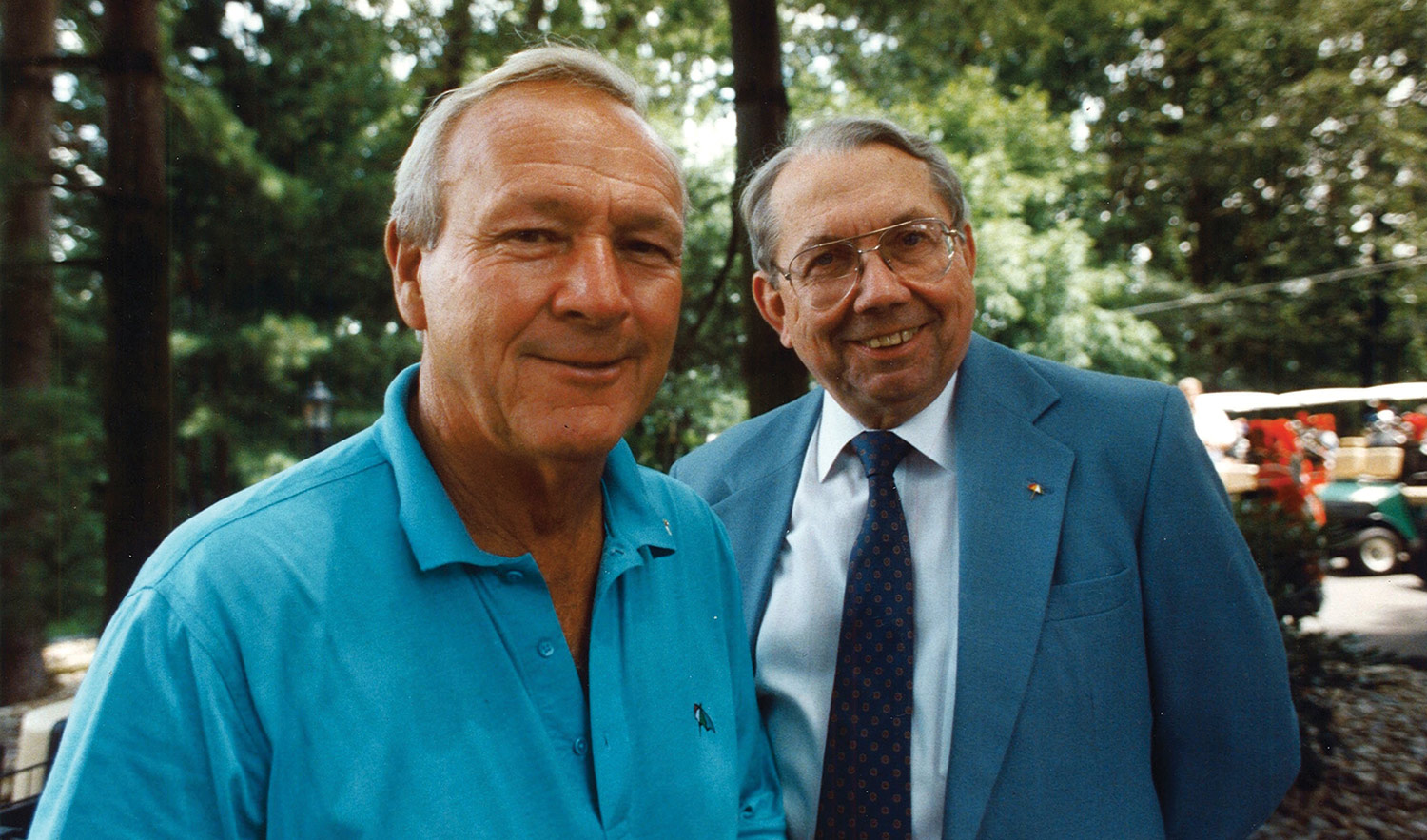

Arnold Palmer: Hero of Western PA. Doc Giffin accepted the role as Assistant to Arnold Palmer in 1966. It was a job he fulfilled for more than 50 years, for the rest of Palmer’s life. Resident in Latrobe, Pa., Giffin here charts Palmer’s lifelong attachment to many of the golf courses of Western Pennsylvania

The golfing world knew very little about Arnold Palmer in the late 1940s and early 1950s, but he was no secret to the aficionados of the game in Western Pennsylvania, especially those at the country clubs in the southwestern corner of the Keystone State. The area is flush with fine clubs and courses and many of them—like the old proud claim of innkeepers that “George Washington slept here”—can and do boast that “Arnold Palmer won here.”

Then in his late teens and early 20s, young Palmer was tearing up the competition nearly everywhere he went in this golf-rich area. From the age of 18 he won the prestigious West Penn Amateur five times on excellent courses—Oakmont, Fox Chapel, Longue Vue, Shannopin and Alcoma—to go with victories in the West Penn Junior at Highland and South Hills (and he later won the West Penn Open at Fox Chapel).

Neighboring Greensburg Country Club staged an influential invitational and he won that three times over a four-year span in the early ’50s. He topped the field at Sunnehanna Country Club aged 19, just before that tournament in Johnstown officially became the Sunnehanna Invitational, which is now among the country’s top amateur events.

The focal point, though, was Latrobe Country Club, an unpretentious private club on the edge of Latrobe—a small industrial town some 40 miles southeast of Pittsburgh—and its tight little nine-hole course. That’s where Milfred (Deke) Palmer spent most of his life, beginning as a teenage member of the crew that built the course in 1920-21. That led to a job on the club’s original grounds force for Deke and a few years later he was appointed superintendent. A man of real endeavor, integrity and talent, in 1931 he became the golf professional as well.

It’s at Latrobe where his first born, Arnold, grew up and learned to play the game.

That’s where Arnold first made a name for himself with his prowess as the best player in the region’s high school circles from his freshman year on.

That’s where, in 1971, because Latrobe Country Club meant so much to him and his family, Arnold purchased the club, despite the objection of his father. The executives of Latrobe Steel Company, who were the controlling and operating stockholders among the club’s member owners, offered the club to him. The company found it necessary to divest itself of the property because of the hard times the speciality steel industry was experiencing.

By then 18 holes, designed primarily by the Palmers, the club had become a bit rundown and outmoded, and badly in need of serious refurbishing. That was the main reason Deke Palmer thought his son’s impending purchase was a bad idea and told him so. Despite this, Arnold went ahead with it, willingly plunging sizeable amounts of his money into major improvements that brought it up to the modern standards of the time. Besides, it gave him the playful opportunity to remind his father that Arnold had become his boss.

As you might imagine, Arnold found that one funnier than Deke.

Meaningful as Latrobe Country Club was to his life, several other clubs and courses in Western Pennsylvania played significant roles in Arnold’s golfing career.

For one, Laurel Valley Golf Club, just 10 miles east in Ligonier.

Palmer was deeply involved in Laurel Valley from its founding in 1959. In fact, that association might have short-circuited his astounding career if he had accepted the club’s offer, prior to its opening, that he become its home professional. Instead, Arnold became its touring professional. He was paid a modest monthly fee right up to the time of his passing last year and supervised a number of design changes to the course over the years through his Arnold Palmer Design Company. His contributions to the club were recognized when the club erected a statue in front of the clubhouse in 2009 to mark Arnold’s 80th birthday. He was certainly honored and thrilled about that.

Arnold was instrumental in putting Laurel Valley high on the international golfing map. First and foremost, he influenced the PGA of America—searching for a replacement course with no time to spare—to award its 1965 championship to the club. That was quite a week for him. Arnold even had a big tree transplanted overnight, on the eve of the tournament, beside one of the tees to block out a hazardous shortcut players had discovered during their practice rounds.

Playing the PGA Championship on a course that he knew so well, Palmer had an excellent chance to win the only one of the game’s majors not already on his record. President Dwight Eisenhower, by then a good friend, gave him a little encouragement by betting $10 that he would win. Sadly it didn’t happen, thanks primarily to two penalty situations, one rules violation occurring when a marshal ironically named Miles Span, and several of his associates, tore a railing off a temporary bridge to give Palmer a clear shot to the green on his very first hole of the tournament.

Shortly thereafter, Arnold received a commiserating note from the President along with a $10 bill. Perhaps that was the only bet Arnold ever made that he wanted to lose. He never did win the PGA Championship.

Following that otherwise-successful week, Laurel Valley hosted the Tour’s National Team Championship in 1970, 1971 and 1972, with the powerhouse pairing of Palmer and Jack Nicklaus winning the first two. (Nursing a hand injury, Nicklaus did not play in 1972.) Three years later, the Ryder Cup came to Laurel Valley with Palmer, not playing, captaining the U.S. team to a decisive victory. Later on, the club hosted the U.S. Senior Open (1989), the Senior PGA Championship (2005) and the Marconi Pennsylvania Classic (2001).

Oakmont was another area club of particular significance for Palmer, evoking a combination of admiration and bitter disappointment.

He came out on the short end of one of the game’s greatest U.S. Opens there when he lost in a playoff as Nicklaus won the first professional victory of his marvellous career, in 1962. Arnold saw another possible Open title escape 11 years later when Johnny Miller scorched Oakmont with a closing, record 63—a truly remarkable round of golf.

But those disappointments did nothing to dim Arnold’s fondness for Oakmont, its members and professionals, Lew Worsham and Bob Ford, that began when he got his first chance to play the course when he was in his early teens. A few years later, he was excited and then quickly dismayed when his father was offered the job of pro-superintendent at Oakmont and turned it down, deciding he and his family were content and happy with their life at Latrobe Country Club.

Two other Western Pennsylvania courses are landmarks in the career of Arnold Palmer. In the late 1960s, well before he got into the business formally, he designed his first course at Indian Lake, a resort community in the Allegheny Mountains, not far to the east of Latrobe and near where ill-fated Flight 93 came down on 9/11 in 2001. Indian Lake had two unique features—a tree in the middle of one fairway and a tunnel leading from one green to the next tee under an airport runway.

Many years later, Arnold’s company—which has produced or remodelled and updated some 300 courses around the world during its existence—designed its first and only major course complex in the Western Pennsylvania area; 27 holes interlacing a residential community built around the impressive Treesdale Golf and Country Club in the northern suburbs of Pittsburgh, on land that had been for many years an apple orchard.

While Arnold would spend his winters at Bay Hill in Florida, and in Palm Springs, California—places he loved dearly—his heart and his primary home always remained in Latrobe. He never lost sight of that, which is one of the reasons why Arnold Palmer made such an indelible mark on the history of golf in Western P.A.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |