They call it the Golden Dram, partly because of its tantalizing, golden, honeyed color but also because gold deposits have been found in the Pitilie Burn, the water source for the Home of Dewar’s, the Aberfeldy distillery in central Scotland. Robin Barwick paid a visit to learn how the Aberfeldy malt remains at the heart of the famous Dewar’s line of Scotch whisky

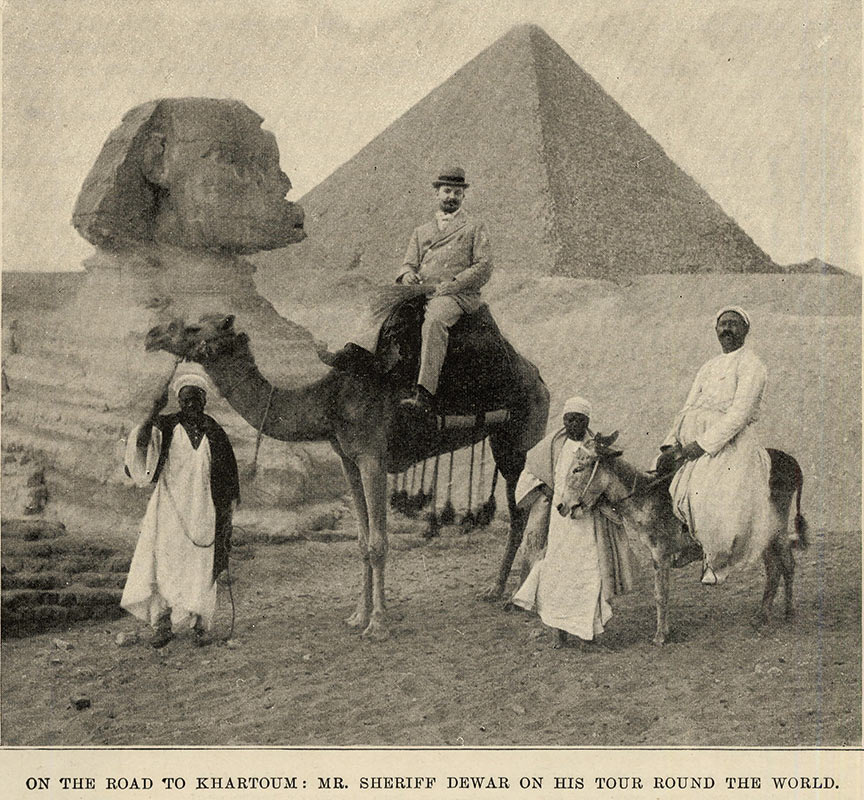

It was in 1885 when 21-year-old Tommy Dewar first made the daunting journey from Perth, in central Scotland, 450 miles due south to London.

Tommy’s older brother John Alexander was running the whisky business established in 1846 by their late father John. It had begun as a merchant of wine and spirits before the Dewar’s house blend of whisky began to take hold. Founding father John Dewar established a strong provincial business but his sons saw potential far beyond the shops, pubs and hotels of Scotland.

John Alexander held a steady hand on the tiller while Tommy’s youthful, bold exuberance and ready wit was sent out to seek new sales.

So onto the London train Tommy climbed, heading into the unknown and representing the biggest marketing gamble this young company had ever made. A prolific writer and diarist, Tommy would later write:

I arrived in London armed with two cards of introduction to prospective customers. At the first address I discovered the man had died—I thought then to evade me—and the other had gone bankrupt. The whole goodwill of my entire business was shattered in one morning. Then I felt the terrible loneliness of a stranger in a city with millions of inhabitants.

Tommy Dewar would receive no lucky break in London in 1885, but he spent the next five years knocking on doors, distributing samples, establishing contacts and picking up odd, small sales where he could. By 1890 the UK market for quality Scotch was picking up and so were Tommy’s orders, to the point where Dewar’s took on its own distillery for the first time, near Perth.

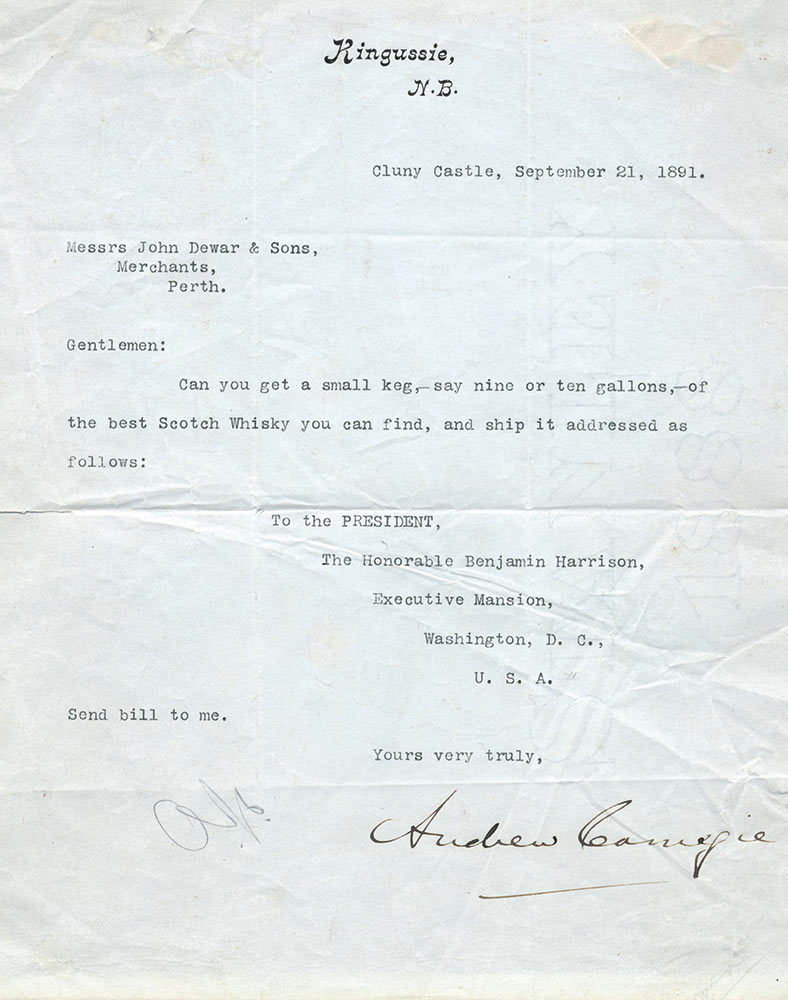

Just as Dewar’s UK business was growing the Perth office received an unexpected letter from Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, from his summer retreat of that time, Cluny Castle, to the west of Aberdeen (this was the era before Carnegie bought and restored medieval Skibo Castle in the Highlands to a state of striking majesty). At this time Carnegie—widely considered to be the world’s richest man—was the most powerful figure in the booming US steel industry, and he personally wrote to Dewar’s asking that a “small keg” of the “best Scotch whisky you can find” be delivered to: “The President, The Honorable Benjamin Harrison, Executive Mansion, Washington D.C.”, who was a close ally of Carnegie’s.

This was a more explosive introduction to the American market than even Tommy’s vivid imagination could have mustered. When the so-ordered keg of Dewar’s arrived at the docks in New York uproar spread through the American newspapers that President Harrison was not supporting American-distilled Bourbon and rye whiskies. The President was merely the innocent recipient of the keg but while he took the heat Dewar’s was flooded with American orders.

Mischief might have motivated Carnegie’s gift because Harrison’s four-year stint as President was famed for the McKinley Tariff that he saw through Congress in 1890, which raised the average duty on imports to almost 50 per cent, in a move to protect domestic industry from foreign competition. A keg of Dewar’s had never been strapped with more irony, while the McKinley Tariff ultimately did few favors for Harrison’s political career as he would lose the 1892 election to Grover Cleveland, who restored lower tariffs in 1894.

In a bid to capitalize on this new-found American demand, intrepid traveller Tommy headed west to the States to establish a new distribution network, although obstacles he came up against did include a number of prohibition states. Tommy recounts a particular shop visit:

‘Do you sell whisky?’

‘Are you sick mister, or got a medical certificate?’

‘No.’

‘Then I can’t do it. See, this is a prohibition state so I can’t sell it, but I reckon our cholera mixture’ll about fix you. Try a bottle of that.’

To my great astonishment I received a very familiar bottle labelled on one side, ‘Cholera Mixture: a wine-glassful once every two hours’… the other side [had] the well-known label of a Scotch distillers, whose name modesty requires me to suppress.

The ease with which a man could navigate around prohibition was one thing, while the recommended “wine-glassful once every two hours” would have underpinned a brisk trade in repeat prescriptions.

The first Dewar’s US office would soon open in New York and so fast did international demand grow that Dewar’s needed to build a brand new distillery. The perfect spot was found outside the village of Aberfeldy and the construction of one of Scotland’s very finest distilleries spurred Dewar’s to become one of the top-selling whisky companies of all time.

So wrote Scottish bard Robert Burns in 1787:

Bonie lassie, will ye go

To the birks of Aberfeldy!

Now Simmer blinks on flowery braes,

And o’er the crystal streamlets plays;

Come let us spend the lightsome days,

In the birks of Aberfeldy.

These seductive lines are taken from the song The Birks of Aberfeldy (with “birks” meaning birch trees) and visitors to the Aberfeldy distillery, set back into a wooded hillside along the River Tay valley, can immediately appreciate Burns’ sentiments. The village, distillery and birch-filled woodlands here remain virtually untouched over the centuries and through the 120 years since the first wash was distilled at Aberfeldy in 1898, using water from the Pitilie Burn that flows past the distillery and into the Tay. Right in the heart of Scotland, 75 miles northwest of Edinburgh, Aberfeldy is far off the Scottish mainstream yet it is core to Scotland’s whisky heritage.

The Aberfeldy distillery began producing a single malt that immediately provided the backbone to all Dewar’s blends—in the 19th century and through to the modern day—and which has in recent years become prominent as a single malt in its own, delicate and distinctive right. A dram not to be rushed, Aberfeldy is patiently fermented for 72 hours to help bring out its honey notes, when the industry standard is around 50 hours.

“I like to think that Aberfeldy was the inspiration behind Dewar’s White Label,” starts Stephanie MacLeod, who is only the seventh Master Blender to serve Dewar’s over 172 years of production, and she is the first woman to hold the post, which she has done since 2006. “Aberfeldy has honeyed sweetness and floral notes but there is a little bit of peat smoke that comes through at the end, so White Label very much mirrors Aberfeldy.”

Dewar’s White label has been the cornerstone of Dewar’s success—a distinct blend characterized by a swirl of honey with a sprig of Scottish heather. It is rich, golden and warm, yet offers a clean finish and only subtle sweetness, with fresh vanilla and a slice of pear.

“White Label is very approachable but it has a backbone to it and lovely fruity notes that come through, and baked cereals,” adds MacLeod. “White Label is easy drinking but also interesting, and it does not get lost in a cocktail.”

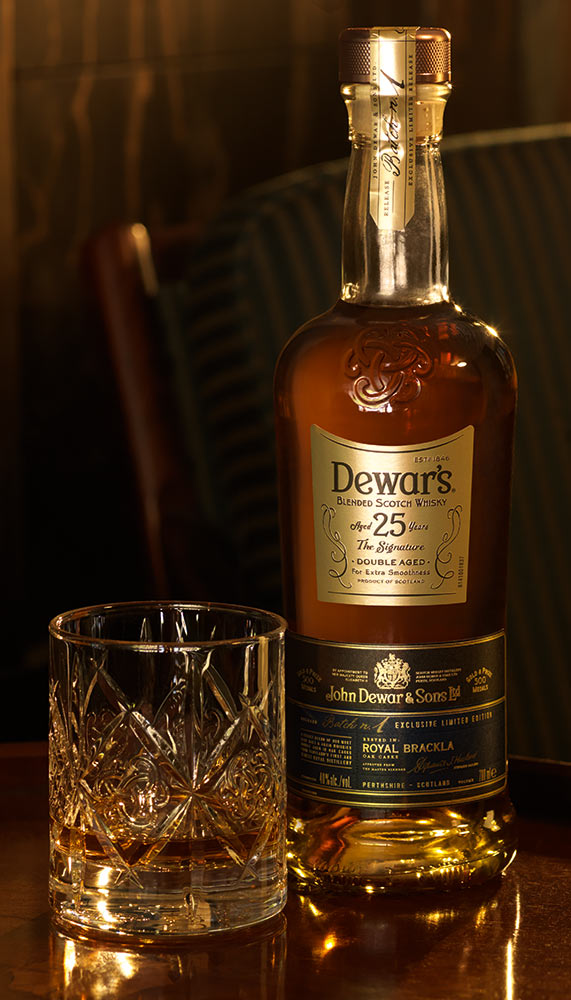

The depth of the Dewar’s line of blended whiskies shifts gears through 12 Years Old, 15 Years Old and 18 Years Old, and now a bottle of Dewar’s 25 Years Old is available for the Dewar’s connoisseur.

“Dewar’s 25 really adds another element,” says MacLeod, “so there are lots of ripe berry notes and peaches and almond coming through and cherry stone, and notes of lime and freshness and a hint of freshly cut grass, along with the lovely coconut notes that you associate with an aged whisky. We also take an extra step with 25, so after it has been double-aged [as all Dewar’s Whiskys are] we put it into Royal Brackla casks to add a regal finish. Royal Brackla is a very soft and accommodating malt whisky so it seems the perfect resting place for Dewar’s 25.”

But to really appreciate the full flavors of Dewar’s you must head to the “Birks of Aberfeldy” in person, where an award-winning visitor experience at the distillery sets the industry standard and brings the Dewar’s colorful history to life. Complete with a spacious lounge and bar and the full array of Dewar’s blends and malts ready for tasting and comparing, Aberfeldy Distillery is all about interaction. A spacious museum partly modelled on one of Tommy’s lavish studies is flanked by a gallery of Dewar’s advertising posters over the decades, which provides a fascinating insight into Tommy’s conviction to “Keep advertising and advertising will keep you”, while visitors are also invited to don a white lab coat and concoct their own whisky blend (warning: it’s harder than it seems to create something palatable).

A trip to Aberfeldy should follow the same rules as making whisky and drinking it—it is best when time can be devoted to it. To borrow more wise words from Tommy Dewar, “The only thing you get in a hurry is trouble”.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |