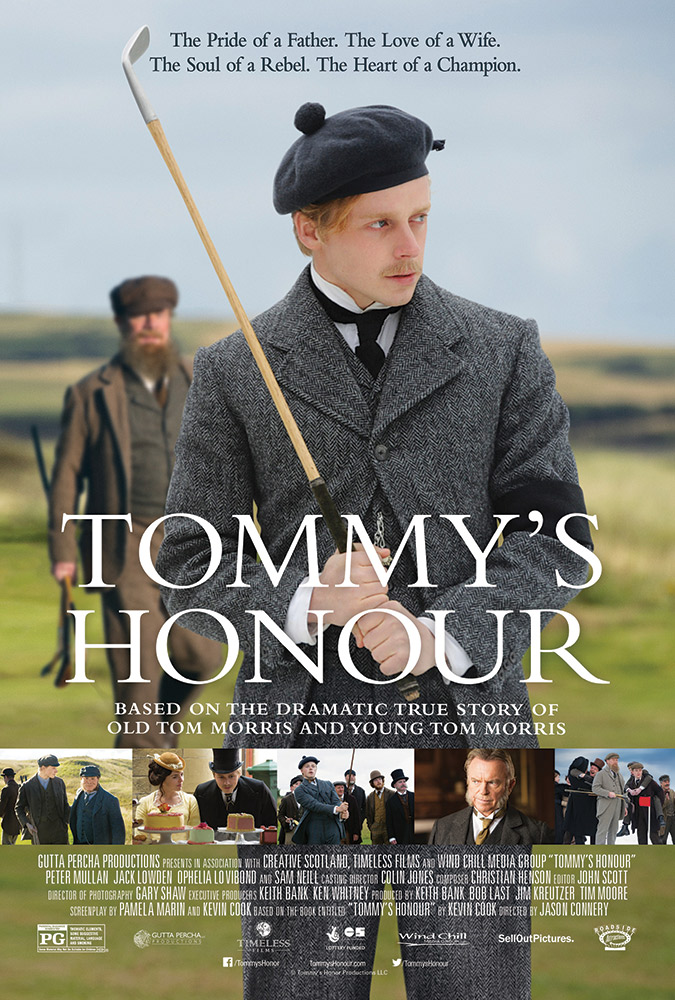

Why golf movies matter, and why Tommy’s Honour might be the best one ever made

In the winter of 1895, Louis and Auguste Lumière set up their new movie machine, a cinematograph of their own design, and made history. The brothers’ compilation of short scenes from everyday French life, shown to a paying audience in a Parisian café three days after Christmas, marked the debut of commercial cinema, as it was the first film ever shown for money.

In Scotland some months earlier, over two nights at the St Andrews Town Hall, another dramatic debut of sorts took place when Old Tom Morris, then 74 and still Keeper of the Green at golf’s ancestral home, appeared in his first, and likely his only, theater production. Standing on stage in front of a backdrop painted to resemble a links course, Morris played himself in a three-scene show that concluded with him missing a short putt to lose a match to a man in a scarlet jacket, presumably like those of the St Andrews membership. Recounted in 1907’s The Life of Tom Morris, it was an ignoble role for the man who, with his son Tommy, had done so much for golf and who had one of the most compelling personal stories ever told—if not seen, exactly. Not until now, that is.

Tommy’s Honour is a new film about the Toms Morris, and if you read no further know that this magazine considers it a “must watch” for any fan of the game. Based on the 2007 book by Kevin Cook, Tommy’s Honor: The Story of Old Tom Morris and Young Tom Morris (Cook also wrote the screenplay with wife Pamela Marin), the movie was shot last year and sees its international release this spring. It’s a good golf film, perhaps the best, and good golf films are hard to make. They must be, considering there are so few. More than that, the film is important, and here’s why:

Between the birth of commercial cinema in 1895 and this year’s release of Tommy’s Honour, Wikipedia counts just 37 golf films (and that includes a Woody Woodpecker cartoon). Wikipedia missed 2014’s Seve the Movie and a few others, but compare it to the site’s 39 films about chess, 46 about hockey and 266 about boxing, and you’re left wondering how many foursomes meet each week for a Sunday punch-up. It’s even more astounding considering that golf has its own network, the Golf Channel, which reaches more than 200 million homes in 84 countries and 11 languages. And yet 37 films in 122 years.

In a 1985 essay “Cinema & Culture,” University of Iowa professor Dudley Andrew wrote, “as satisfying as is the metaphor of movie screen as cultural mirror, the power of the camera to set the scene of culture is a power much stronger than that of mere reflection. The cinema literally contributes to a culture’s self-image, inflecting, not just capturing, daily experience.”

Applied to the culture of a game currently experiencing a decline, one might take this to mean that we could use a few more good golf movies. Let’s see what we’ve had so far:

Golf has played memorable bit parts (The Thomas Crown Affair, Goldfinger), it has been a supporting cast member (Pat & Mike, Banning) and it has been the star of the show (The Greatest Game Ever Played). It was a popular subject in the early 20th century, appearing in silent movies like the simply titled Golf in 1922, from Oliver Hardy of Laurel & Hardy fame, and Spring Fever in 1927, based on a 1925 musical and featuring a young Joan Crawford. The sport had a good run in 1930, a year that saw The Golf Specialist (W.C. Fields’ first “talkie”); Part Time Wife (in which a golf-mad woman leaves her husband at home); Love in the Rough, a talking version of Spring Fever; and Follow Thru, one of the first movies filmed entirely in Technicolor.

Golf on screen tends to succeed when it’s funny, evident in early films by The Three Stooges (Three Little Beers, 1935) and Our Gang (The Divot Diggers, 1936) and in modern films like Caddyshack (1980) and Happy Gilmore (1996). It also works when dressed as romantic comedy, as it was in many of the early productions and later in the 1996 Kevin Costner/Rene Russo film Tin Cup. And then there are the golf films that defy explanation (see sidebar: When Golf Gets Weird).

But it’s when things get serious that golf films tend to falter, when they get biographical or philosophical, and this is a shame because such projects often are founded in a real love for the game. Films like 2004’s Bobby Jones: Stroke of Genius, which Roger Ebert dubbed the “kind of movie you’re not surprised was financed by The Bobby Jones Film Company.” Or 2011’s From the Rough, which used too light a touch to tell the astounding story of Catana Sparks, the first woman ever to coach a college men’s golf team.

Follow the Sun did better with Ben Hogan in 1951, but the film avoided some complex but important points of accuracy.

On the philosophical side, Golf in the Kingdom and The Legend of Bagger Vance were based on novels that drew heavily from Eastern traditions, while films like Seven Days in Utopia and Birdie & Bogey followed Christian narratives to convey the more reflective “teaching” aspects of the game; but these and others of their kind rarely have worked, at least as far as we’re concerned.

And this brings us to Tommy’s Honour.

For anyone familiar with the story of the Morris father and son—Tom and Tommy, respectively—their importance to golf is undeniable. Old Tom, the greenskeeper and head pro at St Andrews from 1865 to 1903, was instrumental in founding The [British] Open and remains its oldest winner, taking the last of his four titles at the age of 46. The younger took four Open titles as well—consecutively. He’s still the only person to manage that, and still the youngest Open champ ever, at 17. Tom was also a lauded course designer, responsible for the now-iconic tracks at Prestwick, Muirfield, Machrihanish and others, and for innovations like top-dressing greens with sand to help with turf growth and with pushing club and ball design. Tommy was a kind of golf prodigy who effectively invented wedge shots and backspin, pushed for appearance fees and so much more. Off course, their lives (tragically short, in Tommy’s case) were the stuff of great drama, and the trouble with great drama is that what’s compelling in real life and on the page can manifest as farcical on the stage or screen. Given the melodrama inherent in the Morris family’s story, especially in Young Tom’s, and the breadth of the two men’s achievements in golf, this film could have been a fantastic mess. How happy were we, then, when it turned out to be just fantastic.

Much of the credit for that goes to director Jason Connery, who carefully steered the film past clichés that many, even subconsciously, might be expecting.

“You’ll notice there are no bagpipes, there are no sort of ‘oh laddie boy’ characters or dialog,” says Connery, speaking from his home in upstate New York. “Believe me, I had a number of fights with various people about, no, we’re not going to do heather in sunset swirling along in the wind, we’re not going to have a shot of the flag billowing. The beauty is in the background; if people notice it, then great.”

Rather, the characters are front and center, starting with Peter Mullan as the elder Morris and Jack Lowden as his son, and including Ophelia Lovibond as Young Tom’s wife and Sam Neill as St Andrews chief Alexander Boothby. All turn in solid performances supported by appropriate hair, makeup, costumes and set design, allowing viewers to inhabit the mid 1800s for just under two hours. Focusing on the people in the story, rather than leaning on the golf or on the setting for some clamant sense of importance, was key, Connery says.

“The thing that makes sport incredible, any sport, is the fact that it’s live. It’s absolutely impossible to know what will happen, so you sit there in anticipation of something happening. If nothing happens then it wasn’t particularly exciting, but if something amazing happens…

“A lot of the golf movies I saw, they tried to make the game the dramatic element of the film, and there’s all that hokum stuff: ‘Oh he sees the fairway different to everyone else, with piercing eyes looking down the fairway, the fairway becomes his world.’ Again, it’s not that it’s bad sentiment-wise, I think that it’s valid in its own way, but in such films it feels contrived somehow, it feels as though one is trying to push things.”

Toms Sr. and Jr. competed often, together and separately, and they’re often shown in competition during the movie. But while the outcome of many of the matches will be known beforehand, the playing sequences are a delight, invigorating even, and have more to do with the people on course than they do with the golf itself. We see almost nothing of Young Tommy’s first Open Championship victory in 1868, but watching his awkwardness afterwards as he’s being photographed with the trophy belt conveys both his youth and the excitement of the moment. Likewise, watching players and fans charge across the rough fairways as a pack, faces in the wind, shoving each other, patting backs, drinking and playing in what now would be considered ridiculous conditions, shows golf as it was born: wild, aggressive and fun. To see it thus is good for the game today, more often displayed as manicured, polished and safe.

Though it’s not the specific focus of any scene, the landscape does come into play, and seeing lauded tracks like St Andrews, Prestwick and North Berwick much as they would have appeared when they were new is thrilling. During a match at Musselburgh against longtime Morris rivals Willie and Mungo Park, details like the golfers pausing to allow racehorses to pass before continuing on (the racetrack cuts through the course) and Tommy having a quick nip from his flask as the gallery presses in behind the players, give you an idea of the starkness of golf at the time, certainly compared to today’s well-tailored game. Later, when a fist fight breaks out in a bunker between supporters of St Andrews and supporters of the home course, some of it begins to seem like a plot device—until you realize it actually happened, as Connery points out.

“We went to Musselburgh, it has a racetrack around it,” he recalls. “What was lovely was they didn’t cut the fairways or the rough for us for three weeks before we shot there.

I was using the rough as the fairways and the fairways as the greens. And the bunker that we shot the fight in was the bunker that they did have a fight in.”

In terms of accuracy, many of the locations, including St Andrews, couldn’t be used for filming given their current condition.

“What basically happened when I came over for the first location scout,” Connery explains, “we’d gone to St Andrews, met the guy from the R&A heritage society, talked about the course and this sort of thing… Looking at the course, it’s absolutely pristine, there’s not one blade of grass higher than another. In 1866 the way they cut the grass was with sheep, so it wasn’t like that. We started to realize that none of the courses the way they are now were going to work.”

The solution came in an undeveloped piece of land roughly 45 minutes from the Old Course, which was used as a stand-in when needed.

“There was cows**t everywhere and cows running around, but it was right by the sea,” Connery says. “Half of what you see is digital, the links road is all green-screen digital, which was fun in the windy weather. We built the 18th green and dug out the Swilcan Burn to build the bridge, coated it in fake snow at a certain point. What we managed to do, hopefully, was create courses that look like they were in the right place, but not overly ornate. I will confess that we tried to have sheep in a couple of scenes, but they kept running away—100 extras and 100 sheep, and the extras were much easier to control.”

Off course the film shows Tommy pushing back against many of the norms of the time, both in golf and in society, and experiencing absolutely horrendous moments of loss and pain, as he did in real life. Though many of the situations in which he and the other characters find themselves could easily have gone off the rails in terms of emotional displays, the actors’ restraint not only helps hold the film together but it also seems authentic.

“I was working with lovely actors,” Connery says, “and their abilities to not over-sentimentalize those moments was so important… And it was in the writing too. I’ve often seen, not just golf movies, this sort of thing where someone who has a view that’s different to our view at the moment, at this time, had to be a bad person. I didn’t want the upper-class people like [R&A chief] Boothby to be a bad person, I just wanted him to say, ‘What are you doing? That’s not how things are. We all know how things are.’

“Tom basically was never allowed in the R&A, and he was OK with that. He never went in the building. Ironically, there’s a great big cast of him on the side of the building and pictures of him hung inside, but he was never allowed inside. We chose in the film to have his son burst through to say things change, it’s a different generation. [Tommy] would have been the type of person who constantly would be saying ‘Why? Why do you accept that it’s like that?’ Every professional golfer—professional athlete—of today owes him a debt because he said well, everybody’s coming to see me, so why am I being paid a stipend? He challenged the established order, and it was so scary because the idea of turning to an upper-class guy and not giving him his due respect just because of who he was born to or whatever, you could get into real problems. When in the film Boothby says to Tommy, ‘In your father’s day you would have been whipped,’ he would have been.”

The camera work is logical, not distracting, the pace and length of the film are satisfying and the thought and consideration behind many of the decisions made by both the cast and crew are evident. As good as all of it is, none of it could have come together without the all-important financing. For that, it should come as some satisfaction to know that, more than any kind of investment (though it undoubtedly was), Tommy’s Honour was also a labor of love, perhaps especially for appropriately-named producer Keith Bank.

“I don’t do this for a living,” says Bank, who works as a venture capitalist. “I produced a movie 28 years ago and I swore I would never do it again.”

He made an exception for Tommy’s Honour, and he says it was down to the story.

“I spend 60 or 70 hours a week on this,” he explains, pointing out that in addition to raising funds for the film he’s also handling much of the marketing, promotion, distribution and other desk-side tasks associated with movie making. “It’s certainly not about the money. It’s more about my passion for the game and wanting to give back. It’s an amazing story, and I thought it just needed telling.”

Bank was in Scotland for work there and says that the attention to detail on the film is incredible. One example he gives is that oh-so-difficult bit for golf film actors to get right: the swing. For that, Bank says they turned to Jim Farmer, the R&A’s honorary professional.

“We were almost fortunate that [the actors]… really had never played before,” Bank explains. “We were starting with a blank slate. To swing hickories and hit gutta percha balls, it’s a longer, loopier swing. There’s more leg movement, they didn’t have any base to start with.”

Filming a promotional segment for the film, Bank says Jordan Spieth teed it up with a hickory club and a gutta percha ball and… “He hit it 70 yards dead right into the weeds,” Bank says. “It’s very challenging, this stuff. I thought both Jack and Peter did great. We had body doubles lined up with really good swings and we never had to use them, not one time. We knew we were going to get criticized regardless. People who didn’t realize that the swing was different back then were going to say it wasn’t right, and people who knew and saw a modern swing were going to say it wasn’t right for the period.”

But of course they did get quite a lot right. Tommy’s Honour took the 2016 British Academy Scotland Award (BAFTA Scotland) for Best Feature Film and Jack Lowden received a Best Actor BAFTA nomination for his work. The film has been up for other awards as well and reviews have been very good. But more than winning a prize or pleasing critics, the movie achieves something important simply by existing. In films, there’s nothing wrong with self-depricating comedy, hero worship or the odd bout of pretension, but if cinema really does impact a culture’s self-image, then this is a film that golf has needed for some time.

The story of Old Tom Morris and his son is a foundational story of the game, of the relationships that occur within it, its possibilities, its pitfalls, and the lines that golf can both draw and cross. A record of two exceptional lives and a movie that can reignite a love of the game—the real game, played in the elements with friends and banter—Tommy’s Honour is also a welcome addition to the catalog of golf films, one that will occupy a spot on the highest shelf in that collection for quite some time, we believe.

It was in 1866 that Old Tom Morris moved his home and business in St Andrews to a prime spot on The Links—the narrow road that flanks the 18th hole of the Old Course. His shop, “Tom Morris,” was not far from where the 18th green remains to this day. The shop has not budged either, and while it has changed hands a few times over the century since Morris died, the St Andrews Links Trust restored the “Tom Morris” shop in 2010.

While Morris’s trade was primarily golf balls and custom clubmaking and repairs, the Tom Morris brand today has taken his entrepreneurial spirit in a new direction, with premium men’s lifestyle collections of clothing and accessories; clothing inspired by the past, created for today and, like a Tom Morris golf club, built to last.

Find the Tom Morris collection at standrews.com/shop

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |