Ah, Henry Jennings, who could resist? Eleven Spanish ships bound for Spain laden with silver, gold and jewels, sunk in a hurricane in 1715 in the shallow waters off the Florida coast. And the treasure, what the Spanish and their Indian pearl divers had salvaged, hastily piled on the sand in that camp at Palma de Ayz, awaiting transport to Havana. Three ships, maybe 300 men, and the camp was overwhelmed. You stole 10 years’ worth of wages off the beach that day, but it was nothing compared to what remained on the sea floor, still waiting to be recovered…

Over a billion,” says Taffi Fisher Abt, daughter of Mel Fisher, perhaps the most successful treasure hunter in history.

“There’s a couple hundred million of stuff left to find that’s listed on the manifest. And not on the manifest, the contraband? Over a billion. It’s a very worthy target.”

Over a billion. And Taffi is only speculating about what’s left on the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, the Spanish galleon her dad found in July of 1985. By most accounts Fisher’s discovery was worth $450 million and, as Taffi pointed out, it comprised just part of the Atocha’s cargo. If one adds up the treasure in all of the shipwrecks around the world (and there are thought to be millions of wrecks), it’s estimated that there’s more than $60 billion sitting at the bottom of the sea. All you have to do is go and get it.

Of course that could take a lifetime, and it’s almost certain to take a lot of money. Treasure hunting is one thing, treasure recovery is another; there are boats and equipment to hire, people to pay and maybe years of uncompensated searching with no guaranteed return. If you do find treasure, you’ll have to deal with a government or two (depending on where you find it), and with other treasure hunters who might learn of your discovery. And then there’s the difficult task of turning treasure into actual money, a sort of reverse alchemy that must be performed because, as it turns out, you can’t buy groceries with a 17th century ruby-crusted chalice.

Doing as much to dissuade as to entice are the odds, which decidedly are not in a treasure hunter’s favor. For every Mel Fisher there are millions of failed adventurers, romantics, scoundrels and madmen, and there are examples of each of those who’ve lost relationships, family fortunes, and even their lives in pursuit of treasure. But who knows: if you’re lucky—really lucky—like Henry Jennings did, you just might find gold sitting on a beach in Florida.

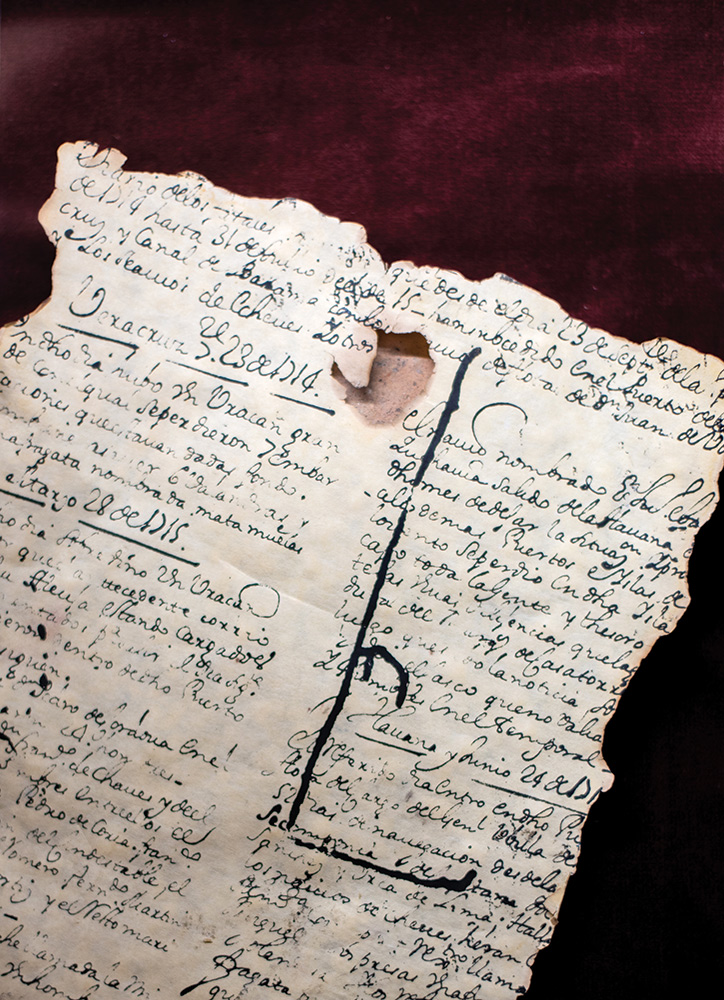

Jennings was a rich kid Englishman and ship’s captain from Bermuda who, for whatever reason, decided to have a go at piracy. Like many 18th century privateers, he was granted a commission by the English government to profit as he liked at the expense of England’s enemies, namely Spain. And so when in November of 1715 word of a potential windfall reached Jennings in Jamaica—11 Spanish treasure galleons down in a hurricane near what is today Vero Beach—it lit a spark.

Jennings sailed his ship Bersheba north as quickly as he could, arrived in early 1716 and committed his first act of piracy by attacking the Spanish and stealing their salvaged treasure, which they’d piled on the beach in anticipation of shipment to Havana. With him were Charles Vane, Benjamin Hornigold and Samuel “Black Sam” Bellamy, all of whom went on to become noted pirates. But not all treasure hunters are pirates, and today you’re more likely to see metal-detecting optimists stepping over sunbathers than you are marauders storming down the sand.

One of those optimists was Kip Wagner, a south Florida contractor who, in the 1950s, met a friend at a pub, had a few beers, and was told about coins washing up on beaches after storms. He decided to have a look, and over the next decade or so he found a number of “pieces of eight” on the beaches near his home in the Vero Beach area. Critically, in 1959 he identified them as being from what is now called “The 1715 Treasure Fleet.” It wasn’t long before Wagner found the site of the Spanish camp that Jennings had raided, and then he found a shallow water wreck site, complete with cannons and an anchor. Deciding to go into the treasure hunting business in earnest, Wagner leased a 50-mile area for salvage from the State of Florida and formed The Real Eight Company in hopes of striking it rich. He and his friends worked several locations over the years, but with no one able to commit full-time to the search progress was slow—and then Mel Fisher came along.

Fisher was an unlikely but driven SCUBA diver, hailing from Indiana where, at the age of 11, Taffi says he built his first diving rig by affixing a bucket to a bicycle pump and submerging himself in Lake Michigan (his friend pumped-in the air).

He served in the Army Corps of Engineers during WWII, then moved to Chicago and Denver until landing in Torrance, California, with his parents, opening a chicken ranch and continuing to pursue his love of diving. Eventually he married a girl from Montana named Dolores, who said she fell in love with Mel and with the ocean at the same time, and the two opened what might have been the world’s first dive shop, “Mel’s Aqua Shop,” in Redondo Beach. It could be said that nearly everything Fisher earned came from the sea, as the shop was built one wall at a time using money from the sale of lobsters, which the couple caught off the California coast. Returning from a Caribbean trip in 1962, the Fishers stopped in Florida, met Kip Wagner, and agreed to spend a full year with no pay diving one of Wagner’s sites. Mel convinced seven others to join him, sold the dive shop, and they set to work. After 360 days with not much to show for their efforts, an invention of Mel’s—“the mailbox”—changed everything. It’s basically a giant elbow-shaped tube lowered over the stern to cover a boat’s propellers. The boat is anchored, the engines engaged, and the prop wash forces clear water down to the bottom to displace murky water so that divers can see. It also has the effect of clearing sand, and on its first day of use it quickly revealed 1,033 gold coins. As Mel said at the time, “Once you have seen the ocean bottom paved with gold, you’ll never forget it.”

Fisher and his team continued to salvage the 1715 Fleet, but winter in the Atlantic made work tough so he turned to searching for the Atocha in the waters off the Florida Keys. The search would cost him plenty: 16 years of hard times and the life of his son Dirk, who died with his wife, Angel, and a diver when their boat capsized one night. Still, persistent and driven, Fisher would set out each day declaring “Today’s the day!” until one day when, finally, it was.

“My brother called him and said, ‘Dad, put the charts away—we’ve got it!,” Taffi recalls. “‘It’s here, piles of silver bars, chests of coins, gold bars… The mother lode.’ All hell broke loose after that. Because we were always working on a shoestring financially, man oh man was it crazy. All of a sudden everybody wanted to shake my dad’s hand, invest money, go out and dive the wreck. There were all these reporters, front page of every magazine and all over Europe and everywhere. He was really famous suddenly, super famous.”

The estimated $450 million worth of treasure had to be pulled from the ocean and transported to a museum Fisher had set up in Key West. It wasn’t easy, as Taffi points out: “We had four boats out there piling silver bars on their decks. Each bar is about 90 pounds troy (roughly 75lbs), and that’s heavy,” she says. “You’d bring it up from the bottom with a rope and a basket, then you’d hand that up the dive ladder to a guy who puts it on deck. When you get 100 70lb silver bars on your boat, you think ‘we might sink!’ And so you’d put half on one side and half on the other to balance it out and then you’d make a trip in, offload and come back out. At the dock you’d hand it up to a guy on the dock, walk down the dock, we’d load it in the back of a pickup truck and then drive to the museum. Unload it, take it to the third floor where a conservation lab was, then you’d put them in stacks of 10. Then we thought, ‘the floor’s gonna collapse!’ So we started putting them in other spots around the museum so it wasn’t all in one spot; we didn’t want to collapse the building. How many? We found almost 1,000.”

Today each of those can be worth about $100,000, she says. They also found incredibly rare emeralds from Colombia, gold coins, long lengths of gold chains—one was 67’ long—and chests full of pieces of eight. The wood on the chests was long gone, but the silver coins would be fused together in giant blocks due to the saltwater. The individual coins now sell for anywhere between $1,000 and many tens of thousands, depending on where they were minted and other factors.

“We found 100,000 pieces of eight,” Taffi says. “Like a silver dollar from the 1600s. Back then it could buy a month’s worth of groceries, it was a month’s salary for a sailor. But today we can’t take this and pay our electric bill or buy groceries. So what do we do?”

And here Taffi hits on a rough spot in the treasure trade, for “treasure” does not mean “cash,” and it can be tough to turn the former into the latter.

“When my grandfather found the mother lode in 1985, I was just 1 [year old],” says Nichole Johanson, Taffi’s daughter, who runs the Mel Fisher Treasures museum and gift shop in Sebastian, Florida, and helps with the family treasure-hunting business, which continues. “There were a lot of misconceptions that we’re rich, we’re millionaires, but it’s just that—a misconception. We’re treasure rich but cash poor. You can’t pay your electric bill with a silver bar.”

Or your taxes, exactly, but that’s not to say the government doesn’t want its share. Fisher gave the State of Florida portions of his finds up until the Atocha, when a legal battle began between the two. After Florida lost its claim to Fisher’s finds in court, it appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately found in Fisher’s favor, awarding him ownership of the Atocha and its sister ship, the Margarita. Today, part of the treasure is available to anyone who wants to purchase it, on sale at the Fisher museums in Sebastian and Key West and online. Some gets donated, and a fair portion was and is distributed to investors who supported (and support) its finding. Every now and then a collector will buy a special piece (there’s a necklace in the Sebastian museum that’s currently on sale for $768,000; see photo at right) but otherwise the treasure remains, not paying bills.

Despite the pitfalls, Johanson says, people won’t stop looking for treasure: “Everybody wants to be a treasure hunter, there’s so much romance even with the phrase ‘treasure hunter.’ Especially when you hear about big finds, you get a lot of calls, ‘I want to be a treasure hunter, how do I do that?’ The successful ones are the ones that have that perseverance to continue, because let me tell you something: there’s a lot more empty holes dug than there are holes with treasure in them. It’s hot, backbreaking work, sometimes it can be devastating. There are a lot of people who’ve come and gone; the ones who come and stay are the ones who can endure the heartbreaks.”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |