Arnold Palmer claimed seven major victories between 1958 and 1964. Both his first and last came at the Masters, but they were very different successes. One was a dogfight, the other almost a cakewalk. Looking back, these parallel triumphs at Augusta National sum up Palmer to a tee—one part hewn out of doggedness in adversity, the other gilded with serenity.

Arnold Palmer enjoyed a near-lifelong love affair with Augusta National. Its golfing and floral attractions remained dear to him from the moment he first cast eyes on Bobby Jones’ pride and joy.

In total, Palmer donned four Green Jackets between 1958 and 1964, and he probably would have pulled on a few more along the way if fate had really played into his hands. But in repose, he was happy to consider his four victories among the azaleas and dogwood of deepest Georgia, especially as each of those titles resulted not just from consummate skill but from the raw grit inherited from his father Deacon.

Palmer made his Masters debut in 1955, the year after he won the U.S. Amateur title. That feat earned him the invitation to Augusta and he finished in a respectable tie for 10th. At the time, this was a mere footnote after Cary Middlecoff had triumphed by seven shots from Ben Hogan, with Sam Snead third.

Palmer’s recollection of the moment he and his wife Winnie first drove down Magnolia Lane in their two-door, coral-pink Ford is eloquently recorded in his autobiography, A Golfer’s Life. “I’d never seen a place that looked so beautiful, so well manicured, and so purely devoted to golf, as beautiful as an antebellum estate, as quiet as a church… I felt a powerful thrill and an unexpected kinship with the place.”

That kinship wasn’t particularly in evidence when he limped home in 21st place on his second appearance in 1956, but 12 months later, when he tied for seventh, the omens were inescapable. By then, Palmer had worked out where to position his drives so he could hold the greens despite his low ball flight, and the following year he claimed his first Masters, his first major. Golf was never the same again.

For the final round in 1958, Palmer, joint leader on 211, was paired with Ken Venturi. Even though a dozen players were grouped between 211 and 215 at the start of play, by the time Palmer and Venturi arrived on the 12th tee it seemed likely the winner of their duel would claim the title.

Palmer led Venturi by a solitary shot as they prepared to play this iconic short hole that to this day still measures a mere 155 yards from the back tee. True to Sunday tradition at the Masters, the pin was positioned treacherously in the far right corner of the green, and also in keeping with custom, the wind was gusting and swirling.

Both tee shots sailed over the shallow putting surface and into the bank behind. Venturi’s ball kicked down to the edge of the green, whence he two-putted. However, Palmer’s ball was embedded in the bank. It had rained heavily during the night and early morning and play that day was subject to wet-weather rules (lifting, cleaning and placing).

Following an animated discussion with a rules official Palmer was refused a drop, so he played the plugged ball and shifted it 18 inches. After chipping near the cup, only to miss the subsequent short putt, he returned to where his ball had been plugged and dropped over his shoulder—in defiance of the instructions Palmer had been given. His ball rolled down the slope a little, so he placed it near the pitch-mark, chipped stone-dead and this time holed the putt for a three. The question now was, had Palmer scored three or five? If three, he led by one; if five, he trailed Venturi by one.

“I’m sure there were plenty of people in the gallery who were certain they’d just watched Arnold Palmer disqualify himself from the Masters”

This question was still hanging when Palmer struck a 3-wood second shot to the back of the green on the par-5 13th and holed the 20-foot putt for an eagle three. Two holes later he received word from Jones that his three at 12 would stand. “I’m sure there were plenty of people in the gallery who were certain they’d just watched Arnold Palmer disqualify himself from the Masters,” he said. “But I knew the rule and believed I was within my rights to do what I had done.”

Despite that reprieve and the blow it represented to Venturi, Palmer still required a birdie three up the 18th to claim the Green Jacket. He duly delivered and won by a single shot from defending champion Doug Ford and Fred Hawkins, while Venturi ultimately tied fourth with Stan Leonard, a further stroke adrift.

“I was so tense and focused, I don’t even remember the walk up 18,” Palmer confessed.

In 1959, Palmer was hot property and the red-hot favorite. After three rounds he was tied for the lead with Leonard. By the time he arrived at the self-same 12th tee, he had his nose in front, but fate at Augusta National proved a cruel equalizer and he walked off the green with a triple-bogey six after dumping his tee shot in the water.

He still had a shout after birdying the 15th, but short putts missed on the closing two greens left him two shots behind Art Wall and one behind Middlecoff. “My disappointment was immense. I’d had the tournament in my grasp but had been unable to close,” he reflected ruefully.

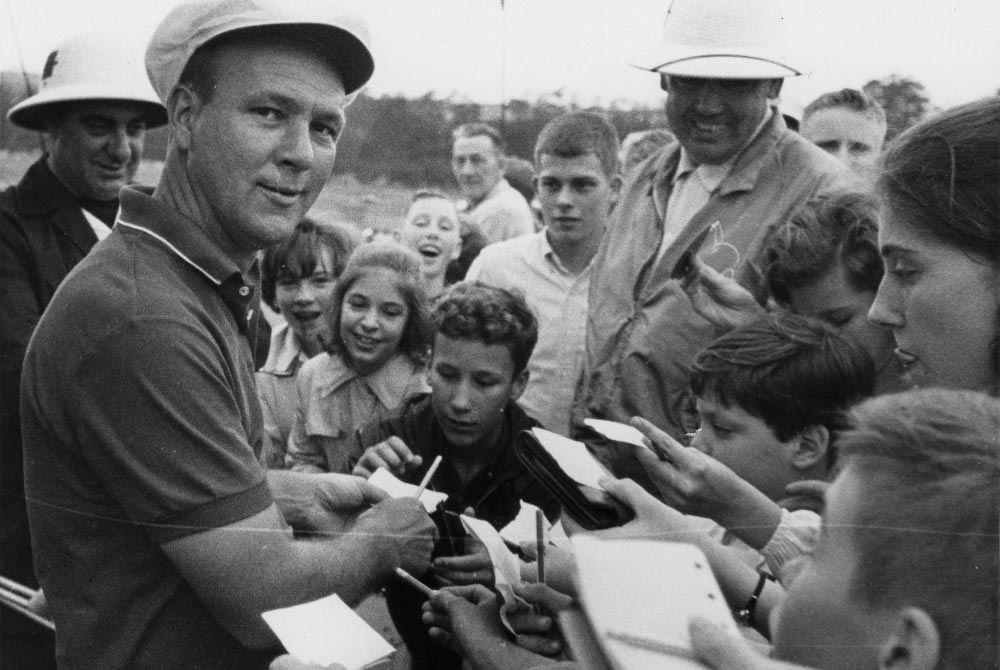

Palmer did not dwell on his defeat for long though, and in hindsight it perhaps proved to be one of the greatest weeks of his life—the week that his adoring throng of followers was rebranded as Arnie’s Army.

“As he always did in those days, Clifford Roberts [Augusta National’s co-founder, with Jones] used GIs from nearby Camp Gordon [now Fort Gordon], the military installation where he [Roberts] spent two years as a young soldier, to work the scoreboards,” Palmer recalled.

“Many people don’t realize that the Masters was not a sellout in those early years. Anybody with five dollars could walk up to the gates and buy a ticket for the day. Cliff wanted as large a gallery as he could get that year since the Masters was being televised for the second time, so he gave free passes to any soldier who showed up in uniform.

“The soldiers did not necessarily know a lot about golf, but when they found out I was defending champion they joined my gallery. That prompted one of the GIs working a back-nine scoreboard to announce the arrival of ‘Arnie’s Army,’ which is what it looked like. I can’t remember another time, other than my stint in the Coast Guard, when so many uniformed soldiers surrounded me. A year later, when I won my second Masters title, I thanked the ‘army’ of supporters who came out to follow me.

“Meanwhile, Johnny Hendricks, a reporter from The Augusta Chronicle, picked up on the phrase and ran the headline ‘Arnie’s Army’ for the first time. Boy, did it ever stick! Before I finished my playing career, I think every newspaper, magazine or television station that covered golf used the phrase at least once.”

Palmer’s second Masters victory, in 1960, coincided with the rise of television in suburban America, and he had become golf’s first “superstar.”

After three rounds he led by one stroke from Hogan, Julius Boros, Dow Finsterwald, Venturi and Billy Casper. With two holes remaining, it looked as though Venturi, the only member of the chasing pack who had not already won a major, was about to break through. But Palmer thwarted him again with birdies at 17 and 18, holing out from 30 feet and 6 feet respectively, to claim his second Green Jacket.

A third was dramatically ripped from Palmer’s shoulders 12 months later when, needing a four on 18 for victory, he contrived to take six and hand the title to Gary Player. After trailing the young South African by four after three rounds, he had worked his way into the lead and stood in the middle of the final fairway with a one-shot lead.

But before playing his approach Palmer allowed himself to be distracted and prematurely congratulated by an old friend, George Low, in the gallery. “Nice going, boy, you won it,” Low said. With those words ringing in his ears and his concentration blurred, Palmer pushed his second shot into a greenside trap, splashed out over the putting surface and took three more to get down. Thus Player was gifted his first Masters title and the King was deposed—into a tie for second with the amateur Charles Coe.

Palmer was steaming, although his fury was directed entirely at himself. “What really tore me up inside was the knowledge that I’d lost because I’d failed to do what Pap had always told me to do: stay focused until the job is finished,” he said.

After a year of recriminations, he exacted sweet revenge in 1962 by beating both Player and Finsterwald in the Masters’ first ever three-way playoff. But the playoff only became necessary because Palmer, who led Player by four and Finsterwald by two after 54 holes, suffered another final-round stumble. In fact, had he not chipped in for a two at 16—after being irked by a remark to air by on-course commentator Jimmy Demaret—and birdied 17 from 20 feet, Palmer would have been ruing yet another Augusta fumble.

After a modest start to the 18-hole playoff, which saw him trailing at the turn, Palmer then reeled off a blistering back nine of 31—eight shots better than his fourth-round effort—to seal his third Masters triumph.

“I admitted in the press-room afterward that I felt very fortunate to have won and really looked forward to a day when I might walk up the 18th hole with the tournament safely in hand, actually able to enjoy the experience of knowing I didn’t have to pull off another miracle shot to win,” Palmer said.

After a disappointing tie for ninth in 1963, the year Jack Nicklaus confirmed he was the real deal, Palmer’s wish came true in 1964.

Certainly, he felt it was his greatest victory. After months without winning on tour, Palmer had heard talk that his career was in eclipse. His answer was to play majestic golf and he led, in effect, from the first tee shot to the last putt—for a birdie, of course. He won by six strokes, and at the time his 276 total was the second best score in the tournament’s history. He also became the first man to win the Masters four times.

His plan of attack was perfectly executed, on a day-by-day basis. The experts predicted it would be a sluggers’ tournament with little roll on sodden fairways. The sluggers they had in mind were Palmer and Nicklaus, but by the end of the first round five men shared the lead on 69: Palmer, Player, Kel Nagle, Bob Goalby and Davis Love, Jr.

On the Friday, Palmer’s 68 was near flawless, one of his finest rounds. Partnered by Chi Chi Rodriguez who hammed up to the galleries, he resolved not to be distracted under any circumstances and led by four at halfway from Player, whose 72 included six one-putt pars, and by seven from Nicklaus who was struggling on the greens.

Saturday was the day of pursuit with everyone chasing Palmer. Eschewing his customary tendency to throw a few shots away early on to make things interesting, he ground out a “take every shot as it comes” third round of 69 that as good as slammed the door shut in the face of his rivals. He stood 10-under-par for the tournament after 54 holes and his nearest challenger, five strokes back, was young Australian Bruce Devlin.

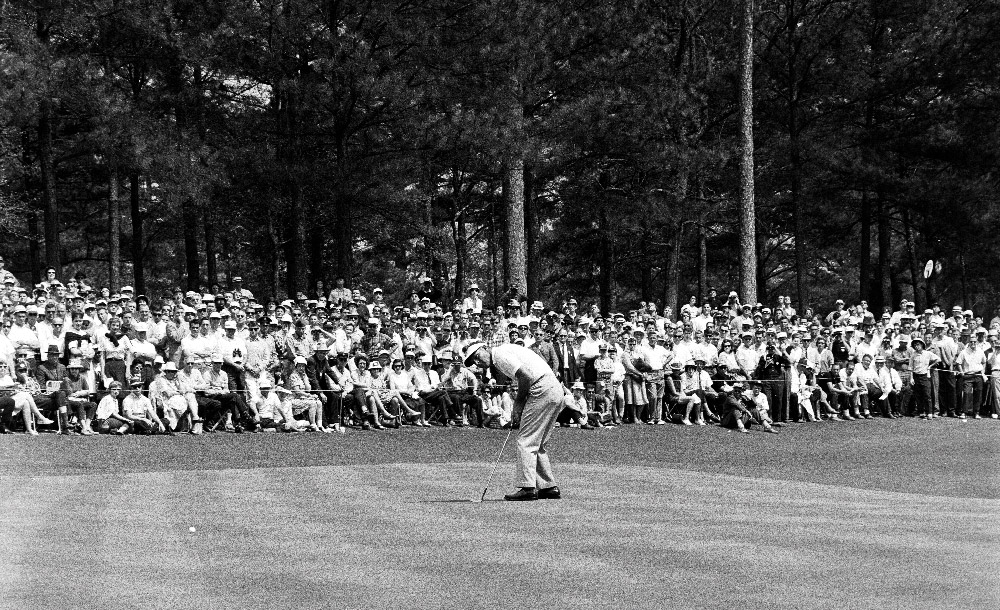

Twenty-four hours later, Palmer was able to stride up the 18th fairway and soak in the appreciation and affection from the Masters patrons that cascaded from all around. Then he sank the 25ft birdie putt on 18 and signed for a closing 70, having seen off dynamic late charges from playing partner Dave Marr, who seemingly holed every putt he looked at on the front nine, and Nicklaus.

On the 18th tee, Palmer asked Marr, who at that point was third, trailing Nicklaus by one: “What can I do to help you?” “Shoot a 12!” Marr quipped, though in the end he needed no help from Palmer as he sank a downhill 30ft birdie putt on the 18th green to tie the Golden Bear for second place.

“At the start of the tournament,” Palmer said afterwards, “I told all the reporters what score I thought would win, somewhere between 276 and 278, and I tried to set that as my point of aim. I played here as I would like to be able to play in every tournament. When I got here I felt as great as I have in years.”

For once, during that memorable week, there was no spluttering down the stretch and the future seemed rosy again.

Strangely, though, that was it for Palmer in terms of major wins. He claimed a further 19 PGA Tour titles, not to mention numerous international wins, but his majors tally parked at seven and went no further. There were many subsequent near misses, including three top-four finishes in the next three Masters, but his race for the Green Jacket was run.

In total, Palmer played exactly 50 times in the Masters and served as honorary starter from 2007 to 2016, in recent years with his fellow “Big Three” rivals, Player and Nicklaus.

Palmer’s reign over golf ultimately stretched beyond 60 years and will long continue to bequeath its legacy wherever the game is played and loved. Augusta National is not only one such place, but where many of the most vivid chapters of Palmer’s epic story unfolded.

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |