The very first U.S. Open to be staged at Pinehurst took place a mere 15 years ago. The winner, after an epic duel with Phil Mickelson, was the flamboyant and ebullient Payne Stewart. Four months later he was killed in an aircraft accident. Bob Harig recollects how joy turned to tragedy and salutes Stewart’s immortal legacy

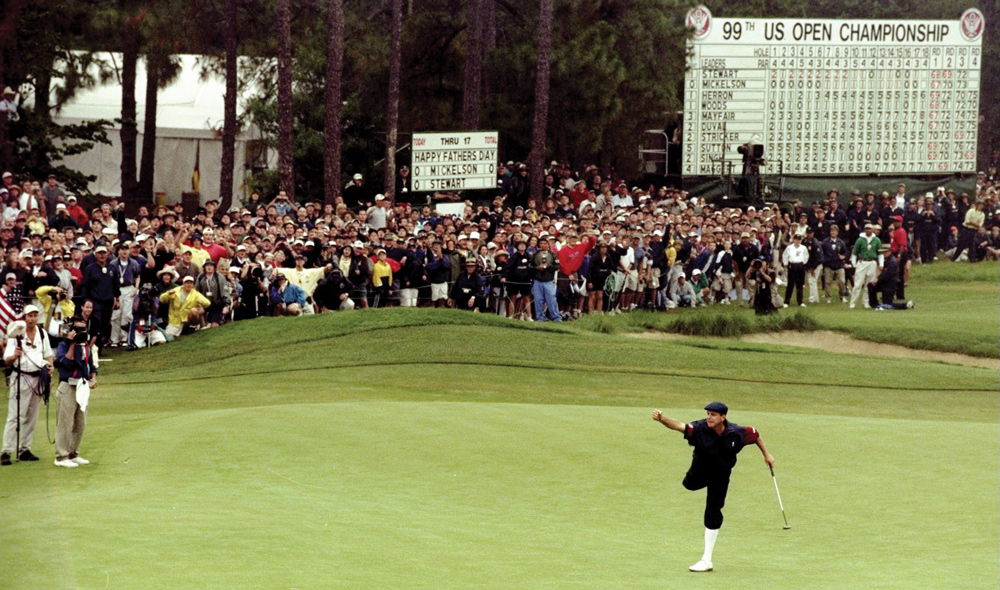

The enduring sequence of images will always be from the 18th green at Pinehurst No.2. The drama played out with Payne Stewart holing a clutch par putt, celebrating with an outstretched arm and leg, and then quickly extending his condolences to Phil Mickelson by relishing his rival’s impending fatherhood.

Mickelson’s wife, Amy, gave birth to the couple’s first child the following day, while Lefty’s first Major had to wait for five more years.

By draining that 15-footer, Stewart, the consummate showman, had claimed his second U.S. Open and third Major title. It was a dramatic conclusion to an amazing first U.S. Open at Pinehurst, and his feat is immortalized with a bronze statue commemorating the moment. The day will always be remembered—how could it not be? And this year, of course, the U.S. Open returned to Donald Ross’s hallowed North Carolina layout for a third time, 15 years after Stewart’s triumph.

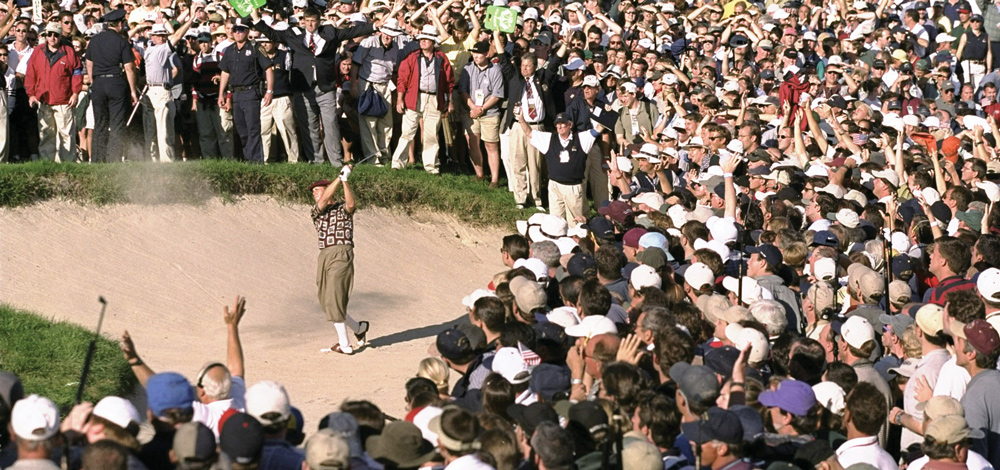

Colin Montgomerie remembers a far less publicized scene that involved Stewart, one that occurred just a few months after that U.S. Open victory. It took place at the 1999 Ryder Cup at Brookline, after the United States had clinched the competition and celebrations were already in overdrive. Montgomerie and Stewart were contesting the final singles match left on the course, and throughout the afternoon the Scotsman was forced to endure a shameful amount of heckling and abuse from American spectators.

On more than one occasion, Stewart tried to quell the noise in the crowd. And then, as they played the 18th hole tied, Stewart conceded the point with both players on the green, picking up Montgomerie’s ball, an act of sportsmanship often forgotten on an extremely tense and emotional day.

“It was a very difficult time, and the way he dealt with that situation I was in on the Sunday, with regard to his own performance, I’ll never forget,” Montgomerie said. “When he won the U.S. Open at Pinehurst, the first thing he said was he was in the Ryder Cup team, and he was thrilled to be in the Ryder Cup team—even more than he was winning the U.S. Open.

“He’d had enough, I’d had enough, and he picked my ball up at the last. I’ll never forget that.”

“It meant so much to him to represent his country. And to have drawn against me, of all people, in the singles match—I’m sure that it hurt his game, as well as it did my own. And it was a shame the way it finished. He’d had enough, I’d had enough, and he picked my ball up at the last. I’ll never forget that. Not all the memories [from Brookline] are fond. But that match I will always think of with fond memories, of that game with him.”

A month later, Stewart, just 42, passed away, killed when the private plane in which he was traveling to the Tour Championship lost cabin pressure and crashed in a South Dakota field. The golf world was stunned, and those who played with and against him, and watched him compete, find it hard to believe what happened even 15 years later.

Stewart had been denied victory a year earlier at The Olympic Club by a defiant Lee Janzen, and his Pinehurst victory showed there was some excellent golf left in his game. Who knows how many tournaments he might have added to his 11 PGA Tour titles, including those three Majors [the other two were the 1989 PGA Championship at Kemper Lakes and 1991 U.S. Open at Hazeltine]?

He had the kind of swing that could last, an old-style, easy-going move that appeared to be so effortless. Sure, he had his bouts of inconsistency, just like all golfers. There were highs and lows, periods of frustration and elation, but Stewart was about to enter a halcyon period in which he could play with the air of a champion with nothing to lose, or prove, and everything to gain.

It is impossible not to think what could have been. Surely there would have been more tournament victories. Maybe even another Major or two; and then a popular stint on the Champions Tour. Stewart would have turned 57 on January 30, and would have been completely at home strutting in those trademark plus-four knickers of his alongside all the other wrinklies.

“You could always tell when Payne was around. Life happened to Payne. He was the life of the party. There was always something going on with Payne.”

“That could have been the end of his Majors run, or it could have been the middle of it,” says long-time friend Peter Jacobsen, who played with fellow rock ’n’ roll fan Stewart in a band called Jake Trout and the Flounders. “[His game] was always unpredictable. He could pull a rabbit out of his hat at any time. This is something I don’t think you ever get over. You could always tell when Payne was around. Life happened to Payne. He was the life of the party. There was always something going on with Payne.”

And, of course, there would have been a U.S. Ryder Cup captaincy, probably around the time of 2006, when the Americans suffered one of their worst beatings at the K Club in Ireland. If not then, two years later for sure at Valhalla, when Stewart would have been 49.

“Obviously, we’d been through that whole day in June with him at Pinehurst and then the Ryder Cup at Brookline,” said Jim “Bones” Mackay, Mickelson’s longtime caddie. “I think the last time I laid eyes on him was at the party after the Ryder Cup at Brookline. He had an adult beverage in his hand and was as happy as a person could humanly be.”

No doubt, Stewart loved that Ryder Cup victory, loved being part of it. Undoubtedly, he would have loved to be part of other teams as vice-captain or captain.

The U.S. Open seemed to be a significant breakthrough for Stewart, almost a vindication. His longtime sports psychologist, Richard Coop, noticed a change in him, maybe the onset of maturity. Stewart won twice in 1999, his first victories since 1995.

The night before Stewart’s death, Coop spoke to him for 20 minutes. Stewart, known for his flashy attire—along with the plus-fours there was the tam-o’-shanter cap and two-toned shoes—was not always as assured as the image he portrayed. “He had a certain amount of peace that he’d never had consistently before,” Coop said. “At times, he got there. On the outside, he was cocky, confident. But on the inside, he was not nearly as confident. That’s the first thing I said to him [after winning the U.S. Open], it’s really hard to deny this one. I saw in the weeks between the time he won the Open and that day in October that he was much more mature, much more mentally at peace. We were talking about getting together in the offseason. He had a plan for 2000.”

As it happened, 2000 was the year the PGA Tour launched the Payne Stewart Award for players who show respect for the game, and especially its traditions of generously supporting charity and making a difference to the lives of others. Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Byron Nelson were its first recipients.

Supported from the start by energy supplier Southern Company, the award has been presented annually ever since. Other winners include Tom Watson (2003), Gary Player (2006) Davis Love III (2008) and Jacobsen (2013).

Nearly 15 years have elapsed since Stewart’s passing and much has changed. At the time, Tiger Woods had just won the second of his 14 Majors, David Duval was the world No.1 and Rory McIlroy was 10 years of age.

Then there was Mickelson, who played the entire tournament carrying a beeper (anyone have those anymore?), ready to leave at a moment’s notice if Amy went into labor. Stewart made the par-saving putt on the final green, but what if he hadn’t? Would Mickelson have been summoned away from a playoff the next day?

Daughter Amanda was born on that Monday. As agonizing as the defeat was, Mickelson has always looked back on it with perspective. “I just felt going into the ’99 U.S. Open that to travel all the way across the country when we were so close to delivering our first child, I felt very determined to make that worthwhile and to get a win out of it,” Mickelson said. “It was really a shock when that did not happen. Granted, it was the way it was supposed to be… but at the time I really was surprised because I was playing well and I was very determined to win and just didn’t do it.”

Mickelson has yet to win the U.S. Open, that championship at Pinehurst being the second of a record six runners-up finishes in pursuit of his national title.

With his return to Pinehurst in June, he once again missed the chance to complete a career Grand Slam, which would have been the perfect present to give himself on his 44th birthday, the day after the final round. To this day, Tiger Woods and Vijay Singh also look back on 1999 as a tournament they could have won. They tied for third, two shots back. It was a memorable finish, as Stewart also saved par on 16 before birdying the 17th to take a one-stroke lead before knocking home the immortal closing putt.

“I remember thinking, ‘That can’t go in,’” said Stewart’s longtime friend, Paul Azinger, who delivered a stirring eulogy at his memorial service. “You can’t make that putt to win the U.S. Open, but he did. He secured his legacy.”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |