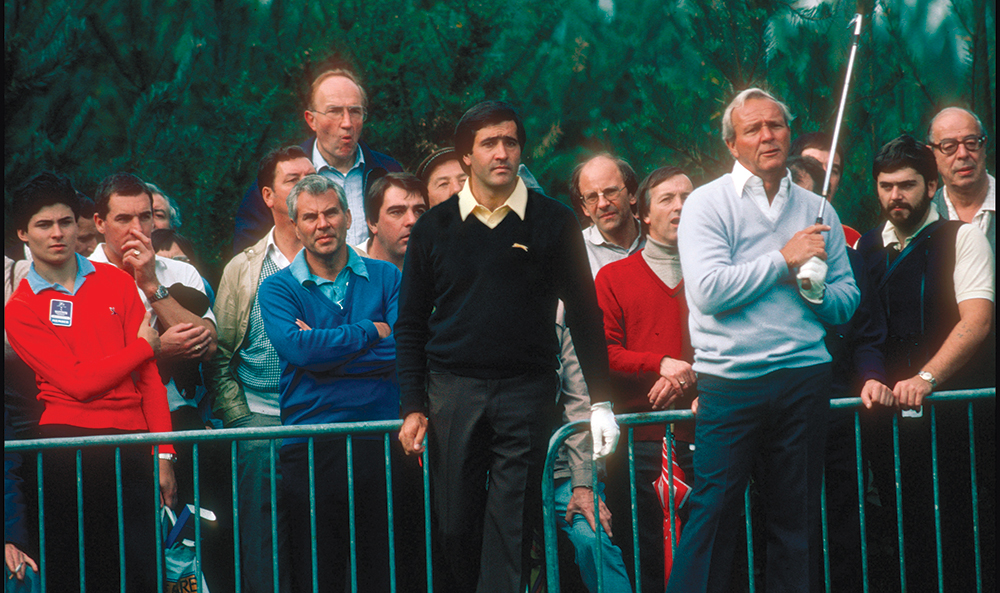

Mr. Palmer has a particularly vivid recollection of a fantastic match between the two of them in the 1983 World Match Play Championship at Wentworth when Seve staved off defeat by pitching in at the 18th.

“I had really pretty much wound up my career at regular tournaments at that stage, but when they asked me to play I thought, well, what the heck,” Palmer recalls. “I’d won there a few times and decided it would be fun. As it turned out I was 1-up on Seve on the 18th hole and he was in the woods and I was on the front of the green. He pitched it in out of the woods for a three and I missed my three and he beat me in a playoff on the first [extra] hole. I’ve seen strange things happen on the golf course and that was one of them. But I’ve had the reverse happen a few times in my favor, too!”

For me, as for all his friends, the last couple of years have been hard to witness even if he told us not to feel sorry for him, that he had “enjoyed a brilliant, fantastic life.”

Typically, my old friend was determined to rage, rage and rage again against the dying of the light. He succeeded in this rage but eventually the cancer was too much even for his spirit, just as his brittle spine prematurely ended his golfing career.

But while he was alive and well and playing brilliantly the world for many of us was, for a time, a better, brighter, more fun-filled place. Vaya con Dios, Seve. Gracias, Amigo.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |