Fans love their champions, the seemingly immortal titans who stand atop their games like gods defying mortals on fields of battle. But those titans can fall, whether due to fate, vice, or just plain bad luck, and if there’s one thing sports fans love more than a champion, it’s a comeback. Tiger Woods is one such resurrected titan and his victory in the 2019 Masters has inspired a compilation of our favorite 10 sporting comebacks of all time.

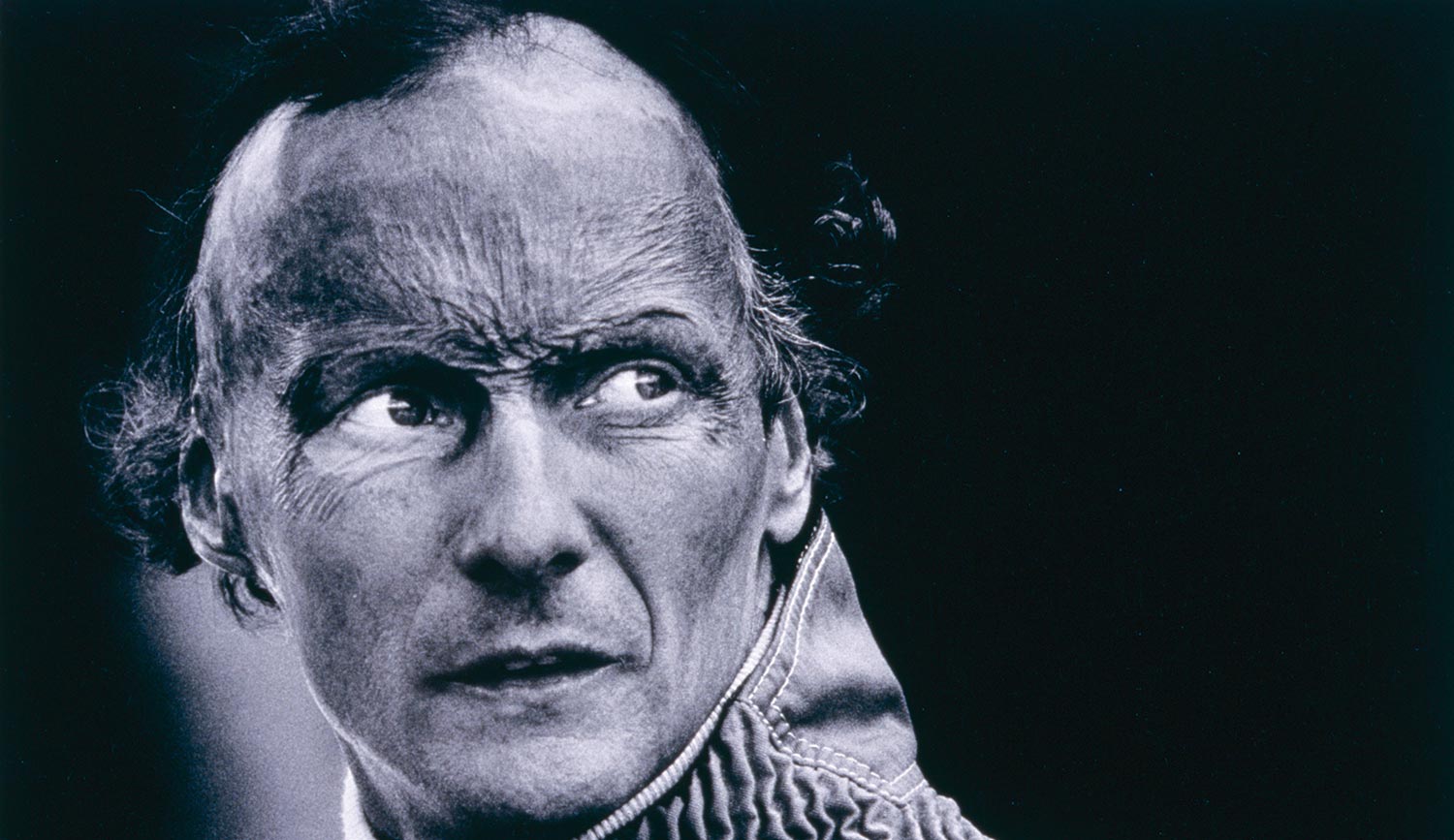

Racing Driver

Dis-owned by his aristocratic, industrialist grandfather for pursuing the folly of Formula One racing, Austrian Niki Lauda had accumulated debts of more than $200,000 by the time he finally secured a salary on the British BRM Formula One team in 1973.

Lauda possessed a potent combination of driving ability, intelligence and relentless determination, and having being lured to the Ferrari team he quickly reached the pinnacle of his sport in 1975 to become World Drivers’ Champion.

Lauda had won five of the first nine races of the 1976 season—on course to defend his Drivers’ title—when he arrived for the German Grand Prix at the mighty Nurburgring, boasting a 14-mile track notorious for its 174 corners. Lauda, 27 at the time, loved the unique challenge posed by the Nurburgring yet called on his fellow drivers to boycott the race because he knew the organizers could not provide sufficient ambulances, fire engines and safety staff for such a giant racetrack.

His protest lacked support and the race went ahead. With a terrible twist of irony, it was Lauda who suffered from a slow emergency response when his suspension failed and he drove his Ferrari into a bank. The car caught fire with Lauda unconscious in the cockpit. Other drivers became first responders, with Italian Arturo Merzario risking his own life by plunging into fierce flames to unbuckle Lauda and pull him from the wreckage. The burns suffered by Lauda were so severe that comatose in hospital that night, a priest read his last rights.

Lauda made it through the night and then had to endure agonising treatment for his burns and the reconstruction of his eyelids with skin grafted behind his ears. The fire had claimed half of one of Lauda’s ears, but he rejected the surgical rebuild because it would have delayed his return to racing.

Just six weeks after the crash the racing community was astonished when Lauda climbed back into the cockpit, his head bandaged, weeping and wedged back into a helmet. Ferrari had already hired a replacement driver and Lauda took this as an insult. He only missed two races and while he could not successfully defend his Driver’s title—the ambition for which had forced him out of hospital so soon—no-one could stop the irrepressible Lauda from re-claiming the title in 1977, completing the greatest driver rejuvenation in motor racing history.

Lauda won his third and final Driver’s title in 1984 before retiring from racing in 1985. His death, at the age of 70 in May this year, was mourned deeply by the Formula One community.

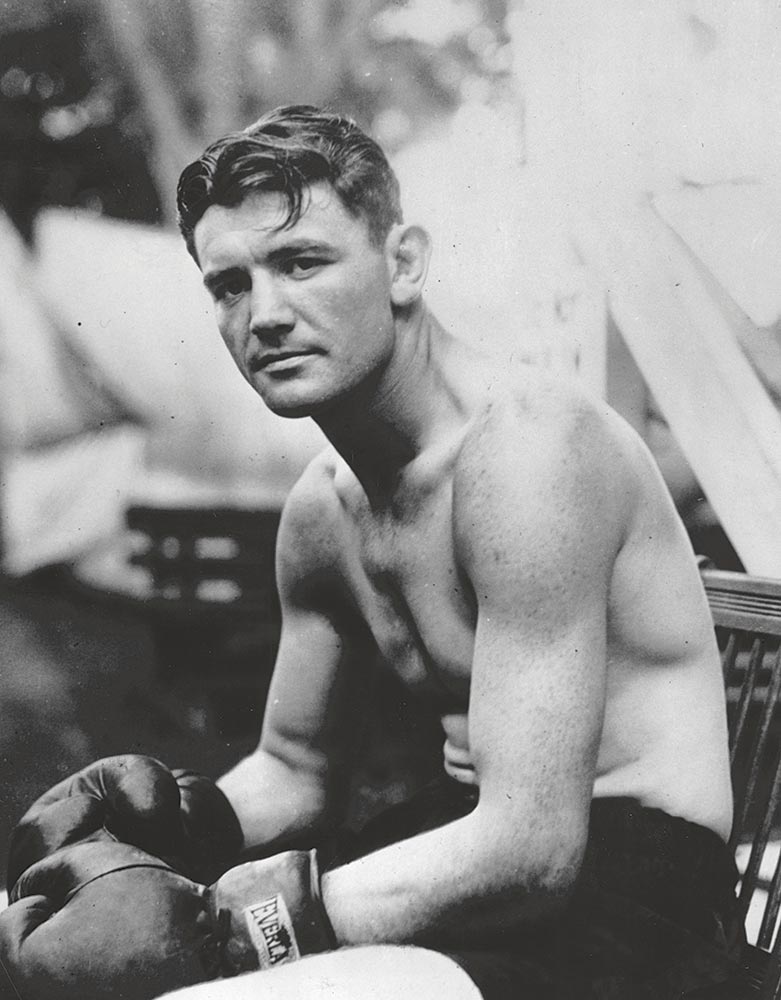

Boxer

On his way to the top of the boxing world in the 1920s, James “J” Braddock’s promising career was derailed by a tough loss for the heavyweight title in 1929. Along with the depression of losing what could have been a life-changing fight in a 15-round decision, Braddock nearly destroyed his right hand, fracturing it in several places during the bout.

Coming off a pre-title-fight record of 44–2–2 with 21 knockouts, Braddock stayed in boxing but, with his poorly-healed right hand a mess, he seemed all but done, losing 20 fights between 1928 and 1933.

The boxer was broke; his wife and three kids survived on bread and potatoes as the Great Depression slogged on and he turned to odd jobs and work on the New Jersey docks as a longshoreman to get by. His right hand weakened, the work compelled Braddock increasingly to rely on his left, unwittingly setting the stage for things to come. In 1934, he was offered money to fight John “Corn” Griffin, who was being promoted as boxing’s next big thing. Braddock was meant to be essentially a punching bag, another “W” on Griffin’s record, but—with a newly strengthened left in his arsenal—Braddock knocked Griffin out in the third round. A shocking victory over future light-heavyweight champ John Henry Lewis and a strong win over Art Lasky in 1935 set Braddock up for an unbelievable opportunity, a title shot against World Heavyweight Champion Max Baer. In fact, Braddock had been selected by Baer’s team as they felt it would be easy money for the champ. But on June 13, 1935, in front of a huge crowd at the Madison Square Garden Bowl, the boxer-turned-longshoreman entered the title fight as a 10-to-1 underdog and emerged victorious in a unanimous decision, wearing down the 26-year-old Baer and earning the title of “Cinderella Man” from one of the most dramatic nights in boxing history.

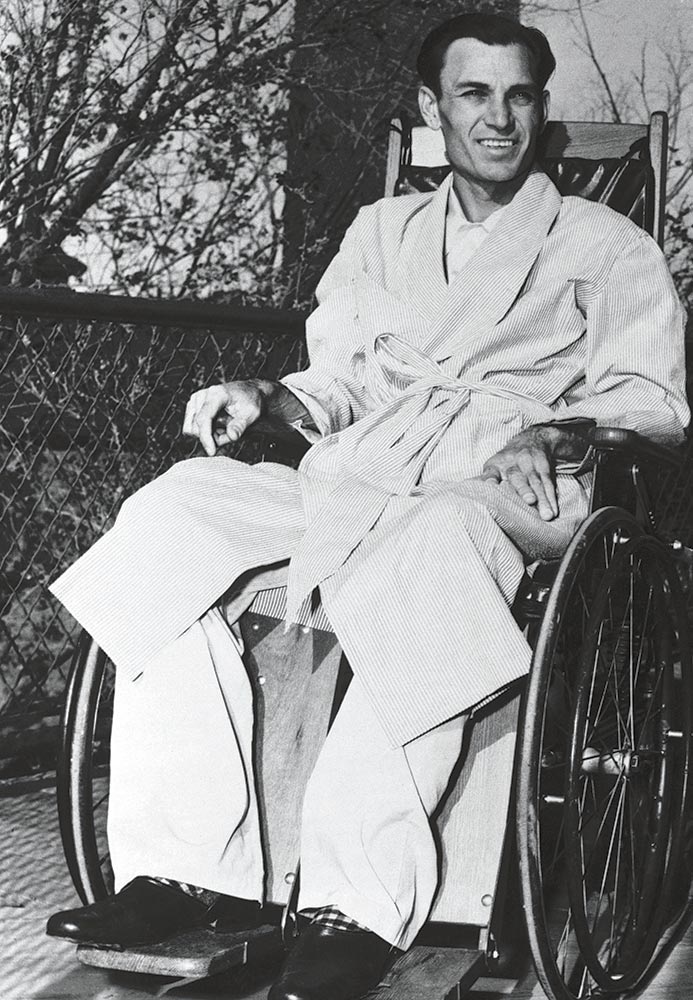

Golfer

On a foggy night near Van Horn, Texas, in February 1949, Ben Hogan and his wife Valerie were driving home from the Phoenix Open. Coming the other way a Greyhound bus driver, running behind schedule, attempted to overtake a truck but instead collided head-on with Hogan’s car. Hogan threw himself in front of his wife—a reaction that is thought to have saved both their lives—and suffered horrible injuries as the front of his car was crushed into his left side.

Hogan suffered a double fracture to his pelvis and fractures to his collarbone, left ankle and ribs. Then in hospital that night a blood clot brought the Grim Reaper bedside, before a surgeon from New Orleans was flown in by the US Air Force and saved Hogan’s life. That night the news wires first reported that Hogan had been killed.

Doctors speculated Hogan might not walk again, let alone play golf, but Hogan was the golfer who famously “dug [his game] out of the dirt”. He was the first golfer to return to the practice ground after a good round, his work ethic relentless. Arnold Palmer would later describe Hogan as “an icy monarch” ruling over the game.

Hogan had secured three career major titles by the time of the car crash and he somehow recovered to return to tour action a year later. Then at the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion—16 months after the crash and despite battling debilitating pain in his legs—Hogan won the title he would cherish most, but only after he had endured an 18-hole play-off to defeat Lloyd Mangrum and George Fazio.

They called it the “Miracle at Merion”.

Hogan would limit his playing schedule for the rest of his career, yet still win a further five majors, including a 1953 hat-trick of the Masters, U.S. Open and [British] Open.

Ben Hogan: Medical miracle

By Dr. Michael K. Ryan, Orthopaedic surgeon & sports medicine specialist, Andrews Sports Medicine & Orthopaedic Center

After six weeks in a hospital bed Hogan was assisted to a wheelchair and brought into the El Paso sun. In isolation, many pelvic fractures require three months before a patient can put weight on the legs. Compounding this was the ankle fracture and associated compromised circulation, which slowed recovery. Then multiple rib fractures and a collarbone fracture limit the ability to support oneself with a walker, further inhibiting Hogan’s recovery.

Assuming Hogan was able to stand at the earliest in June 1949, he then took only 12 months to learn to walk, build upper and lower body strength and regain flexibility and mobility to play golf. To swing a golf club effectively, the entire body must work in concert to simultaneously provide lower body stability, in order to allow the upper body to rotate, loading the back leg to generate enough torque through the hips, ultimately pulling the upper body and torso through the ball to contact and follow through. Any stiffness, weakness or deficiency in the ankles, knees, hips, pelvis, spine, shoulders, elbows, or wrists would inhibit the swing.

Hogan’s swing at the 1950 U.S. Open demonstrates none of this, only 14 months after the crash. Perhaps it was good medicine, but more likely it was Hogan’s resolve. Medicine and surgery can treat the body and the body can heal, but recovery demands struggle, pain and persistence. Remarkable about Hogan’s recovery was that he regained such precise, fluid function in such a short amount of time.

Golfer

By November 2017 the World Ranking of Tiger Woods had slipped to 1,199th. Statistically it was the lowest ebb for a golfer whose record of 683 weeks at number one may never be broken. Many consider Woods to be the greatest golfer of all time but it appeared physically impossible for him to rekindle any semblance of golfing competitiveness. Yet in April this year he became a major champion once again, winning the Masters for the fifth time—the 15th major title of his career.

When Woods won his first major—the 1997 Masters—he became the first black golfer to win at Augusta National, the youngest ever winner of the Masters and he set 20 scoring records on his way to winning by 12 shots. Over a single weekend in Georgia, Woods triggered a boom in global golf that would last a decade.

Woods won his 14th major at the 2008 U.S. Open, playing against doctor’s orders and with what would turn out to be a broken left leg. His leg injuries were just the beginning of Woods’ decline though, as the following year his marriage collapsed as details of his lurid private life emerged. The kiss-and-tell candidates made an orderly line.

Woods recovered a sense of equilibrium in his personal life but his body was in tatters. A series of knee procedures and four back operations took their toll. Woods stubbornly refused to surrender but his dogged pursuit of more silverware looked futile. Impossible. The game had moved on. Not only was Woods no longer one of the longest drivers but the new breed—Rory McIlroy, Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka—were hitting the ball much straighter than Woods too.

At the 2017 Masters, Woods had to take a “nerve block” injection so he could just walk to the Champions’ Dinner and sit at the table.

Some world-class form finally began to return for Woods in the Spring of 2018. He challenged down the stretch at both The Open and PGA Championship, defeated McIlroy in the season-closing Tour Championship and brought an outside chance to the 2019 Masters.

It was not the spectacularly dominant Woods at Augusta this year but he patiently constructed his challenge. Then when nervous mistakes took their toll on his final-round rivals—Francesco Molinari, Koepka and Xander Schauffele included—Woods held firm to win by one. “Tiger, Tiger,” chanted an elated crowd around the 18th green.

It was 11 years between Woods’ first and 14th major victories, and another 11 years between his 14th and 15th.

“It’s overwhelming just because of what’s transpired,” said Woods. “Last year I was just very lucky to be playing again… This was one of the hardest I’ve ever had to win.”

Cyclist

Crashed in a race, then shot with a shotgun, the miracle was not that Greg LeMond won the 1989 Tour de France, it’s that he was on a bike at all. Two years earlier, fresh off his 1986 Tour win—the first by an American—the then-25-year-old broke his hand while racing in Italy. He returned home to California to recover for a couple of months but, just before returning to Europe to defend his Tour title, everything changed. While hunting with his uncle and friends, a confused hunter mistook the cyclist for game and shot LeMond with a 12-gauge shotgun. It was an hour before a helicopter arrived, another half hour or so until he was in surgery. There were more than 100 shotgun pellets in his body; two of LeMond’s ribs had been broken, his left ring finger was shattered; he’d lost nearly three pints of blood, and much more had pooled in and around his lungs, causing them to collapse. The membrane around his heart was leaking blood as it, too, had been perforated by pellets. Holes in LeMond’s diaphragm and small intestine were repaired in surgery, holes in his liver were left alone. And while a number of pellets were removed, five remained in his heart, five in his liver, and two dozen more in his back, arms and legs. In the end, LeMond lost nearly half the blood in his body, his small intestine leached waste and his one good kidney was damaged (his other had failed in childhood). Doctors credited his strong heart and lungs with getting him through, but his body was devastated and wracked with pain. Over the next few months, barely able to shuffle across a room, LeMond lost 30 of his 150 pounds, his leg muscles withered and his body fat jumped from 5% to 19%. Further health complications followed over the next year, some severe, but eventually LeMond climbed back on his bike and, just two years after being shot, won the Tour de France for the second time. A third victory followed in 1990 and then he retired. As Tour victories by Lance Armstrong and Floyd Landis were disqualified due to doping, LeMond remains the only American to have won cycling’s greatest race.

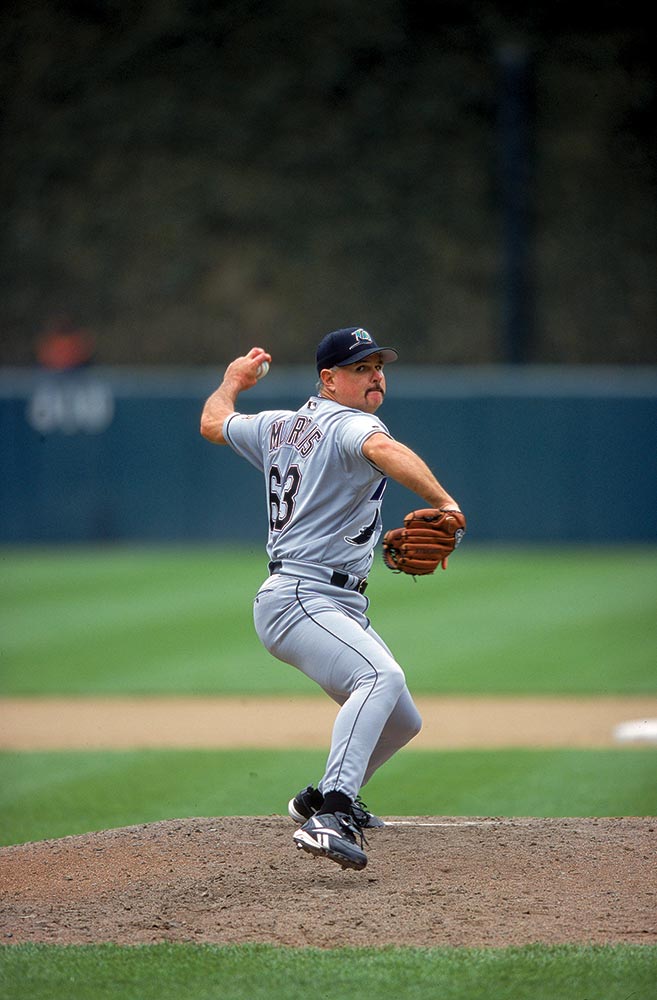

Baseball player

A once-in-a-generation-talent and the first pick of the 1999 MLB draft, Josh Hamilton had a $3.96 million signing bonus with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays and a God-given ticket to stardom. In high school he’d run the 60-yard dash in 6.7 seconds and had a 97mph fastball that blew batters off their feet. But in 2001 Hamilton was in a car wreck. Four years later he was unrecognizable, a junkie turning up on his grandmother’s porch at 2am. Injuries from the wreck had sidelined him and his frustration led to drinking, bad behavior and so it went. As Hamilton told USA Today in 2006, he once deliberately burned his “magic” left hand with four lit cigarettes while in a rage. He blew his money trying “literally every drug on the street,” including smoking crack. He said, “I did it so much it was like smoking cigarettes.” The 6’ 4” 235-pounder dropped more than 40 pounds, and so when he was given permission by MLB to take a second shot in 2006, there was a lot to do. He put several suicide attempts and his shame behind him, reconnected with his wife and daughters after having been kicked out and, as the paper put it, “was scared straight.” Hamilton worked at a baseball facility in Clearwater, Florida, rising early each day to pull weeds, mow the outfield, clean toilets and take out the trash while he rediscovered his game in his spare time. It worked, and in 2007 Hamilton rejoined the big leagues. He was named to the 2008 AL All-Star team playing for the Texas Rangers and made the All Star team the next four seasons as well.

The 2010 AL MVP, Hamilton’s career took on some of the shine of his original promise, including a distinguishing moment in 2012 when he became just the 16th player in MLB history to hit four home runs in one game. This August he was inducted into the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame, and as Hamilton himself wrote in ThePlayersTribune, “my immediate reaction was pure gratitude—just a massive amount of gratitude and appreciation.”

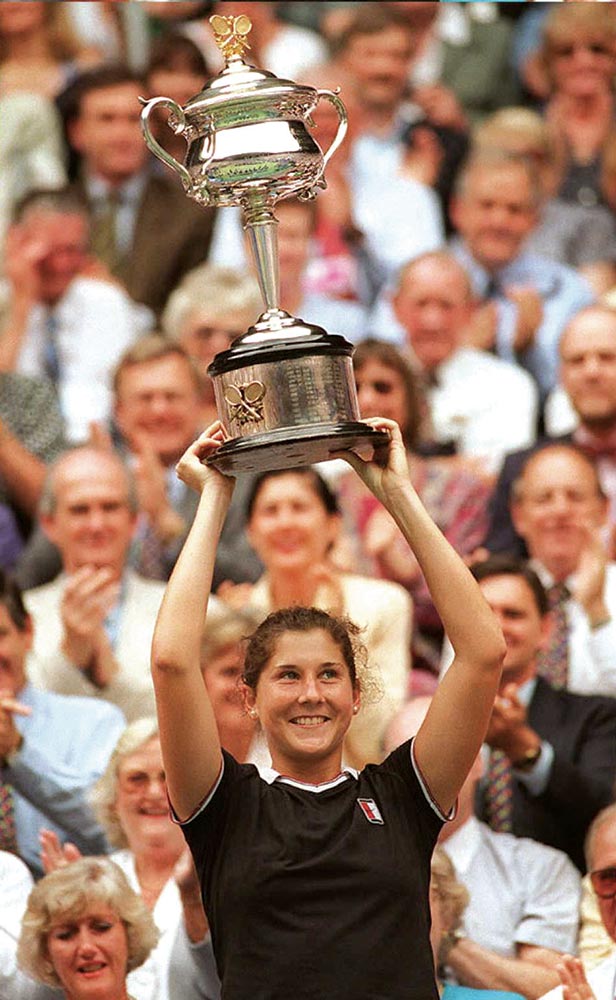

Tennis player

Women’s tennis is a conveyor belt of teen stars, but none more prolific than Monica Seles. In 1990, aged 16, the Serbian-American became the youngest ever French Open champion when she defeated Steffi Graf in straight sets. By the time she turned 20 Seles had accumulated eight grand slam titles and had succeeded Graf as world number one.

Seles’ irrepressible rise was more than fan Gunther Parche could bear. In Hamburg on April 30, 1993, Parche—who was obsessed with Graf and a German supremacist with learning disabilities—stabbed Seles in the back with a kitchen knife while she sat courtside between games.

The blade fortunately only penetrated by less than an inch and Seles recovered from the wound physically within weeks, but took a two-year break sabbatical. After less than six months in pre-trial detention, Parche was sentenced to two years’ probation and psychological treatment, prompting Seles to vow never to play in Germany again.

Seles returned to competitive action at the 1995 Canadian Open and won, setting a record by dropping only 14 games. Seles then reached the U.S. Open final where she lost to Graf, but at the 1996 Australian Open there was no stopping her. Seles defeated Anke Huber in the final to claim her fourth Australian Open title and ninth grand slam title.

Seles would reach more grand slam finals but could not resurrect her former consistency. Even with nine grand slams, the question remains: what could have been for Monica Seles?

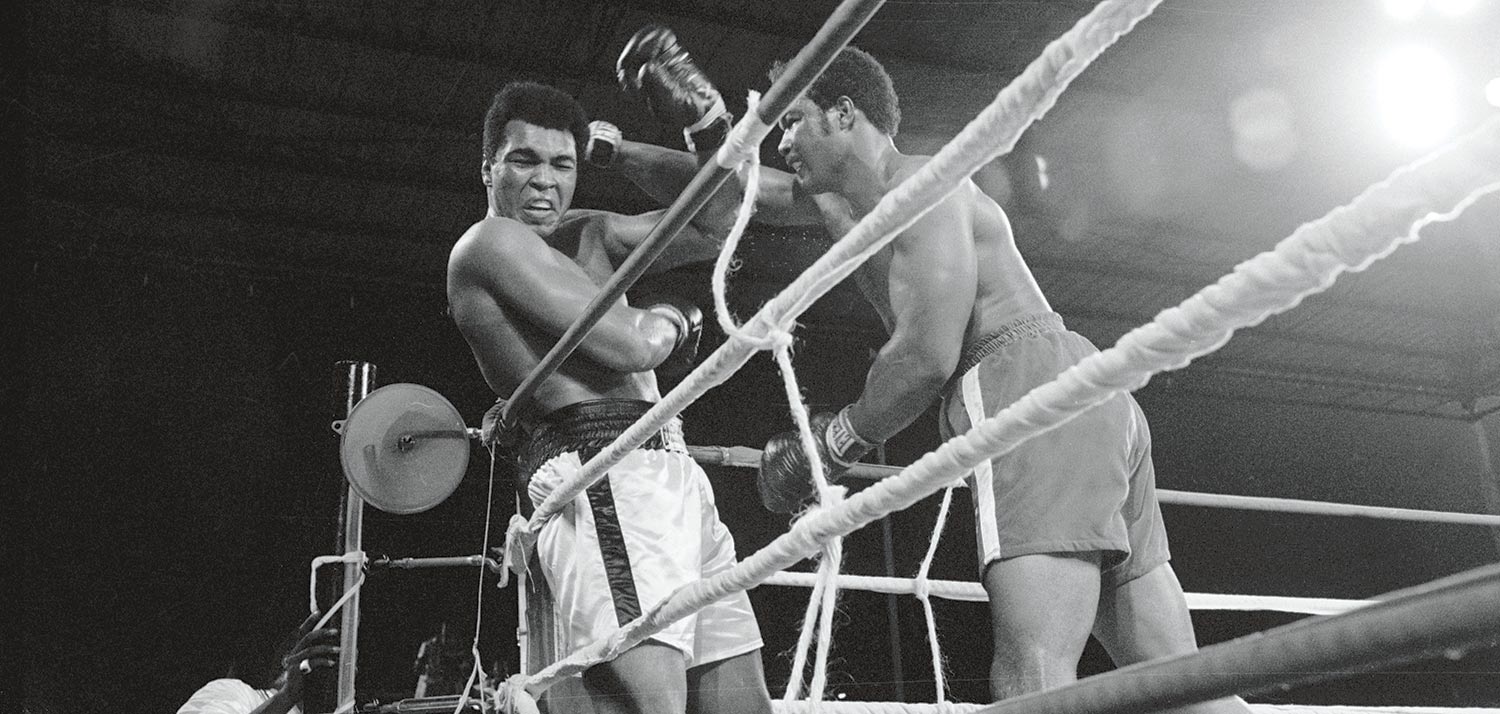

Boxer

In 1967, Muhammad Ali, 25 at the time and the heavyweight boxing champion of the world, became the most famous man to refuse to fight in Vietnam. “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” he declared. In the midst of an historic civil rights movement in the United States, Ali said that “no Vietcong ever called me a nigger”.

“Just take me to jail,” he said, and they could have done but Ali was granted bail. Overnight he became a national pariah, Ali’s boxing license was suspended and his world title stripped. He lost three years of his career at the height of his prime.

Ali’s conviction was overturned in 1971 but he returned to the ring short of his old spring and swagger. After two tune-up bouts he faced Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden in New York for the world title. Frazier knocked Ali to the canvas in the 15th round and won by unanimous decision. It was Ali’s first professional defeat and prompted widespread claims he was washed up.

Ali would defeat Frazier in a re-match in 1974 but by then Frazier had lost his world title to giant George Foreman, a fighter of peerless power. In the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire [now the Democratic Republic of the Congo], on October 30, 1974, 32-year-old Ali was the underdog and 25-year-old Foreman—who had knocked out Frazier in 1973—was 40-0 and at his brooding, menacing best.

“If you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait ‘til I whup Foreman’s behind,” claimed the ever-confident Ali. “I’m so mean I make medicine sick,” he declared.

With an estimated worldwide television audience of one billion—the world’s most watched live broadcast at the time—Ali invited Foreman to swing freely with a “rope-a-dope” tactic in the middle rounds that defied convention. Ali taunted Foreman, dodged punches and absorbed a pounding. Then in the middle rounds Ali switched gears, once Foreman was exhausted, and sensationally Ali knocked him out in the eighth. Ali was world champion again, eight years after he had first won the crown.

Baseball player

A Navy kid born in Texas, Jim Morris wasn’t an obvious candidate for greatness, drafted 466th overall by the New York Yankees in the 1982 draft. He declined, and the following year was drafted fourth by the Milwaukee Brewers, with whom he signed, although Morris then suffered several arm injuries in the minors. A series of surgeries didn’t help, including one that involved replacing a tendon in his left elbow with one from his right ankle, and in 1987 the pain became too much and he was released, never having made it to “the big show.” One year with the White Sox didn’t go any better, and so in 1988 Morris became a high school physical science teacher. Morris, his wife and three children moved to Big Lake, Texas, and he retired from baseball with a minor league record of 17 wins and 22 losses. For the next 10 years Morris taught and coached the school’s baseball team, the Reagan County Owls. Trying to motivate his team in 1999, he promised that he’d try out for a Major League team if they won their district championship—which they’d never done. As it happens, his team took the title and Morris kept up his end of the bargain, attending an open tryout for the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. Incredibly, despite his age (35), injuries and a decade away from the game, he threw 12 consecutive 98mph fastballs and was given another chance. After a few games in the minors, on September 18, 1999, Morris realized his dream and took the mound in the majors, pitching against Royce Clayton of the Texas Rangers, whom he struck out on four pitches. Morris made 16 major league appearances in 2000 before his arm injuries returned and he was released. Disney made a film about Morris called The Rookie, in which the pitcher was played by Dennis Quaid.

Football quarterback

In the first pass play of the first round of the 2006 AFC Playoffs, playing in his third NFL season, Cincinnati Bengals quarterback Carson Palmer stepped back and delivered the longest completed pass in Bengals Playoff history: a 66-yard bomb to rookie receiver Chris Henry. Normally the former USC standout would have jumped up in celebration, but after he’d released the ball Pittsburgh Steelers defensive tackle Kimo von Oelhoffen had brought Palmer down hard, wrapping up his leg while on the ground, a move for which the Steeler later apologized. The injury nearly took Palmer out of football: it tore his ACL and MCL, dislocated his patella and effectively destroyed his knee. Rather than retire so early into his career Palmer elected to have a dramatic series of surgeries. Using an Achilles tendon from a woman who’d been killed several years before and employing other creative solutions, surgeons reconstructed Palmer’s knee, though the head doctor had called the injury “devastation and potentially career-ending.” Unbelievably, Palmer pushed through rehab and returned the following year as the Bengals starting quarterback, starting all 16 regular season games en route to one of his best seasons ever. At the time of his retirement in 2018, he was 12th all-time in both passing yards and passing touchdowns.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |