Often overshadowed by the luster of their events, the figures atop awards are there for a reason

Among the many gilded personalities one might encounter in the course of a life, it is hoped that a few might be those atop awards. Victory in competition is sweet indeed, and more’s the pleasure when a shining trophy is firmly in hand, raised high for all to see. But who is it, exactly, that winners are hoisting aloft? As it turns out, in golf, horse racing, auto racing and more, the figures memorialized on awards are rarely chosen at random. Many earned their perches, and not easily. Here, then, are just a few of their stories…

Winner of the Indianapolis 500

Of singular design—some would say peculiar—the Borg-Warner Trophy is one of the most coveted awards in motorsports. Since its introduction by Eddie Rickenbacker in 1936 it has been awarded to winners of the Indianapolis 500, and since it was first awarded each winner has had his face sculpted in bas-relief on the trophy’s side. This presents an obvious problem as the trophy’s original size accommodated only 70 winners. Hence, in 1986 a larger base was added to accommodate more, and in 2004 the same operation was performed again. Currently there’s enough room to hold winners through 2033, at which point the trophy presumably will grow even taller and heftier than its current size of 5’ 4” and 153 pounds. While the trophy is displayed trackside during the race and then placed on the rear of the winner’s car after it pulls into Victory Lane (a tradition that dates to the 1911 debut of the race), winners don’t get to take the actual Borg-Warner home. More conveniently, they receive a “Baby Borg,” 18 inches tall and significantly less adorned. Lacking the winners’ faces, it does bear the same figure on top of a man waving a checkered flag. And if you’re wondering why the trophy is most often photographed head-on with the flagman’s arm covering his business, it’s because he was sculpted in the tradition of Greek athletes. That is to say, he’s naked.

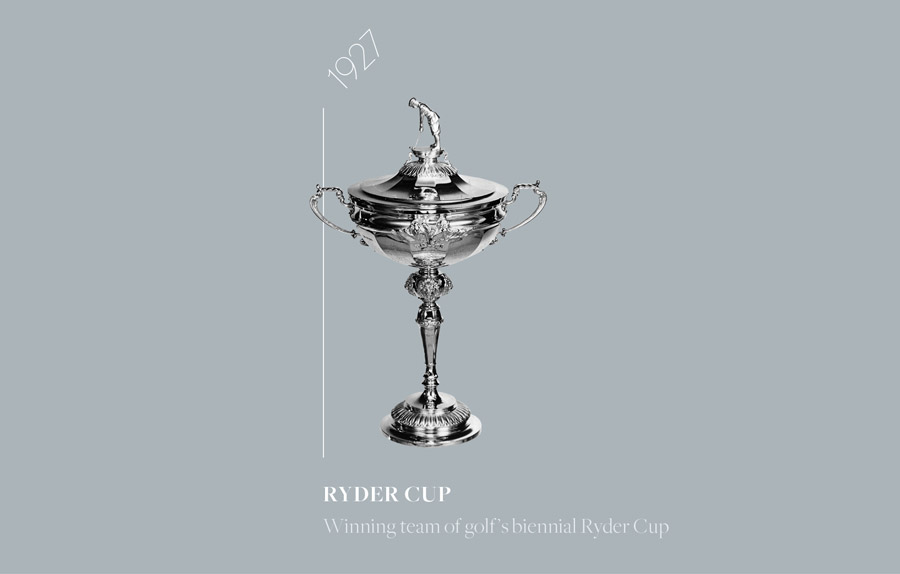

Winning team at the Ryder Cup golf matches

Many have gazed upon his face, but few will know his name. Legend has it that gardner, chauffeur, golfer and golf instructor, Samuel Ryder’s friend Abe Mitchell has the honor of topping one of golf’s most iconic trophies: the Ryder Cup. Harold Abraham Mitchell (known as “Abe”) was born in 1907 to an unwed mother, who was a caddie at England’s Royal Ashdown Forest Golf Club. Mitchell spent much of his childhood there, learning golf partly by watching expert club-maker and club pro Jack Rowe. Decidedly among the lower classes, Mitchell wasn’t able to play Royal Ashdown Forest proper, but he was able to join an auxiliary club that allowed access for those who lived in the club’s vicinity. While there, serving in a variety of odd job positions, he secured the financial backing necessary to compete in amateur tournaments, which he did until turning pro in 1913. Finishing fourth behind Harry Vardon at the 1914 [British] Open Championship, Mitchell’s burgeoning career was interrupted by the first World War, in which he served as a gunner. When the war ended, Mitchell returned to golf and quickly won the 1919 News of the World Matchplay Tournament. Despite never securing an Open Championship victory, Mitchell became somewhat of a crowd favorite. His popularity led to exhibition matches in the United States and appearances in the U.S. Open, all of which contributed to earnings that were likely far beyond his boyhood dreams. In 1923 Mitchell took a job as personal golf tutor for wealthy seed merchant Samuel Ryder, who eventually proposed a golf tournament between Great Britain and America. In 1926, the year before the first official Ryder Cup was played, Americans Walter Hagen, Tommy Armour, Jim Barnes and Fred McLeod faced off against Ted Ray, Abe Mitchell and two English players at Wentworth in the week prior to the Open Championship. Hagen was four down to Mitchell at the end of the first day and, it’s reported, intentionally arrived 30 minutes late on the second day to throw the notoriously high-strung Mitchell off his game. It worked, Mitchell’s game fell apart and Ryder, reportedly shocked at the American’s gamesmanship, decided Mitchell would adorn the trophy he was creating for the transatlantic matches. The following year, after the first official Ryder Cup matches, Ryder’s trophy was presented and Mitchell, having began life as low as one could be, was elevated to the greatest heights of golfing glory.

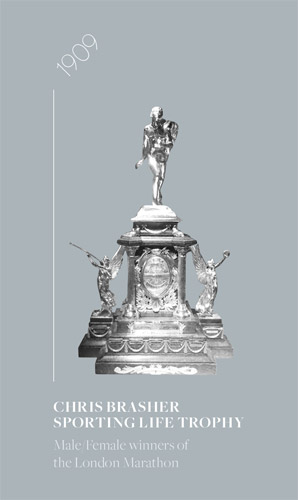

Male & female winners of the London Marathon

It’s one of the most coveted awards (and likely the most beautiful) in the sport of long-distance running. It’s also among the few trophies to be created for one event and now awarded for another. Commissioned in 1909 by English publication The Sporting Life to serve as an award for London’s Polytechnic Marathon, it cost £500 to make, more than $80,000 in today’s money. “The Poly,” as the race became known, ran from 1909 to 1996 and was the first marathon to be routinely run over 26 miles, 385 yards, which is now the global standard. The figure atop the trophy is Pheidippides, the heroic Ancient Greek courier who, as it is held, ran roughly 26 miles to Athens from a battlefield near the town of Marathon to deliver news of a victory over the Persians. He’d run more than 175 miles in two days, coordinating military assistance from Sparta, and after covering the last stretch he supposedly collapsed and died, inspiring the modern marathon race. The trophy’s history gets a bit muddled in the decades after 1961, the year The Sporting Life pulled its sponsorship, with ownership questions arising among the race’s organizing Polytechnic Harriers club and the Mirror Group, which purchased The Sporting Life. After being stored alternately at the Harriers’ clubhouse, the Victoria and Albert Museum and, unfittingly, in someone’s basement following a post-race disappearance in the 1980s, in 1994 the trophy was formally claimed by the Mirror Group as an item on permanent loan by them to the London Marathon, a separate event that began in 1981 and which quickly replaced The Poly as the capital city’s preeminent foot race. At the time of its demise in 1996, The Poly had seen more world records and had been run over 26.2 miles more often than any other marathon in the world. If nothing else, its legacy is preserved in the magnificent Sporting Life Trophy, to which Olympian and London Marathon founder Chris Brasher’s name was added in 2003.

Winners of NHRA national events

Drag racing reached its peak of popularity in the 1960s, when The Wally Parks Trophy first emerged. Parks founded the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) in 1951 in an effort to keep kids from racing on local roads. The trophy that bears his name didn’t appear until the end of the 1960s, with “The Wally” first being awarded in 1969 to winners of NHRA national events. Still the most coveted and prestigious NHRA award, the trophy depicts not Parks but Top Gas racer Jack Jones. In the June 30 edition of National Dragster magazine, Jones said, “Believe it or not, Wally Parks called me and asked if I’d do him a favor, pose for pictures that would be used as models for the trophy.” The photo shoot was handled at California’s Pomona Raceway in 1969. Speaking to the Associated Press in August of 1970 at the age of 29, Jones hinted at the grueling life of a professional drag racer: “There are things that tear your soul,” he was quoted as saying in South Carolina’s Spartanburg Herald-Journal, “like when something goes wrong with the car at the starting line. Or when you get caught napping in a situation you’ve gone through 1,000 times. Or when a good friend wrecks and his life’s savings go down the drain with his car. Sometimes you wonder…”

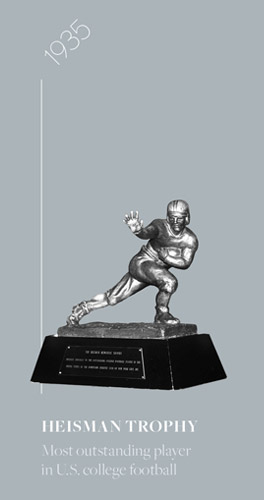

Most outstanding player in U.S. college football

John Heisman was a lot more than a football player. Also a head coach in football, basketball and baseball, Heisman ultimately served as Athletic Director of New York’s iconic Downtown Athletic Club, which was open from 1929 until 2001, when it suffered bankruptcy in the wake of the September 11 attacks (it was less than half a mile from the World Trade Center and suffered damage and extended closure). From 1937 through 2000, the Club was where the Heisman Memorial Trophy Award was presented to the country’s most outstanding college football player, but the statue that bears Heisman’s name does not bear his likeness. That honor goes to Ed Smith, who was a friend of sculptor Frank Eliscu. Smith played on the now-defunct New York University football team in 1934 before turning pro, and posed for the statue in 1935. As the story goes, he brought his cleats, uniform and a football to Eliscu’s studio before casually striking one of the most iconic (and imitated) poses in sports. Smith’s place in history remained a mystery—even to him—until 1982, when a documentary filmmaker learned the truth. Ultimately, Smith was honored with a Heisman of his own. “I was just doing a favor for a friend,” he later said.

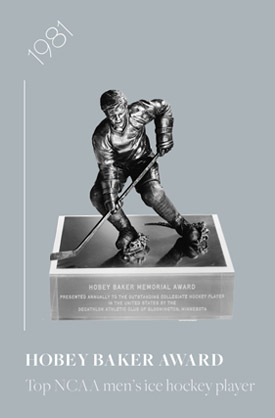

Top NCAA men’s ice hockey player

Presented to the top men’s college ice hockey player, the Hobey Baker Award is named for a WWI veteran who many consider to be the first American ice hockey star. Since the award’s inception in 1981 it has also indirectly memorialized one of the greatest hockey victories: the 1980 U.S. Olympic “Miracle on Ice” victory over the Soviet Union. The model for the trophy is Steve Christoff, who played on the “miracle” team and for the University of Minnesota before eventually joining the NHL. More than 50 different skating poses were captured in photos, from which one was chosen and sculpted by Bill Mack, who also sculpted the “Walking Man” statue at Hazeltine National Golf Club.

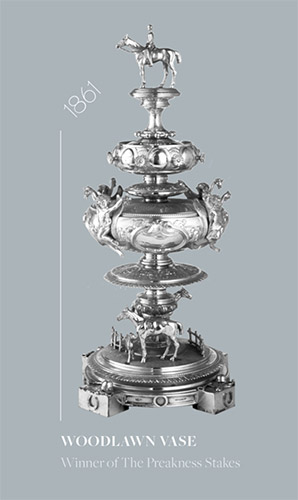

Winner of The Preakness Stakes

From his perch atop the Woodlawn Vase, Lexington the horse has seen a lot of history. Sire to Preakness, for which the second leg of Thoroughbred racing’s Triple Crown is named, the real Lexington belonged to Capt. T.G. Moore, who’s mare, Mollie Jackson, was the first to win the trophy in 1861.

The year before, the now defunct Woodlawn Racing Association commissioned Tiffany & Co. to craft the award, a stunning prize made of nearly 30 pounds of sterling silver, roughly 36 inches high and now reportedly worth as much as $4 million.

Today it spends most of the year at the Baltimore Museum of Art, with white-gloved members of the Maryland National Guard delivering it to Pimlico Racecourse for the annual running of The Preakness Stakes.

That it survived so long is a credit to the numerous families and organizations that have sponsored it—it was the award for races in Kentucky, suburban New York, New Jersey and Coney Island before finding a home with the Maryland Jockey Club in 1917.

Moore, perhaps, deserves credit as well: during the Civil War, he buried it in the dirt at Woodlawn Farm in Kentucky to save it from Union Soldiers, who he feared would melt it down. A staunch Southerner, Moore also hid his horse Lexington (which ironically had sired General Ulysses S. Grant’s favorite horse, Cincinnati) to prevent him from being commissioned for battle. Lexington—named North America’s leading sire 16 times—died of natural causes in 1875 and was buried in a coffin at Woodlawn Farm. Three years later he was dug up and donated to the Smithsonian, but after a time the organization simply put him in storage. In 2010 his bones were rediscovered and shipped to the International Museum of the Horse at Kentucky Horse Park, which reassembled him and which now displays his skeleton. Perhaps his best-known progeny, Preakness, had a similarly dark end: he was sold to the English Duke of Hamilton, who later shot and killed the horse in a rage.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |