One of the most charismatic and controversial figures in NFL history, Jim McMahon has fluid drained from his brain four times per year. He speaks eloquently about coping with his football injuries, he rails against the effects of pharmaceutical painkillers and the system that supplied them, and during nearly half of the year, he plays golf — which is how Paul Trow met him. Paul kept his shoes on. Jim did not. Here’s why…

Bermuda is a beautiful, expensive and conservative island; some might even call it “twee” due to its spotless pink beaches, eponymous shorts, fastidious financial discretion and 20mph speed limit. Yet it was in this unlikely setting—a monument to politeness and colonial gentility—that I became acquainted with a true force of nature. Step forward, always barefoot when golfing, Jim McMahon.

With monikers like “Mad Mac” and “McManiac” stalking him still as he strides unconventionally yet purposefully through the second half of his life, the 58-year-old former quarterback—a proud possessor of two Super Bowl rings—is still picking out his targets with pinpoint accuracy. During our sojourn to Bermuda for an unimportant yet fiercely contested golf match between American and British media folk, I asked him whether he’d do anything different if he had his career to do over.

“Paul,” he barked, “you’re just like those fans who gave me a hard time in Philadelphia [the third of his seven teams]. Even when we were 30 points up they used to holler at me.”

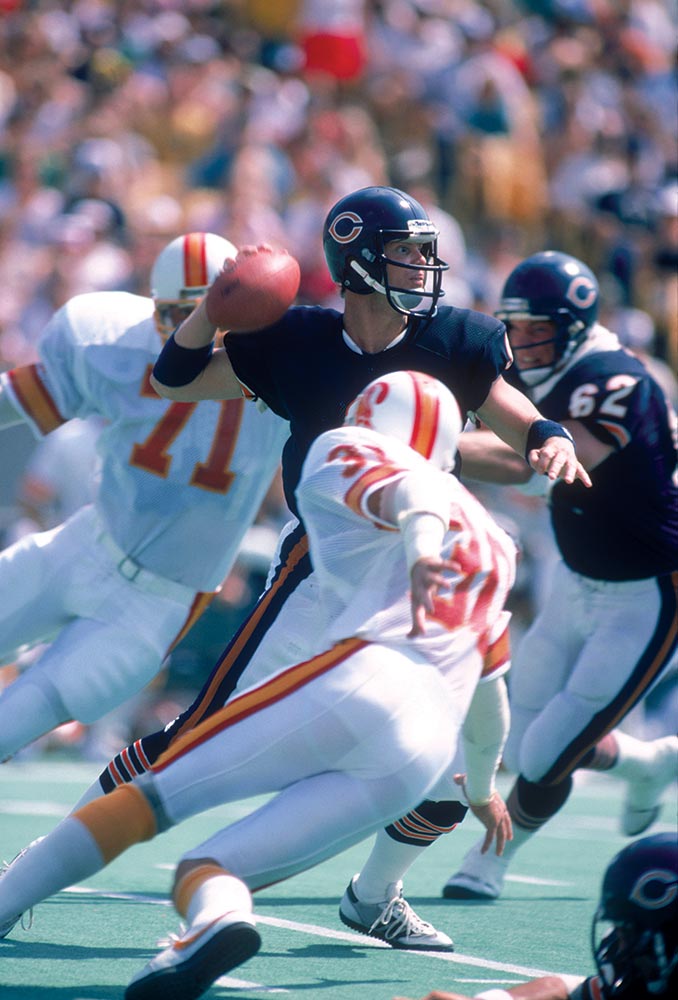

Back in the 1980s, McMahon was a brash playmaker who scaled the game’s pinnacle with the Chicago Bears despite clashing frequently over tactics and discipline with coach Mike Ditka, a man renowned for his short fuse.

The press and public loved McMahon for his outspoken views and outlandish behavior and it’s no wonder that he starred as the “punky QB” in the Bears’ 1985 rap video, The Super Bowl Shuffle, filmed to raise funds for a Chicago charity. He once mooned sports writers when they asked about an injury to his buttocks, and he made his first public appearance for the Bears holding a can of beer. Despite all of this, however, he was the real deal, the best rollout passer of his era and incredibly adaptable to changes on the field. In 1985 his sharpened talents were complemented by an amazing cast of teammates that included the wondrous running back, the late Walter Payton—aka “Sweetness”—the gargantuan defensive lineman William “Refrigerator” Perry, and legendary linebacker Mike Singletary. Together they achieved sporting immortality with a 46-10 demolition of the New England Patriots in Super Bowl XX. They were legends, regarded by many as the greatest NFL team in history, a claim that would be indisputed were it not for the undefeated 1972 Dolphins (and it’s still a toss-up).

Six teams and 10 years later McMahon signed on for the 1995-96 season with Chicago’s fiercest rivals, the Green Bay Packers, as a backup QB to Brett Favre. He threw only five passes as a Packer, and the Green Bay fans (along with much of the football world) never really could accept him in the green-and-gold uniform that he’d so happily walked all over as a Bear. McMahon was still on the team when the Packers won Super Bowl XXXI, and though they released him after the victory he was invited to accompany the team to the White House to meet the President. He accepted, but—in true McMahon fashion—he showed up in a Bear’s jersey.

That is the McMahon people love to recall, the brash, strong, do-as-I-please leader. But his career as a warrior came with a price, which he’s now paying. After numerous concussions, a broken neck and a lacerated kidney, the retired football star has more recently been diagnosed with early onset dementia.

“All my joints hurt but the headaches are the worst,” he says. “My head used to hurt so bad I would mostly stay in my room for months at a time with the shades down. Any kind of light hurt. Often, I couldn’t remember where I was or what I was supposed to do. The pain was like somebody sticking ice picks in my head.”

His struggles with headaches, dizziness, depression and memory were revealed in a 2012 Sports Illustrated article that drew attention to the long-term health consequences of playing football and prompted a phone call from New York chiropractor Scott Rosa offering his help.

McMahon flew to New York and, after a week of analysis, Dr. Rosa told him his neck was out of alignment and had caused a blockage that trapped fluid on his brain. The solution was to manipulate his neck vertebrae on the treatment table to open the blockage.

“It’s called ‘image guided atlas treatment,’” McMahon explains. “The first time he did it, my head was so full of stuff it literally felt like a toilet being flushed. I could actually feel the stuff draining out of my head. There’s no cure for this condition so I go back to New York every three months because the fluid keeps building up in my brain.

“During the three months before my next check-up I get increasingly bad headaches. It’s hell getting on a plane with your head all swelled up. I literally squeeze my head for four or five hours on a flight. But as soon as he adjusts me, I’m good again.”

With the NFL becoming increasingly concerned about long-term head injuries, McMahon urged Commissioner Roger Goodell to speak with Rosa. But he says Goodell rebuffed him, saying he trusted the Harvard neurosurgeons the league had hired to study the issue. Another bone of contention with NFL officialdom concerns marijuana.

“In-between my visits to New York, the only way I can ease the pain is to smoke a joint,” he says. “Here in Arizona it’s legal medically, to relieve inflammation. I use Cannabidiol—a marijuana derivative known as CBD—which would work for a large percentage of the population with chronic injuries and doesn’t make you feel stoned.

“When I was playing, the team doctors would hand out painkillers—Vicodin, Percocet or Oxycontin—like candy, and keep shooting you up to deaden joint pain. But according to the NFL you can’t smoke a joint because that’s bad and addictive. That’s ridiculous. Marijuana is a medicinal herb, not a drug, it’s not addictive and it’s not a chemical. It’s been demonized because it’s got natural healing properties. I was in pain my whole career and some weeks I’d be forced to take more than 100 pills.”

This is McMahon in full flow. A man on a mission.

“You can’t stop the head trauma—it’s part of the game—but we’re trying to make sure that guys are checked regularly,” he says.

He delivers an especially tough message when speaking to parents about youth football, telling them to keep their kids off the gridiron until they are juniors in high school.

“They can learn the fundamentals playing flag football,” he says. “When they’re in high school, their bodies are physically able to hold up. A lot of parents and kids don’t want to hear it. But I ask parents, ‘would you rather see your son play football or be in a wheelchair?’”

To back up his commitment to providing effective treatment for traumatic injuries—those suffered by war veterans as well as footballers—he is setting up an alternative dispensary business with some investors in Los Angeles. He also plans to donate his brain for research. “I’m not going to need it after I’m dead,” he says.

Born in New Jersey and raised in San Jose and Utah, McMahon first came to prominence as a standout at Brigham Young, though he explains his family was Catholic, not Mormon.

“My father was an accountant who worked for a paper company that moved him around during his working life. My parents, who will soon be celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary, have lived near Las Vegas for the last 22 years.”

McMahon completed his communications degree at Brigham Young in 2014—37 years after beginning it—and 18 years after quitting as a player.

“I promised my elder daughter I’d stop when she got to high school. I’d uprooted my kids all through their early childhood with my various moves to different teams and the time had come, when I was 37, to call it a day. ”

Father to four (two boys and two girls) and now a grandfather to two (“one of each”) McMahon has lived in Scottsdale, Arizona since 2010: “I’m not a member of a golf club as such. I play mostly at Grayhawk and Troon North when I’m here as they’re only five minutes from where I live. My handicap has drifted out to eight. But I travel almost 200 days a year and most of that is for golf—charity events and fund-raisers for veterans, mainly.”

When we talked after meeting in Bermuda, McMahon had just returned from an event in Florida organized by Robert Gamez (who won the 1990 Arnold Palmer Invitational at Bay Hill), and I wondered: why golf in bare feet?

“I had my feet stepped on so many times by linemen that the restrictions I suffer wearing golf shoes now bring back those pains,” he explains. “It’s not a rule of golf that you have to wear shoes to play. In any case it helps me keep my tempo. It’s fine when I’m playing on grass or out of sand traps, but a little more awkward if I have to go into the cactus and rocks we get here in Arizona. That gives me an incentive to keep it straight!

“Mr. Palmer, who I met a few times, once asked me why I did it and upon hearing the reason he commented that Sam Snead used to do it, ‘and it never did him any harm.’”

For his next act, the intense player-turned-medical crusader is doing a show in Vegas at Cesar’s Palace, appearing with former running back Ricky Williams and baseball’s Jose Canseco to chat sports and answer audience questions.

He’s in the College Football Hall of Fame but conspicuously absent from the pro hall: “That’s all about statistics, and you don’t have good stats when you play for Ditka,” he explains. “He didn’t like me changing the plays and always thought I did it to piss him off. But I did it to win games. He wasn’t a very good offensive coordinator. He didn’t know what the hell he was doing.”

It’s not too late for McMahon to be inducted in recognition of his playing exploits, and it could happen anyway if he helps to make the game less dangerous. Whatever happens the man’s a legend in our book. We’ll get there on the double to catch you doin’ the Super Bowl Shuffle any time, Jim.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |