Paul Trow writes that putting is a confluence of art, science and fortitude, but a successful putting stroke is as elusive as it is prized, no matter how much time golfers spend on the practice green, putting on a strip of carpet in the basement, receiving tuition or how much they spend on the latest game-changing putter

They call it a game within a game. But to elite golfers it’s far more than that. It’s the difference between success and failure. In a world where everyone habitually drives 320 yards and pitches to within a few feet of the pin, only the finest of margins separates the superstar from the also-ran.

That dividing line is, and always has been, the flat stick. There’s nothing new about the search for golf’s Holy Grail—a putting stroke that works. But like the biblical original, this quest remains in perpetuity both elusive to mere mortals and in the sole gift of the gods.

The deities, by whose whims we must all abide, are in this case the Royal & Ancient Golf Club and the United States Golf Association.

Their tablets are the Rules of Golf, and their mindset is to preserve the game’s innate difficulties. Any relief provided by advances in technology or technique is routinely cancelled out by technicality.

In the 1960s, Sam Snead, though past his prime, still played superbly only to be let down time and again by his frailties on the green. The dominance then enjoyed by the Big Three—Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus—hinged more than anything on their precocious putting jabs. After the usual preamble, these assassins would step up, take a couple of cursory glances, and pull the trigger.

Pop, the ball would jump up; thud, it would hit the back of the cup; rattle, it would drop with a swirl. Simple as that!

Except for poor old Sam, such gusto was but a distant memory. During the 1966 PGA Championship at Firestone he double-hit a two-foot putt and in desperation changed his style mid-round. According to playing partner Billy Farrell: “On the very next hole, it’s Sam’s turn to putt and this time he straddles the ball, he goes croquet style.” It worked and he stuck with it for the rest of the tournament en route to a share of sixth place.

After a winter of hibernation and honing, Snead began 1967 by winning the PGA Seniors’ Championship by nine strokes at PGA National and tying 10th in the Masters.

But it didn’t take long for his croquet method to come under scrutiny.

The USGA and the R&A met just before the Walker Cup in England and decided to outlaw it from January 1, 1968 (Rule 16-1e). Joe Dey, the USGA’s executive director at the time, said: “We felt it was the only way to eliminate the unconventional styles that have developed in putting. It was some other game—part croquet, part shuffleboard and part the posture of Mohammedan prayer.”

Far from downhearted, Snead insisted: “I might be able to alter my stance and still putt my way.” And he did just that by improvising a sidesaddle stance and swinging the putter through the line towards the hole in the style of slow-motion ten-pin bowling. Aged 62, Snead putted sidesaddle to finish tied for third in the 1974 PGA Championship at Tanglewood Park. Appropriately, this feat and the implement with which it was achieved are enshrined, along with his trademark pork-pie hat, in the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Interestingly, hardly any golfers, professional or amateur, emulated sidesaddle Snead, testimony perhaps due to its difficulty when attempted by ordinary mortals.

The only comparable intervention by the authorities since came on January 1, 2016 with the controversial ruling against anchored putting strokes. If the idea was to banish the long putter, then this change to Rule 14-1b can only be branded a partial success. In reality, few club golfers used the method anyway, again largely because they lacked the skills. And many of the high-profile exponents of the broomhandle—think Webb Simpson, Keegan Bradley and Adam Scott—continue to use it, albeit unanchored, or so they believe and maintain.

These players are still thriving on the short grass, though possibly not to the extent of half a decade ago. Inevitably, all sightings of long putters are accompanied these days by mutterings from rival competitors that anchors are far from away.

The two leading lights on the Champions Tour—Bernhard Langer and Scott McCarron—similarly come under this grudging spotlight each time they are in contention. Both are adamant they have adjusted their methods and are operating within the law.

Langer, just four victories shy of Hale Irwin’s record tally of 45 on the PGA Tour Champions, is surely the go-to lab rat for students of putting and its innumerable vicissitudes. In many respects, the 62-year-old is the modern equivalent of Snead. Both players struggled with the yips and overcame them through radical surgery. The difference between them is that Langer was 30 years younger than Snead when first afflicted.

In his case, the slow, mossy greens on which he learned his trade in Bavaria back in the early-to-mid 1970s were the diametric opposite of the putting surfaces he would encounter on tour. At that time, a combination of Bermudagrass, creeping bentgrass and Poa annua was becoming the norm on championship greens and required a more delicate touch than a generation previously.

As Langer began to rise up the world’s leaderboards the long putter wasn’t even a twinkle in the German’s piercing blue eyes but he knew that drastic measures were required if he was to putt efficiently enough to come near to fulfilling his prodigious talent.

Not possessing the exquisite touch of contemporaries Ben Crenshaw and Seve Ballesteros, he would always have to rely on mechanics to narrow the gap. He knew most errors stemmed from movement in the wrists, so he turned his left arm into a rigid extension of his putter and pivoted only from the shoulders. All seemed well for a while, most emphatically in 1985 when he collected his first Green Jacket at slippery, undulating Augusta National.

But the demons soon returned to haunt his otherwise immaculate game, so it was back to the drawing board. “I had to take my wrists out of the putting stroke completely. That’s why it didn’t work in the long run, because there was still movement in them,” he told me shortly after winning the Masters for a second time in 1993. “I had to do something as I couldn’t have another year like 1988.”

But instead of abandoning his method, Langer turned it almost into a self-parody. His left hand crept further down the shaft and the right gripped the club and left forearm like a brace. The honeymoon didn’t last and by 1997 the broomstick had flown into Langer’s bag where it has resided ever since. To be fair to Langer, he experimented with his old left-hand-below-right method and also with the claw grip and left forearm vice, favored respectively by Phil Mickelson and Matt Kuchar, as D Day for anchoring approached, but neither worked.

Despite his travails, it’s a fair bet Langer is too cultured to have ever been tempted, as the famously irascible 1958 U.S. Open champion Tommy Bolt once was, to tie his putter to the back bumper of his truck as punishment for misbehavior as he drove to the

next tournament.

From the 16th century to the 19th, golf was played with wooden-headed clubs and ‘featherie’ balls. The putter, or ‘putting cleek’, had a face fashioned from a hard wood like beech and a shaft made of ash or hazel.

In 1848, the more durable gutta percha ball was introduced, made from the rubbery sap of a tropical tree, triggering the arrival of iron-headed putters that delivered improved accuracy and feel. A typical putter from the late 1800s would comprise American hickory wood shafts, grips of padded sheepskin, and thin, bladed heads made of brass.

Despite gradually divergent production methods, it wasn’t until the 1930s that an individual putter acquired celebrity status—when Bobby Jones completed his ‘impregnable quadrilateral’ of Grand Slam titles in 1930 with a wand known as Calamity Jane II. Measuring 33½ inches in length with a goose-necked design, 8 degrees of loft on an offset blade and a hickory shaft, the original Calamity Jane was made in Scotland around 1900. When it became too worn, replacements were commissioned from Spalding, one of which is now on display at the Arnold Palmer Center for Golf History in Far Hills, New Jersey.

Steel shafts, introduced in the late 19th century, were officially legalized by the R&A in 1929 after being made fashionable by the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII), and remain the standard fit to this day. The next R&A intervention came in 1951 with its approval of center-shafted putters. Previously, the shaft was attached close to the heel, as with all other clubs. Consequently, a variety of bent and offset shafts have since come into vogue.

Seeking tempo, John Reuter, a teaching pro from Phoenix, Arizona, came up with a putter that “swung like the pendulum of a clock” in the late 1940s. Reuter’s first models, ‘the sweet strokers,’ were adapted and given a new name: Bulls Eye. Lou Worsham won the 1951 Phoenix Open with it and a few years later Reuter teamed up with Acushnet to mass produce the Bulls Eye. Made from soft brass for feel at impact, with a fluted shaft, the Bulls Eye has stood the test of time, spawning many worthy copies along the way, including Scottish brand John Letters’ iconic Golden Goose.

In 1959 in his garage in Redwood City, California, Norwegian-born engineer Karsten Solheim invented the Ping putter—named for the distinctive pinging sound it made when the ball was struck. After moving to Phoenix, he created the Anser putter in 1966 (the ‘answer’ to putting, according to his wife Louise) and soon had a hold on the market. In the 1980s, 26 of the 40 men’s Majors were won by golfers using Ping putters, and at the last count the brand had secured well over 500 tour victories.

Technological advances have revolutionized all clubs over the past four decades, but with putters the changes were made almost exclusively to the head.

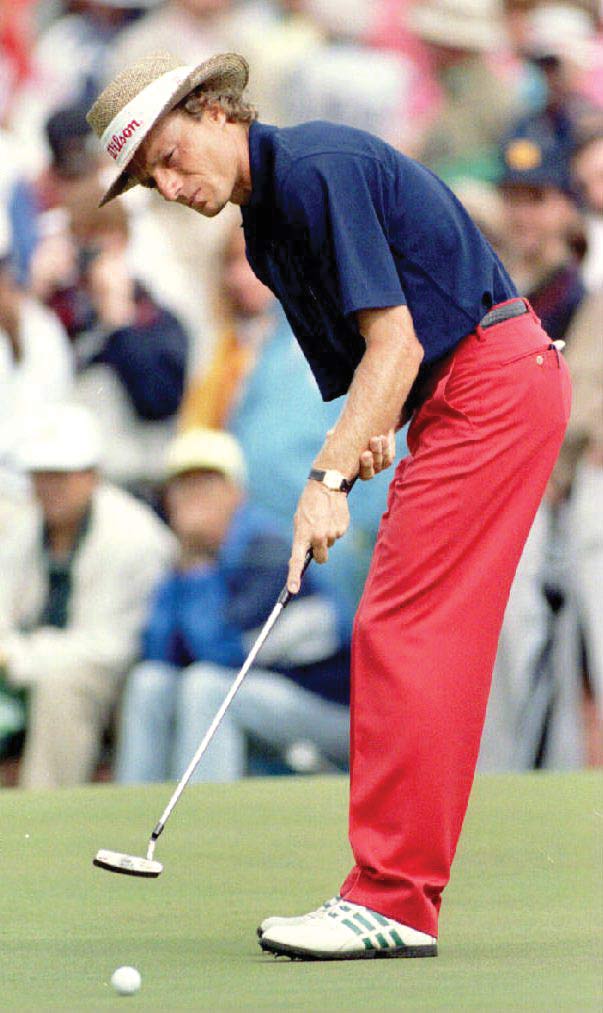

When Jack Nicklaus won the 1986 Masters at the age of 46, he did so brandishing a Clay Long-designed MacGregor Response putter with an oversized milled head and cavity back. Not surprisingly, sales figures sprang from the previous year’s doldrums to an estimated 350,000.

The next striking innovation was the Odyssey 2-ball putter from Callaway which dominated the market in the early 2000s, when balata balls reigned supreme. Like the Bulls Eye, it was much imitated.

Nowadays, the market is more diverse than ever. Putters, from a generation of talents like Scottie Cameron, Bob Bettinardi and Austie Rollinson, run the gamut from conventional blades to mallets to wild-looking heads that feature a variety of attachments and inserts. These inserts are intended to deliver a soft contact and prevent the head from twisting even if the strike misses the center.

Since prize-money became the main issue for tour pros, demand has rocketed for putting coaches who can deliver results—from George Low, Jr., who influenced Palmer’s methods during his prime, to modern-day luminaries like Dave Pelz and Brad Faxon.

Truth is… their worlds were entirely different. Low’s mantra, having been raised on slower greens, was to keep your head down and commit to the line while Pelz and Faxon believe in tracking putts, hit with top-spin on the upstroke, on slick surfaces with borrows determined not just by topography but grain and grass type as well.

In their world, there is now much more to analyze—hence the recent arrival of green-reading books replete with contours and 3D profiling. The silky strokes of U.S. Ryder Cup stars Steve Stricker and Rickie Fowler are glowing examples of the efficacy of this approach.

Gary Player still relishes the halcyon days of Jabberwocky. “When I hear commentators say it was a bad putt because he jabbed it, I don’t know what to think,” he said. “It’s debatable if Tiger or Bobby Locke was the best. Locke? He was a jabber. [Billy] Casper? Big jabber! Casper had his hands fixed and he chopped it. Look at [Brandt] Snedeker. Take out the unnecessary movement. The average player? There’s so much movement in the putting stroke, they’re spaghetti wobblers. It’s still [all about] a good eye and great feel. Putting and the mind win golf tournaments.”

This dogmatic view lacks the nuances enunciated by comedian and golf enthusiast Larry David. “I have four styles of putting,” admits the man behind Seinfeld. “The long putter will work for a round or two, then I move to side-saddle. That will work for a while, then I switch to a regular-length putter. Then my last resort is looking at the hole instead of the ball. You have to keep rotating the system and be ready to switch the second things stop working.”

For the befogged tour pro this will obviously not do. Too much hangs on every putt and the tension seems inescapable. But perhaps David’s multi-faceted approach can at least ease the pressure on some of us, maybe even elicit a chuckle. After all, it is only a game, within a game.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |