The legacy of President Franklin D. Roosevelt includes the Works Progress Administration, that helped to lift the United States out of the Great Depression. As Dave Shedloski writes, the WPA also added a new dimension to majors golf at Bethpage State Park

Golf in the United States has realized several periods of robust growth but the game’s historians can readily point to two of the most consequential eras that inspired the masses to take up the game.

The first golf boom followed one of the most heralded upsets in championship history; Francis Ouimet’s stunning playoff victory over Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in the 1913 U.S. Open at The Country Club in Brookline, Mass. The second followed in the late 1950s and ’60s, when Arnold Palmer and the advent of television perfectly conjoined to bring golf to the everyman with a new sense of glamor. It didn’t hurt that during Palmer’s rise there was a man in the White House, Dwight Eisenhower, who was so enthralled with the game that he practiced on the East Lawn and unashamedly left spike marks in the wood flooring of the Oval Office.

But another U.S. President—Franklin Delano Roosevelt—was in fact a bigger promoter of the game and was responsible for making golf accessible to American citizens in more impactful and far-reaching measures. Roosevelt instigated a hugely significant period of growth for the game—after Ouimet and before Palmer—which in fact helped to drag the country out of the Great Depression.

Unlike William Taft, Woodrow Wilson or Warren Harding before him, Roosevelt showed no personal interest in golf while in office, even though he was a superb player before he contracted polio at the age of 39. “Golf was the game [he] enjoyed above all others,” his wife, Eleanor, once said. “After he was stricken with polio, the one word that he never said again was ‘golf.’” Nevertheless, he understood its allure as a challenging game and recognized its healthful benefits.

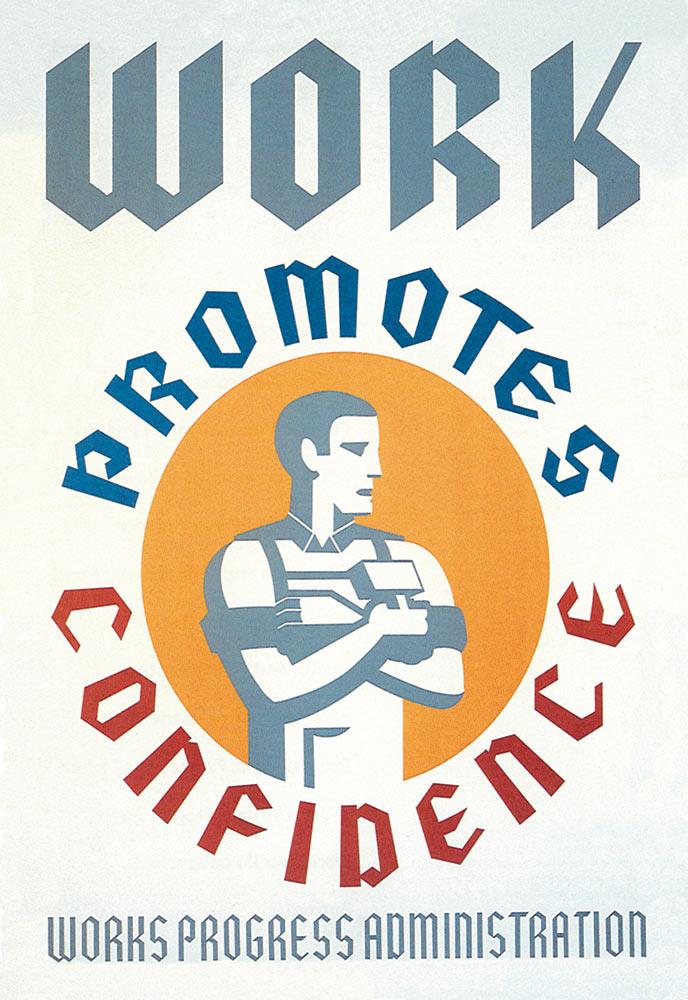

Which is why, when the Works Progress Administration was created in 1935, golf received a healthy injection of government funds. The WPA was arguably one of the most ambitious and important creations in the New Deal, a series of programs initiated by the Roosevelt administration in response to the Great Depression. (The Social Security Administration is the most well-known, enduring and consequential legacy of that era.)

Financed to the tune of $4.9 billion just in its first year, the WPA sought to employ the hundreds of thousands of American citizens out of work by tackling a myriad of infrastructure projects including roads, bridges, schools, hospitals and post offices. But it also hoped to improve the daily lives of Americans by contributing an array of recreational and leisure facilities such as playgrounds, tennis courts, zoos, botanical gardens, gyms, baseball fields and, yes, golf courses. The belief was that recreation enhanced public well-being, both physically and psychologically, which was hugely important during that trying era.

From Maine to California and Oregon to Florida, golf courses were either being built or upgraded, which kept busy course architects like Donald Ross, Perry Maxwell, Robert Trent Jones and A.W. Tillinghast, even if it was at cut-rate fees. (Ross was believed to have bid on projects for 10 percent of what he charged prior to the Depression.)

According to an Associated Press wire story from early 1936, the WPA announced that it intended to finance the building or improvement of 600 courses, and it already had begun work on 306 courses at a cost of nearly $10 million. Bobby Jones praised the work of the WPA and offered to consult on the creation of the courses, the vast majority of which were municipal layouts. A few years earlier Jones got his feet wet on course design working alongside Alister Mackenzie on building his private masterpiece, Augusta National in Georgia. “I had no idea their program was so extensive,” Jones was quoted as saying in an April news story. “It will help to bring the game within reach of people who want to play but can’t afford membership in private clubs… I’ll be glad to give them suggestions to help the program.”

Golf course designer and historian Dr. Michael Hurdzan said the WPA and the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), which helped man a lot of the projects, were not just instrumental in making golf more available, but also in offsetting the loss of other courses, mostly private.

“Not much talked about is that the number of golf courses in the U.S. plummeted between 1929 and 1945,” Hurdzan said. “Some went under, some were converted for agriculture or a wartime need. So the WPA was hugely important for the game—and not just in that era. The benefits are still felt today in a lot of parts of the country.”

According to another AP story dated December 17, 1936, of all the projects undertaken by the WPA, the largest by far was Bethpage State Park, situated on 1,368 acres in Farmingdale, New York, on Long Island. Four courses were eventually built, the last of them being the best and toughest; the Black Course, which opened on May 30, 1936. When the Blue Course hosted the U.S. Amateur Public Links Championship that fall, first-round losers were given the chance to compete in a consolation event on the Black Course. A Brooklyn reporter observed that it wasn’t much of a consolation because “the Black Course is one of the world’s toughest golf courses, not shaded in the least by Timber Point, Shinnecock Hills or Pine Valley.”

The reputation of the Black Course is no less formidable today. When it welcomes the 101st PGA Championship, May 16-19, the Black will host its third major championship after the 2002 and 2009 U.S. Opens, won, respectively, by Tiger Woods and Lucas Glover. In 2024, it will welcome the might of the Ryder Cup.

This year’s PGA, it should be noted, is being staged in a month other than August for only the third time since 1969. The exceptions were in 1971, when it went to PGA National in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, in February, and 2016 when it was contested in July to accommodate golf’s inclusion in the Olympics. With the Masters, U.S. Open and British Open all cemented in their respective slots in April, June and July, the PGA’s move to May fills a logical gap.

With its rolling terrain, elevated greens, large and deep bunkers, tall fescue native areas and a collection of long par-4s, the Black Course is a demanding layout, so much so that a sign welcomes golfers to the first tee with: “WARNING: The Black Course is An Extremely Difficult Golf Course Which We Recommend Only For Highly Skilled Golfers.” Woods—who won the 2002 Open there at 3-under 277—called it, simply, “a brute”.

“There is no let-up, no place to hide,” said Rees Jones, who has twice renovated the Tillinghast masterpiece, which for recreational golfers plays to a par-71 with a course rating of 76.6 and a punishing slope of 148. It measured 7,438 yards and played to par-70 for the 2009 U.S. Open.

Bethpage, which also hosted a FedExCup Playoff event on the PGA Tour in 2012 and 2016, isn’t the only celebrated layout with WPA roots. Perry Maxwell designed Prairie Dunes Golf Club in Hutchison, Kansas, and Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1937. Brown Deer State Park in Milwaukee, which once hosted the Milwaukee Open, was another WPA creation, as was the renowned Mackenzie design, the Scarlet Course at Ohio State University Golf Club in Columbus, Ohio.

What made Bethpage such a standout project was its sheer size as well as the various attractions; hiking and riding trails, picnic areas, polo fields and tennis courts. But golf was the anchor to it all, as it remains.

Three centuries ago the land upon which Bethpage State Park sits was the property of three Native American tribes until English settler Thomas Powell purchased a 15-square-mile tract for all of 140 pounds sterling. Powell named the land Bethpage, inspired by the Bible. In the Book of St. Matthew in the New Testament, there is a passage that refers to drawing “nigh unto Jerusalem and were come to Bethpage, unto the Mount of Olives.”

What Powell started, Benjamin Franklin Yoakum refined. A railroad tycoon, he bought 1,300 acres of Powell’s original land purchase and developed it into a spacious estate that by 1923 included Lenox Hills Country Club. By the time of the 1929 stock market crash Yoakum had passed away and his heirs sold the land to the Bethpage Park Authority, part of the Long Island State Park Commission, in 1933 for $1 million. Robert Moses, a master builder and president of the commission, oversaw the transformation of the expansive property into a multi-use park.

Using Tillinghast’s expertise and the Works Progress Administration that gave him more than 2000 workers, Moses brought four courses on line—the Green (formerly Lenox Hills), Blue, Red and Black. Greens fees for any of the four courses were $1 on weekdays, $2 weekends. A season pass good for weekday golf cost $15.

The Black Course was special from the beginning; Moses hailed it as “the People’s Country Club.” Rees Jones, who inherited the moniker of “Open Doctor” from his father, Robert Trent, said that Tillinghast was inspired by Pine Valley, which is still frequently ranked as the nation’s finest layout and this goes some way to explaining the difficult nature of Bethpage Black.

“The Black Course,” Jones said, “was quite clearly Tillinghast’s answer to Pine Valley in look and style of play. He was known to play there quite a bit. You see that especially with the bunkers. They are long, deep and massive, and they are pushed away from the greens, leaving long bunker shots, which are very difficult.”

The accompanying clubhouse also was built at the time with WPA funds and workers before a fifth course, the Yellow, designed by Alfred Tull, was added in 1958.

It’s ironic that the WPA’s contributions to golf intersected with the “Golden Age” of golf course design, the period from roughly 1910 to 1937 when many of America’s greatest golf courses were born. Among them were Pebble Beach, Oakmont, Cypress Point, Winged Foot, Oakland Hills and National Golf Links of America. Include Bethpage Black and Prairie Dunes in that mix.

With so many working-age men having gone off to fight in World War II or working in war production jobs, the WPA was discontinued in 1943 at Roosevelt’s recommendation. Operations in most states ended February 1, 1943 and the agency itself closed by the end of June. But the legacy of the WPA thrives, as golfers can well attest. Today, 300,000 rounds are played annually on the five layouts at Bethpage alone. As sports historian and author George B. Kirsch wrote, “For golfers, the cloud of this great economic crisis contained a silver lining.”

Follow Us On

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |