It’s where Muhammad Ali’s undefeated record came to an end, where one of the country’s most iconic presidents was serenaded by one of the world’s most beloved women, and where animals that some consider to be mere pets are held up as champions. As anyone who works in front of an audience knows, you haven’t made it until you’ve played Madison Square Garden.

It was a terrible building. The old passenger depot for the New York and Harlem Railroad had seating for 10,000 but no roof, which made for a lot of sweaty people in New York City’s summers—and a lot of chattering teeth in winter. Still, the first Madison Square Garden had its charms. P.T. Barnum saw the potential in the “patched-up grimy, drafty, combustible, old shell” (as Harper’s Weekly called the building) and in the late 1800s opened “Barnum’s Monster Classical and Geological Hippodrome” on the corner of East 26th Street and Madison Avenue. The “Madison Square Garden” moniker came later, along with several reincarnations and an eventual move away from Madison Avenue. Today’s Madison Square Garden (“The Garden” to locals and “Garden IV” to historians) occupies the blocks along 8th Avenue between 31st and 33rd Streets. About the only thing it has in common with the first Garden is the train station connection, as the current venue sits atop Penn Station. Like its predecessors, today’s Garden has its problems. But as the premiere performance space of one of the world’s premiere cities, it remains the ultimate proving ground for any kind of performance or competition.

The building used for the first Madison Square Garden, as mentioned before, was a bit of a wreck. Still, the former railway depot occupied a nice piece of real estate adjacent to Madison Square Park, which itself was named for a cottage that had been built there in honor of President James Madison. Owner Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt leased the depot to Barnum, who converted it into an arena where he staged Classical Roman chariot races, circuses and other spectacles.

In 1876 the lease passed to Patrick Gilmore, a bandleader who renamed the building “Gilmore’s Garden” and then used it for all manner of events, including concerts, religious meetings, beauty pageants and flower shows. Under Gilmore’s tenure, the building also hosted the first Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show, an event that would become a Garden staple. It was a dog show official, W.M. Tileston, who next signed the lease. He expanded the venue to host sporting events such as tennis and horse riding, and built one of the country’s first indoor ice rinks on site. Tileston also boosted boxing, which had first come in under Gilmore and which was quite popular despite being illegal at the time. New York was the first state to legalize competitive boxing, in 1896. Prior to that, matches were staged as “exhibitions” in which fighters were presented as “professors” who gave “illustrated lectures on pugilism.” It was a ridiculous pretense but it satisfied the authorities, many of whom were attending the “lectures” themselves no doubt.

When the Commodore died in 1877, his grandson William Vanderbilt took over and two years later made a lasting contribution by renaming the venue “Madison Square Garden.” William also added track and field meets, the National Horse Show, a cycling velodrome and more boxing. The boxing included bouts with the legendary pugilist John L. Sullivan, who regularly sold out exhibitions during a four-year stint at the Garden that began in 1882. Barnum was still around as well, regularly exhibiting “Jumbo” the elephant, which he’d acquired from the London Zoo. Though a formidable venue, the lack of a roof eventually did it in with the public, and the first Garden was demolished in 1889.

The following year, the second Madison Square Garden opened on the same site. Final costs exceeded the then-fantastic sum of $3 million, but the price didn’t bother the new ownership group, which included the likes of J.P. Morgan, W.W. Astor, and Andrew Carnegie. For their money they got a modern Beaux-Arts gem with a strong Moorish influence. The Garden’s bell tower was modeled after the “Giralda,” the bell tower at the cathedral in Seville, Spain, that had been converted from the minaret of a mosque originally built on the cathedral’s site.

In addition to putting the exclamation point on the building’s character, the tower was also New York’s second-tallest building, at 32 stories. The main hall was the largest in the world at 350 feet by 200 feet, and the structure’s several theaters, concert halls, and main restaurant—the largest in New York, with seating for 1,500—meant it was one of the world’s premiere event spaces. Standing proudly atop Garden II was a statue of the goddess Diana sculpted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who also created Central Park’s sculpture of William Sherman and the “double eagle” U.S. $20 gold coin, still considered one of the most beautiful coins ever minted. Diana was popular—people even started referring to Madison Square Park as “Diana’s little park”—but, unfortunately, she was also huge: 18 feet tall and 1,800 pounds in weight. The fact that she was meant to spin with the wind didn’t help in terms of strength, and after her cloth cape was ripped off in a particularly strong breeze the statue was removed and installed atop a building in Chicago. Her luck didn’t get better, as Diana’s bottom half was subsequently destroyed in a fire, and the top half was eventually lost. A hollow (lighter) and smaller version replaced the original in 1893, and that statue now sits in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with a smaller example on display in the current Madison Square Garden.

Architect Stanford White designed Garden II and ultimately met his end there, shot down by millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw while enjoying a performance in the rooftop cabaret. Both men were notorious womanizers, and the shooting was related to Thaw’s wife (and White’s former lover), the actress Evelyn Nesbitt. Somewhat ironically, Thaw waited until the cabaret’s final song, “I Could Love A Million Girls,” then produced a pistol and shot White three times. It was just one more story added to the Garden’s lore, which also included the annual French Ball (a lavish event at the time), the 1924 Democratic Convention, and the first-ever indoor American-style football match. Boxing at the Garden continued as well, with the new facility seeing Jack Dempsey’s famous knockout of Bill Brennan in the 12th round of a 1920 fight, and hosting a full 32 world championship bouts between 1925 and 1945. In cycling (still massively popular at the time), the Garden saw a team track cycling event named for its first incarnation, “Madison.” Madison events are still held, and have been a regular fixture of the Summer Olympics since 2000. Despite appearing in a film (1924’s “Great White Way”) and its place at the forefront of New York’s social and performance scene, the beautiful Garden II was demolished in 1925 to make way for the New York Life Insurance Company’s new headquarters. It was the end of Garden II, but not the end of Madison Square Garden.

Madison Square Garden left Madison Avenue in 1925 and moved to the corner of 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets. From the start, Garden III was a bit of a bust. It was designed by Thomas Lamb, a respected theater architect, which seems surprising as most considered the building unattractive to look at and unpleasant to visit. It looked like a big, plain box, with none of the style or grandeur of Garden II. Interior sight lines were terrible, with views all but blocked for anyone seated behind the first row of the upper deck. Also, poor ventilation—combined with the then-popular and fashionable pursuit of smoking heavily—meant that anyone in the upper decks was also sitting in a brown cloud. Some of the building’s issues might be attributed to its rapid construction: 249 days from groundbreaking to opening. The man behind Garden III was boxing promoter Tex Rickard, who also has the distinction of naming the Garden’s hockey team, the New York Rangers. He enjoyed the play on words: “Tex’s Rangers”—get it? In any case, despite its many issues, Garden III carried New York from 1925 to 1968, and was the setting for many of the city’s (and country’s) storied moments.

Boxing, of course, factored into the Garden’s lineup, with the venue’s first bout happening a week before the official opening, and one of its most lauded battles occurring in 1941, when the then-record crowd of 23,190 people watched Fritzie Zivic beat Henry Armstrong. As mentioned, the New York Rangers started here and eventually won three Stanley Cups in the building, which they shared with the New York Americans, another hockey team, which suspended operations when America entered WWII. Following the war, efforts by Rickard and his partners ensured the Americans never re-formed.

Garden III also hosted the first-ever professional basketball game in 1925, between the Original Celtics and the Washington Palace Five (Celtics won, 35-31). The New York Knicks debuted here in 1946 but were hardly the headliners they are today, having to move their games to a nearby armory if an important college game wanted the Garden.

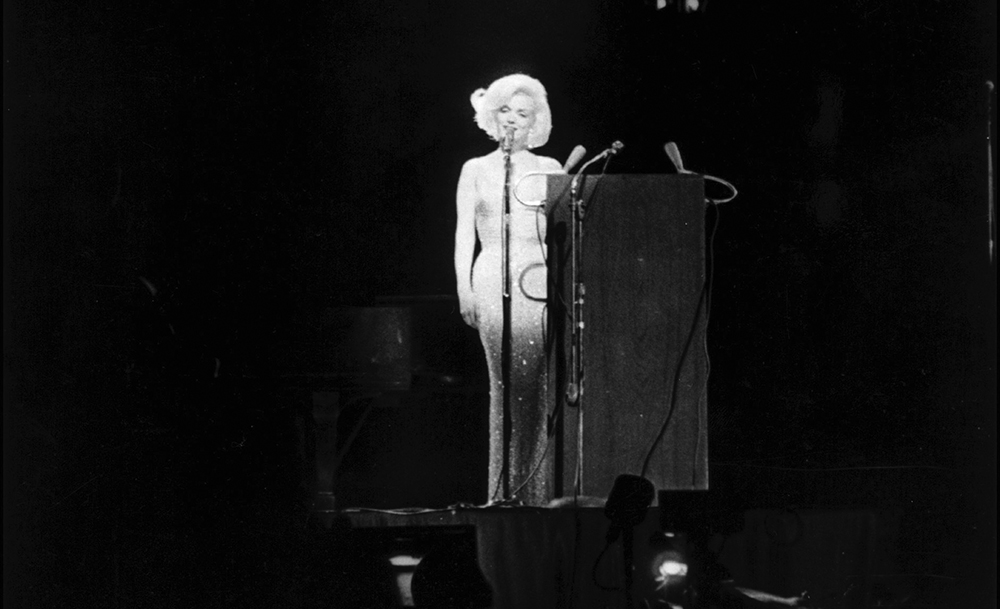

In 1937, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia spoke at a large “Boycott Nazi Germany” rally at the Garden. Two years later it was the Nazis’ turn, and the pro-Nazi “German American Bund” held its event, bringing a crowd of 20,000 to the Garden’s auditorium. (The group was outlawed two years later.) Evangelist Billy Graham held a rally here that ran every night for 16 weeks, Gene Autry hosted a rodeo here attended by 13,000, and in 1957 Marilyn Monroe appeared at the Garden riding an elephant for a party celebrating the film Around the World in 80 Days. Five years later she would make history at President John F. Kennedy’s Garden birthday party by serenading the President with a titillating version of “Happy Birthday to You,” the same year the final scene in The Manchurian Candidate was filmed here. Due, as ever, to revenue issues, in 1968 Garden III was torn down and the modern incarnation began.

Opened in 1968, the fourth Garden has survived longer than any of the others though, like the others, it’s no stranger to controversy. To make room for the massive structure New York’s Penn Station was torn down, destroying perhaps the city’s finest example of Beaux-Arts architecture and prompting the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Where the original Penn Station was heralded as a grand cathedral that served as many people’s first vision of New York, the current Penn Station—underneath Madison Square Garden—is mostly reviled for its cramped hallways, low ceilings and lack of aesthetics. As for the Garden itself, like its immediate predecessor it’s more functional than fashionable, and “functional” only begins to describe it. The Garden hosts more than 320 events per year, is the home of the Rangers, the Knicks and the WNBA’s New York Liberty, and still manages to provide a stage for some of the biggest political and sporting events in the world. Barnum would be happy to know that his circus still makes appearances, and the Westminster Kennel Club’s Dog Show is still here. Boxing fans revere the Garden as the site of the first Frazier–Ali bout (and many other legendary fights), basketball fans remember when the Knicks were on top, taking the 1970 championship here, and New York’s hockey fans were thrilled when the Rangers took their first championship here in what seemed like forever, in 1994.

For music, few venues on the planet have hosted more, or better, shows than the Garden. George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh, John Lennon’s final concert appearance, and The Concert for New York City (after the 9/11 attacks) were all here. Elton John has played the Garden 62 times, and declared it “my favorite venue in the whole world,” while Billy Joel played 12 performances in a row here in 2006 and announced that “Madison Square Garden is the center of the universe as far as I’m concerned.”

The Garden has been featured in far too many films to list; it’s hosted most of the world’s greatest performers and held many of the country’s premiere sports events. All of that said, it might follow suit with Gardens past and change locations at some point. Despite an $850-million renovation that’s underway (Phase I was just completed), current Garden leadership has said that it’s committed to a plan to relocate across the street, potentially utilizing property currently occupied by the James Farley Post Office. That building, which dates to 1912, is on the National Register of Historic Places, so the Garden might be staying put for a while. But wherever it is, Madison Square Garden is New York’s place to see and to be seen. If you can make it here, you really can make it anywhere.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |