Doc Giffin worked as a reporter on the Pittsburgh Press newspaper and as press secretary for the PGA Tour before accepting the role as Assistant to Arnold Palmer in 1966. It was a job he fulfilled for the rest of Palmer’s life, for more than 50 years. Here Giffin reflects on Palmer’s natural flair and inimitable manner in dealing with the media

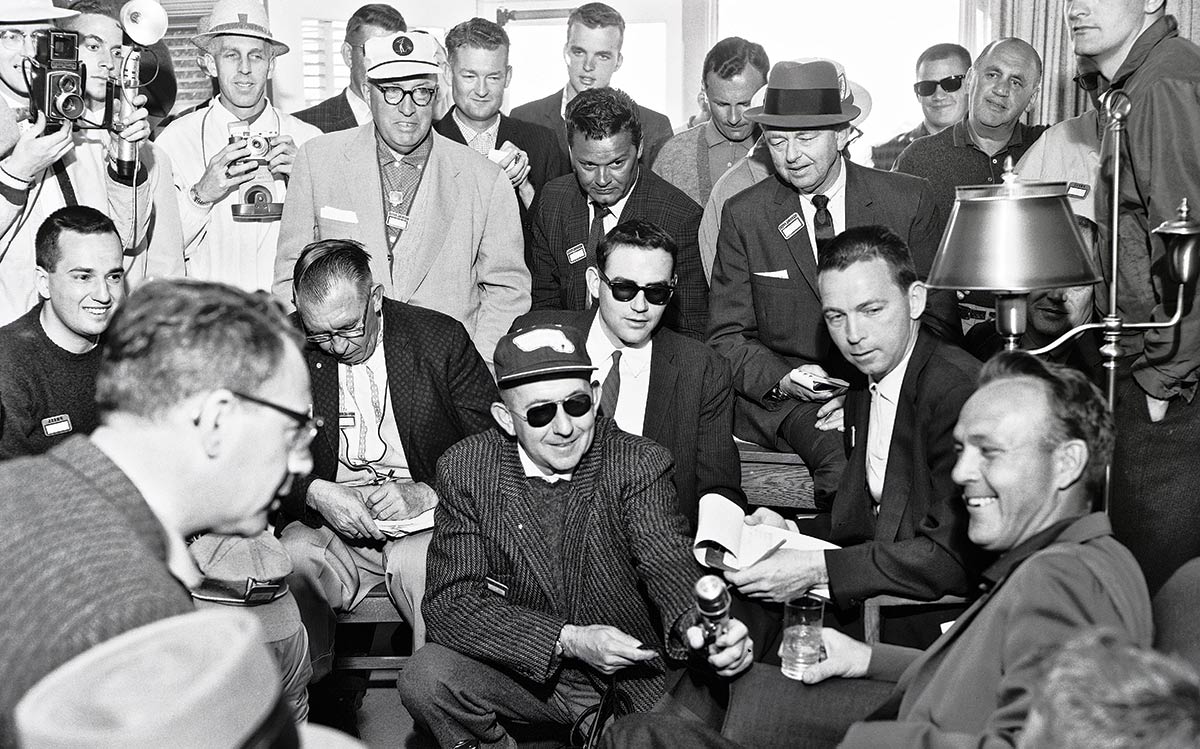

Anguish enveloped the face of the college radio reporter. He had just finished an interview with Arnold Palmer at the end of a long post-round pressroom session at the Western Open in Chicago in the early 1960s and realized he had forgotten to hit the record button. He had nothing on tape. No problem. This was Arnold Palmer. Rather than express annoyance or walk away, as many people of his stature might have done, Arnold simply had the flustered young man turn on the recorder and they re-did the interview. That relatively insignificant moment is a microcosm of Arnold Palmer’s lifetime with the media. Willing. Accommodating. Understanding. Admired.

I feel qualified to say this, having spent more than 50 years on the inside as Arnold’s personal assistant and media representative. He was a remarkable athlete and celebrity, willing and almost anxious to deal with the demands of the media that came with his exalted position. That attitude remained with him all his life. Admittedly, I did a little filtering, but he rarely turned down an interview request that I brought to him and they were not always in the most comfortable of circumstances. Nor did he often complain when an occasional one didn’t go too well.

I got vivid evidence of his understanding of the media’s role even before my work for him began. I was in my first year as press secretary on the PGA Tour when he won the Texas Open for the third year in a row, in 1962. In those days he was still doing his long-range traveling on commercial airliners and he faced a tight squeeze to make his flight after he won that Sunday afternoon. Rather than kiss off the normal post-victory press conference, though, he said, “I’ll just catch the next flight,” and headed for the media center. He knew what it meant not only to the press but also to the tournament and its sponsors.

Noted British golf journalist Donald Steel once observed: “He always said he realized the press had a job to do and it was his duty to help them do it.”

More recently, Doug Ferguson, who has covered golf for Associated Press in noteworthy fashion for 20 years, said: “Arnold remains the model for a relationship with the press. I always felt the greatest trait of Arnold was that he made everyone around him feel important, and that was particularly true with the press. Even someone asking an awkward or pedantic question was treated with respect.”

Marino Parascenzo, long-time golf writer at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, recalls a locker room incident early in his golf-writing days after Palmer shot 81 and missed the cut in the 1976 Masters: “I really didn’t want to have to ask the great Arnie Palmer about shooting 81, but, as a journalist, you have to. Four or five other writers felt the same way. We were lined up in front of a dejected Palmer, slumped over in front of his locker. After an embarrassing spell of silence, one of the writers delicately said to him, ‘We hate to have to talk to you at a time like this.’ Arnie looked up and replied, ‘Fellas, we talked when times were good, we’ll talk when times are bad’.”

Parascenzo and other Western Pennsylvania writers who covered the golf beat in more recent times, as well as a large number of local TV and radio sportscasters, relished their opportunities to talk to Palmer, who always made sure to take care of the media reporters from his home area and around his winter residence in Orlando, Florida.

Says Gerry Dulac, who succeeded Parascenzo at the Post-Gazette and has covered the game for 28 years: “What I have come to realize about my time around Arnold Palmer was not necessarily the moments I enjoyed as a professional interviewing and writing about the man who changed the way golf was viewed around the world. Instead, it dawned on me how easy it was to take his immense presence for granted because of how easy he made everyone around him feel.”

To get some idea of why Palmer got such great press coverage almost universally throughout his career—and looking beyond his innate warmth toward people of all ilks—you have to go back to his days at Latrobe High School when he was dominating junior golf in the area. His exploits were well-chronicled in the home area and in Pittsburgh’s three daily newspapers at the time, but one writer took particular interest in the young man and became fairly close to him and his family as he started piling up victories in the area’s top scholastic and amateur tournaments. That man, who went on to gain considerable acclaim himself in the world of golf, was the bombastic and irrepressible Bob Drum, the quick-witted scribe of the then-existing Pittsburgh Press.

Drum was the first writer to foresee the stardom that was to come years later for Palmer and counseled him about the importance of befriending and co-operating with the national and international press. Years later, as Palmer followed Drum’s advice and became the game’s most-popular hero, Drum loved to brag in one of his uniquely-exaggerated bellows: “Arnold Palmer? I invented Arnold Palmer.”

That master of acerbic one-liners had a role in what was perhaps the finest hour of Palmer’s astounding career, at the 1960 U.S. Open Championship at Denver’s Cherry Hills Country Club. The story of Arnold’s remarkable final round has been told over and over with slight variations, but the gist of it was this:

Palmer, who had won his second Masters two months earlier, had his problems during the first three rounds. As he grabbed a quick hamburger in the company of Drum, the incomparable Dan Jenkins and a couple of the other competitors before heading out for the final 18 holes, he was 13 players back and seven strokes behind leader Mike Souchak. Still, having made 12 birdies already, Arnold felt he could win the tournament. “What if I shot 65? Two-eighty always wins the Open,” Arnold mused aloud. Rather than offering encouraging words, though, Drum shot back: “Two-eighty won’t do you one bit of good.” Teed off no end by that response, Palmer stormed out, drove the first green, something he had failed to do the three previous rounds, birdied it and five of the next six holes, shot the 65 and 280, right on the button, to win his first and only U.S. Open.

The press had a part in what followed Cherry Hills that summer, too.

Despite his locker-room barb, Drum remained close to Palmer and was a member of the small entourage of family and friends that left within days for Ireland and the Canada Cup (later renamed the World Cup) and on to Scotland for the Open Championship at St. Andrews. On the flight over, Arnold and Bob got to talking about Bobby Jones’ historic Grand Slam—the U.S. and British Opens and the U.S. and British Amateurs—a feat that almost certainly will never be matched. That’s when Palmer came up with what is now known as the modern or professional Grand Slam—the two Opens, the Masters and the PGA Championship. Drum knew a good idea when he heard one and at the Canada Cup and subsequently at St. Andrews sowed it among the members of the international press. Thus, golf had that target of excellence that remains unreached to this day.

It was during the week at St. Andrews—when Palmer nearly won the third leg of that feat—that he gained the admiration of not only the golfing public of the British Isles but also of the complement of fine writers who covered the game for the British press, respected men such as Henry Longhurst, Pat Ward-Thomas, Peter Ryde, Leonard Crawley, to name just a few.

Palmer provided a foreword for Forgive Us Our Press Passes, a book published by their Association of Golf Writers, in which he wrote: “I always seemed to get along with the press and I counted many writers as friends. Then, in 1960, when I crossed the Atlantic for the first time to play in the Canada Cup and the Open Championship at St. Andrews, fulfilling a life-long dream, I met a whole new battery of golf writers who were unique and singularly charming and treated me wonderfully.”

Arnold’s exploits and personality played an important role in the explosive growth in popularity of the game in the latter half of the 20th Century, but they also give proper credit to the expanding attention national television gave the sport. The crowning touch in that regard came in 1995 when Palmer, the player, hopped over the fence and became Palmer, co-founder of Golf Channel, which now airs to some 200-million homes in 84 countries around the world.

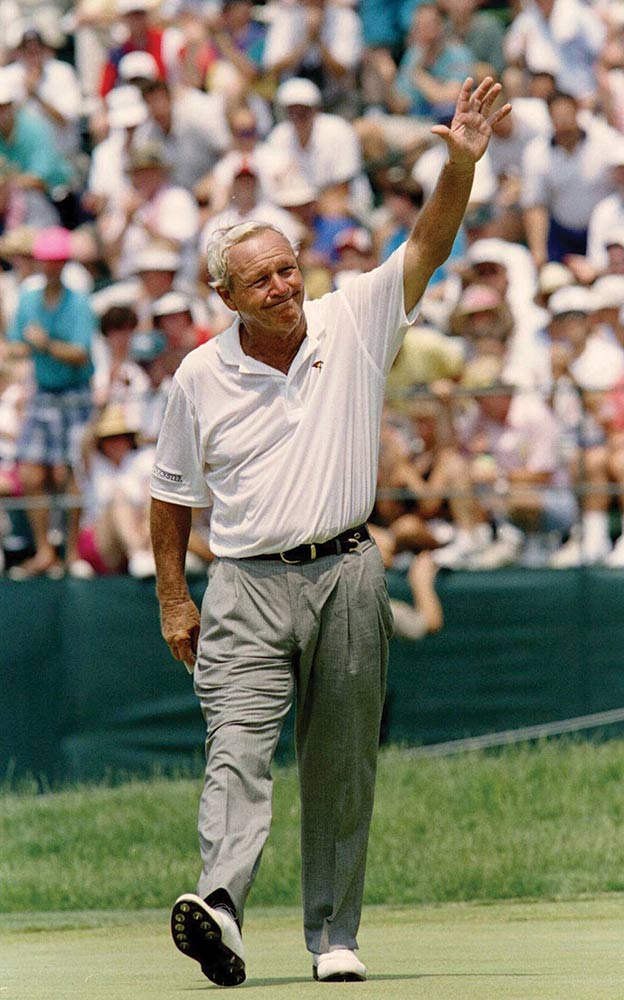

Of all of his significant achievements during his lifetime, Palmer ranked the creation of Golf Channel at the top of the heap, just as he felt, at age 65, the final moments of his last U.S. Open in 1994 at famed Oakmont were the most memorable and heartwarming. Again, it was a media-driven circumstance.

An emotional man by nature, he had been overwhelmed by the reception of the galleries all day and particularly as he played the 18th hole in his final competitive round at a course he first played as a teenager. He had a hard time maintaining his composure in a TV interview after holing out and when he met with the assembled press in the media center afterward. It is not unusual for the press to applaud the winners of tournaments when they arrive for the obligatory, post-victory interviews. That afternoon, though, when Arnold, sobbing into a towel, rose to leave after struggling to control his emotions as he talked about the finality of the day, the room exploded with applause.

That was unprecedented… just as he was.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |