Fifty years ago, the Profumo Affair erupted onto the British political landscape, leading to a Prime Minister’s resignation and to his government’s defeat at the ballot box. This chain of events was triggered at Cliveden House, a sumptuous stately home a few miles west of London. Cliveden remains filled with antiquities and surrounded by state-of-the-art landscaping, but its bedrooms are now open to us all, not just the aristocracy. Daralyn Danns charts its peaks and troughs.

It was one of history’s juiciest juxtapositions: The concurrence of the Cold War at its grimmest with the Swinging Sixties, a time for fun, frivolity, fashion and frolics.

Political intrigue and espionage had long gone hand in glove with romantic indiscretions as the favorite topics of contemporary newspaper columns. But the spotlight of infamy was now swiveling onto the British establishment. A senior cabinet minister had been caught up in a honey-trap involving a good-time girl and a Soviet naval attaché. Unraveling just over 50 years ago was a salacious affair that rocked the world and eventually brought down the country’s strait-laced government.

The epicenter of this “sex and politics” scandal was Cliveden (pronounced Cliv-den), an exquisite, quintessentially English country-house estate renowned at the time for extravagant parties that were attended by the social elite. The Profumo Affair, as the intrigue became known, propelled this rural idyll, some 20 miles west of London in the county of Berkshire, into the world’s headlines and blighted forever the Astor family, its long-standing occupants though no longer its owners.

It all started when William “Bill” Waldorf, the 3rd Viscount Astor and a member of one of the United States’ most eminent families, hosted a party along with his wife, Bronwen, at Cliveden in July 1961. The guests included the Secretary of State for War, John Profumo, and his wife, the celebrated actress Valerie Hobson.

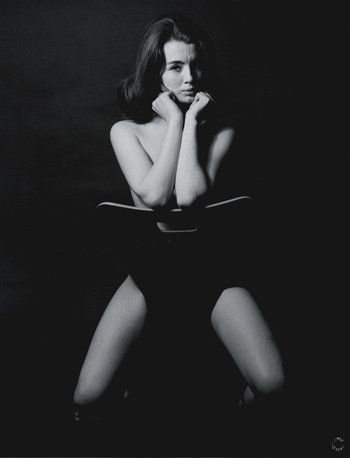

Swimming in the newly-installed pool that night, Keeler’s nubile form caught the eye of Profumo and triggered a catastrophic sequence of events. During the brief affair with the minister that followed, she was, allegedly, also sleeping with Ivanov.By a twist of fate, Stephen Ward, Cliveden’s resident osteopath who treated the rich and famous, was throwing his own party at Spring Cottage, elsewhere on the mansion’s estate. On his guest list were 19-year-old beauty Christine Keeler and Yevgeny Ivanov, a handsome Soviet naval attaché.

Pillow talk was viewed as a potential security risk and when details about Keeler’s sexual history were leaked to the press almost two years later, Profumo at first denied the relationship to the House of Commons. Admitting later that he had lied, he was forced to relinquish his post in disgrace. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan could not repair the damage done to his government and resigned himself shortly afterwards. The Conservative party, tarnished indelibly with sleaze, duly lost power at a general election a year later.

The Profumo Affair was hardly the only episode of historical significance to occur at Cliveden—and far from the only scandal. Indeed, the affair’s profile was made all the more tantalizing by the estate’s rich and colorful past. It has been the home of three dukes, an earl, three viscounts and Frederick, Prince of Wales, son of George II. Additionally, it has welcomed almost every British monarch since George I through its doors, including the present Queen—and has hosted almost as many infamies. In fact, you might say the estate was built just for that purpose.

George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, bought Cliveden in 1666. Renowned for his rakish, often scandalous behavior, he wanted to have a residence and hunting lodge close to London where he could lavishly entertain his friends and, in particular, his mistress, the Countess of Shrewsbury, whose husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury, he had mortally wounded in a duel two years later.

If the behavior of some Cliveden’s residents has been suspect since the start, at least the setting has been unassailable. Standing on chalk banks on the north side of the River Thames, the mansion is as elegant as it is bold, and the 376 acres of gardens and parklands are the stuff of country dreams.

The mansion proper has seen a few renovations over the years, twice due to fires, which have left the gardens and rear terrace as the only surviving parts of the actual first estate. The second fire occurred in 1849 shortly after the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland had moved in after adding Cliveden to the portfolio of other estates they owned. The house had to be completely rebuilt, and Sir Charles Barry (who also designed the Houses of Parliament) was commissioned for the task. The resulting three-storey Italianate villa stands today looking over the parterre, the jaw-dropping formal garden originally laid out in 1830 by Comte Alfred d’Orsay, which remains the jewel in Cliveden’s crown.

One of its biggest fans was Queen Victoria, an intimate friend of the Duchess who frequently traveled up the Thames from Windsor to take tea at the Spring Cottage—a haven of tranquility on the estate. As today’s guests can, she would have wandered around and enjoyed some of the numerous wonders from the Mediterranean that dot the grounds. Among others, there are the balustrade from the Villa Borghese in Rome, numerous sarcophagi and two ancient Egyptian granite statues of baboons that are approximately 2,000 years old. The ornate Fountain of Love, carved by Thomas Waldo Story out of marble and volcanic rock, is possibly the highlight and greets visitors as they arrive at the end of Cliveden’s long, tree-lined entrance drive.

Imagine Her Majesty’s displeasure in 1893 when she heard that all of these treasures and Cliveden itself had been sold to William Waldorf Astor, reputedly America’s richest citizen at the time.

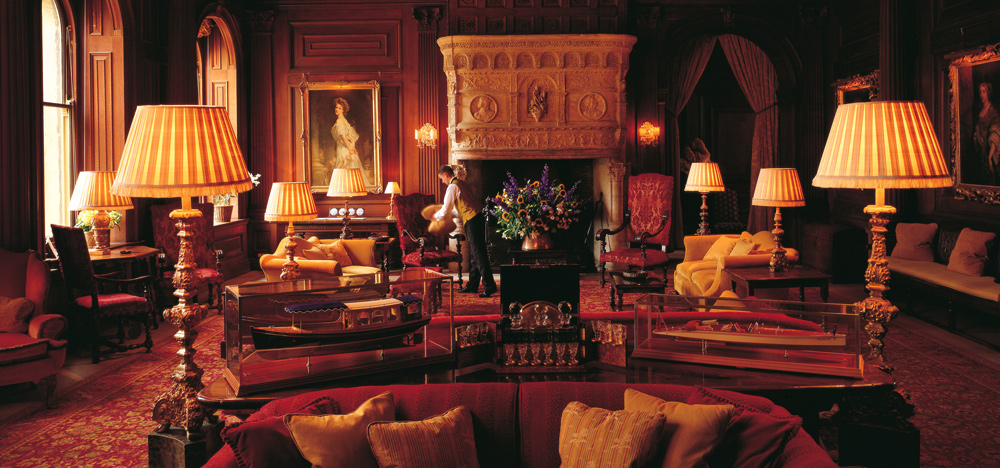

Astor, after serving as the U.S. ambassador to Italy, paid $1.25 million for Cliveden and made England his home, but the estate would hardly provide the rural bliss for which he’d hoped. Unhappiness came almost immediately with the death, aged 36, of his wife Marnie, Lady Astor. Following that, the grieving husband became a recluse and concentrated most of his efforts into putting his stamp on the house. Living under a portrait of Lady Astor (which still hangs on the wall, flanked by a great stone medieval fireplace), he revamped many of the rooms, enlarging the Great Hall and installing a rather grand wooden staircase.

Additionally, Astor bought the gilded paneling from Madame de Pompadour’s 18th century dining room at the Château d’Asnières, on the outskirts of Paris, and installed it in the French Dining Room, where it can be seen today. One of his more contemplative contributions to Cliveden is the garden maze, which he himself designed and which still provides guests the opportunity for recreation or meditation.

In 1906, the maze, the house and all of it was given by Astor to his son Waldorf as a wedding present, and the scene was set for yet more celebrity controversy. Waldorf’s wife, Nancy, was not only a legendary hostess but also the first woman to become an MP (Member of the House of Commons in the British Parliament). Her guests, as diverse as her own personal achievements, included Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Mahatma Gandhi, Charlie Chaplin and George Bernard Shaw. At that time, Cliveden’s weekend parties were the hottest ticket in town.

Lady Astor had an “open-door” policy, allowing all her visitors to air their views regardless of the company present. In the 1930s, the parties were rumored to have a distinct political agenda, and commentators accused the Cliveden set of holding pro-Nazi sympathies and trying to cajole British foreign policy towards appeasement. Clearly, long before the Profumo Affair, scandal, power and political intrigue were no strangers to this house.

Tabloid-worthy for a different reason, Cliveden played host to The Beatles when they filmed their movie Help!, and images from the lads’ time there are among the most charming and collectible of all the photographic records of John, Paul, George and Ringo.

Movie set, place of great joys and sorrows, hider of secrets and stage for infamies, at one point Cliveden even functioned as an overseas campus for Stanford University. Finally like many great former estates, Cliveden became a hotel in 1985. Upon hearing the news, former Prime Minister Macmillan supposedly remarked: “But it always has been.” (The former PM remained a regular Cliveden visitor well into old age despite the earlier difficulties the place had caused him.)

Today, half a century on from the Profumo Affair, the estate is owned by the British people under the auspices of the National Trust and operated on a long-term lease arrangement by the owners of Chewton Glen, a luxurious 5-star country house hotel and spa in the nearby county of Hampshire.

As Cliveden House Hotel, the estate continues its legacy of elegance, tradition and impeccable service—though with a bit more discretion these days. Not that it’s lacking in scandalous settings: There are 38 bedrooms and suites, all named for someone who made his or her mark at Cliveden.

Noticeably, none is named after Keeler, Profumo or Ward. But the swimming pool that brought down a government is still there and open to guests. No harm in taking an innocent little dip, is there?

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |